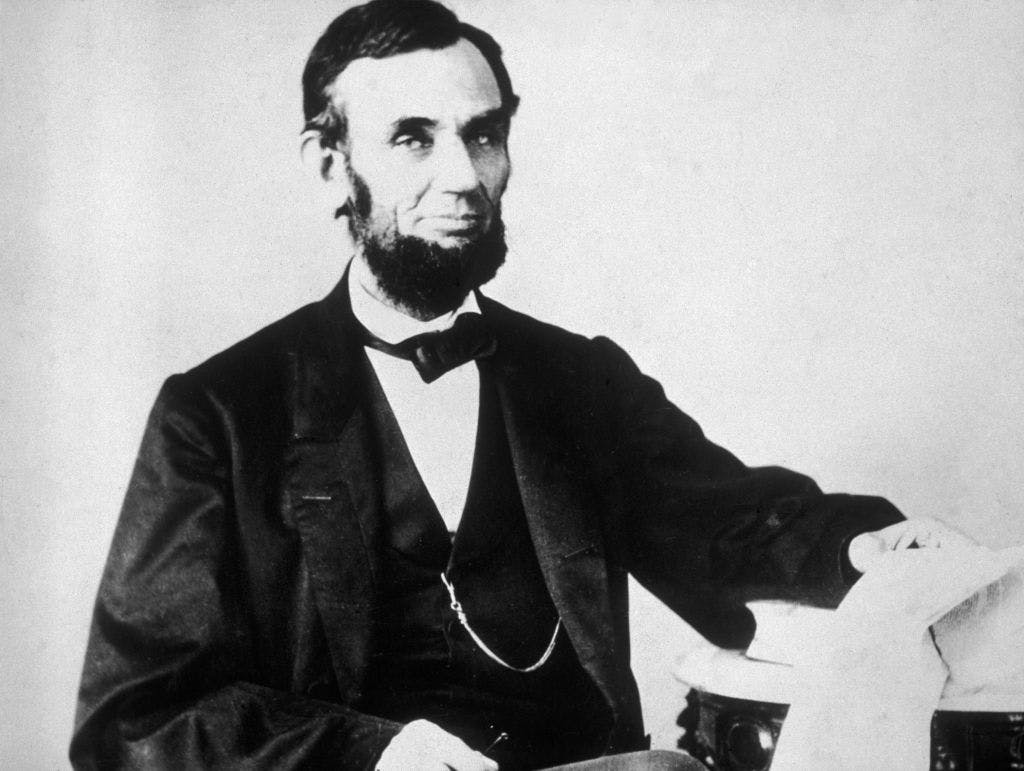

Lincoln Without Illusions, Tested in a ‘Time of Shadows’

Lincoln was a big man in every sense of the word and that he made Americans feel big, but the author does not hide his doubts about how well Lincoln would do in dispelling today’s shadows on democracy.

‘Our Ancient Faith: Lincoln, Democracy, and the American Experiment’

By Allen C. Guelzo

Knopf, 272 pages

For Americans, I suppose, democracy is an ancient faith, even if the history of the American polity runs less than 300 years. In an “Author’s Note,” Allen C. Guelzo calls this a “time of shadows” in which democracy is “shouted down in arrogance, and—all the more horribly—by those who have positioned themselves to reap its richest benefits.”

Mr. Guelzo, an esteemed Lincoln scholar, returns to his subject’s irrepressible democratic spirit when it was tested in another time of shadows. Lincoln’s biographer admires the way he spoke casually as he greeted friends and visitors to the White House, taking on all comers with an openness that shall be revisited when this book’s treatment of Lincoln and race is reviewed.

Lincoln loved electioneering, attuning himself to the voice of the people, yet he was no populist, no Jacksonian, but rather a Whig disciple of the Great Compromiser, Henry Clay. From Clay, Lincoln learned about the necessity of federalism, of balancing the powers of a central government and the states.

The rule of law, Lincoln argued, prevented a democracy from becoming a mobocracy that encouraged slaveholders to agitate for slavery in the western territories. He opposed Stephen Douglas’s advocacy of popular sovereignty, leaving the question of slavery up to the vote of the settlers — as a bogus ploy to seem democratic when in fact the doctrine subverted the rule of law.

Where slavery was already the law, Lincoln said he would not oppose it, even though he condemned slavery as immoral. He declared that as he would not want to be a slave, he had no right to enslave. And, he added, he had never heard of any man declaring a desire to become a slave.

Only the Civil War pushed Lincoln toward emancipation, and even then he temporized, Mr. Guelzo reminds us, freeing only those slaves who were in the rebellious states. Lincoln proceeded cautiously for political reasons, but also because he did not think that he had the legal authority to abolish slavery.

Lincoln can be accused of all sorts of contradictions, Mr. Guelzo concedes, but the president never became a dictator, and even seemingly dictatorial actions like the suspension of habeas corpus actually deprived few citizens of their rights and did not set a precedent followed by American governments after the war.

If Lincoln is the figure Mr. Guelzo recurs to, it is because he expresses the nation’s tensions, its virtues and vices — but vices he strove to overcome, as in the matter of race. Here’s the worst: Lincoln did not seem, as a policymaker, to believe in the equality of the races. He enjoyed minstrel shows and even imitated the crude behavior of minstrels.

Here’s the best: No black man ever met Lincoln who came away thinking he had been treated as an inferior. One-to-one, Lincoln simply could not act as another man’s superior, whatever his color. Frederick Douglass said after meeting with the president at the White House in 1863 “you have seen one gentleman receive another. … I tell you I felt big there.”

What is Mr. Guelzo telling us? That Lincoln was a big man in every sense of the word and that he made Americans feel big — not as victims, North or South, and not with the condescension that Douglass had often experienced among abolitionists whose radicalism was ostensibly far greater than Lincoln’s.

In a final chapter, Mr. Guelzo muses on how Lincoln would do in a modern media environment — this gawky man who had no charisma insofar as public performance goes. Would he have done a better job at Reconstruction than Andrew Johnson? Mr. Guelzo says perhaps, realizing that institutional opposition, even within Lincoln’s own administration, to his program of reconciliation with the South might well have stymied him.

Lincoln is a good example to follow, but Mr. Guelzo is under no illusions about the world now, and he does not hide his doubts about how well Lincoln would do in dispelling the shadows on democracy.

Mr. Rollyson is the author of “American Biography” and is working on “Making the American Presidency: How Biographers Shape History.”