Whatever the Color of Their Collars, Americans Love a Parade

The first Labor Day parade took place at New York City, with what the Sun described as a 12,000-strong ‘great parade of workingmen … marching with bright banners and emblazoned sentiments.’

Some leftists are using Labor Day to divide blue collars from white. This holiday, though, is an occasion to celebrate how Americans used the freedoms enshrined in the Constitution to “provide for the … general welfare” where other nations fell into bloody revolution.

The push for a “workingmen’s holiday” began in the Gilded Age of the late 1800s, high noon of the Industrial Revolution when the average American — including children — worked 12-hour days, seven days a week.

Mills, coal mines and factories were death traps in those days, and large-scale immigration meant employers could swap out employees like parts in a machine. Not satisfied to be mere cogs, workingmen and women began to form labor unions to advocate for their livelihoods.

This new identity inspired the secretary of the Central Labor Union, Matthew McGuire, to pitch an annual day of celebration, which led to the first Labor Day parade on September 5, 1882.

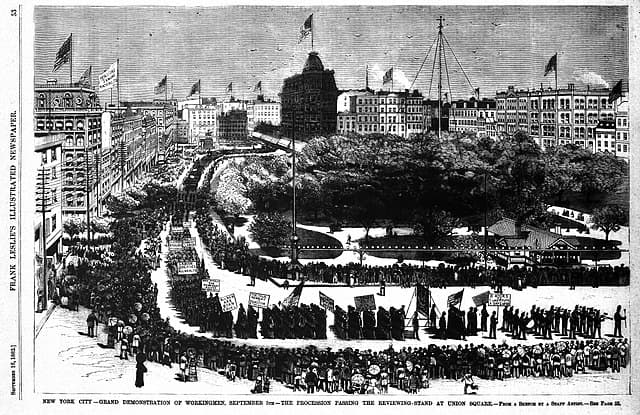

The tradition kicked off, as so many good things do, at New York City, with what the Sun described as a 12,000-strong “great parade of workingmen … marching with bright banners and emblazoned sentiments.”

They waved American flags and wore costumes as bands blasted out tunes. “The sidewalks were thronged,” the Sun reported of the two mile route from City Hall to Union Square, “with men, women and children, many of whom fell in behind and marched along.”

They had taken off work without pay for the festivities, but employers closed many businesses, too, in a show of unity. Bricklayers, clockmakers and others “stood shoulder to shoulder with the merchants, bankers, politicians, and lawyers” in the “oppressive heat.”

Throughout labor’s evolution, Americans feared its infiltration by communists, socialists, and anarchists on the left. Yet like those who marched in that first parade, violence was not a component of having their voices heard.

American values have always run deep in labor. The president of the AFL–CIO from 1979 to 1995, Lane Kirkland, led nationwide union support for Solidarity in Poland even over objections of the Carter administration which feared provoking Moscow’s communists.

Union support dropped during Kirkland’s tenure after its peak in the 1950s, but is now enjoying a renaissance, with a new Gallup poll finding support for unions at 64 percent, the highest level since 1965.

Thanks to our federalist system, the idea for Labor Day was able to start in one state and spread to others. In the 12 years following that first parade, 24 states made the first Monday in September the holiday’s fixed date, until it caught the eye of Congress.

Whereas other systems offered no such mechanism for reform, American citizens — many of them immigrants — had a raft of tools at their disposal.

Bloodshed was the exception rather than the rule in the campaign for safer conditions and fairer wages on the job. In 1894, for example, the American Railroad Union called a strike against the Pullman Palace Car Company in Chicago.

President Cleveland sent in troops, and more than a dozen strikers died in resulting riots. Unlike the way the Soviet Union tried to crush Solidarity, the federal government raced to make amends.

Cleveland knew the Democratic Party would suffer for his actions; so, to win back labor’s support, he signed legislation declaring Labor Day a holiday just days after the confrontation.

It applied to only federal employees but was a step to creating the nation we live in today. Although the 40-hour week itself didn’t become law until 1940, it wasn’t labor, but America’s greatest industrialist, Henry Ford, who gave the idea its biggest boost.

Ford gave employees in his factory something new — weekends — beginning at the dawn of the 20th Century. The move benefited his company, too, as leisure time began America’s love affair with the automobile.

The fortunes of unions will continue to rise and fall to maintain the balance between labor and capital, and each year we’ll pause to remember the men and women who make the nation work. Because whether we wear a blue collar or white, Americans all love our country — and we really love a parade.