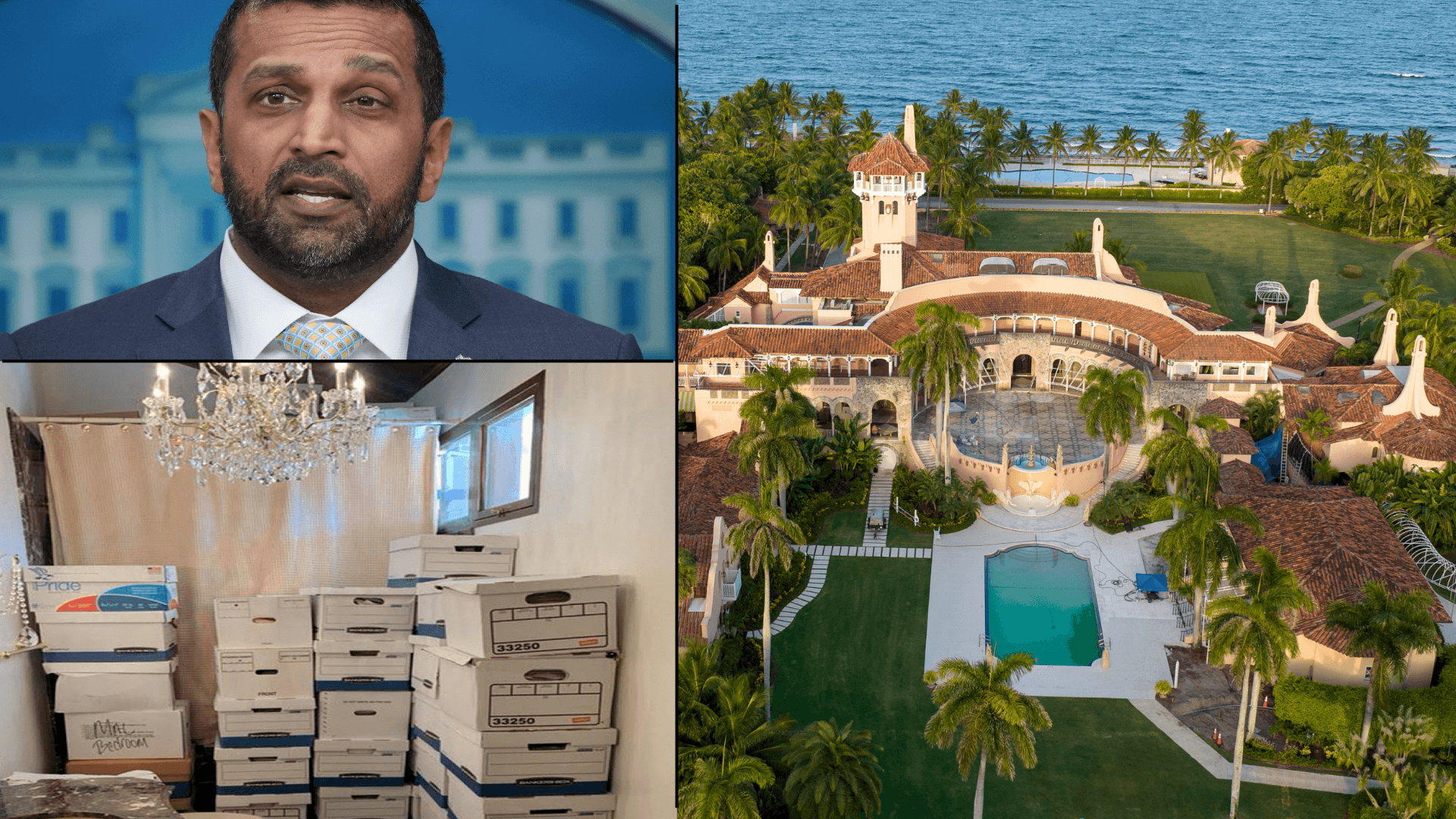

Exclusive: FBI Staffers Fired for Role in Mar-a-Lago Probe Were Assigned to Espionage Unit That Investigated Iranian Threats in America, Sources Say

By DANIEL EDWARD ROSEN

|‘Nobody wants the Americans to leave Korea,’ a retired diplomat says with 10 days to go before the election.

By DANIEL EDWARD ROSEN

|

By A.R. HOFFMAN

|

By HOLLIE McKAY

|

By LUKE FUNK

|

By A.R. HOFFMAN

|

By LUKE FUNK

|

By MATTHEW RICE

|

By MARIO NAVES

|Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.