Can Trump ‘Nationalize’ Elections?

By THE NEW YORK SUN

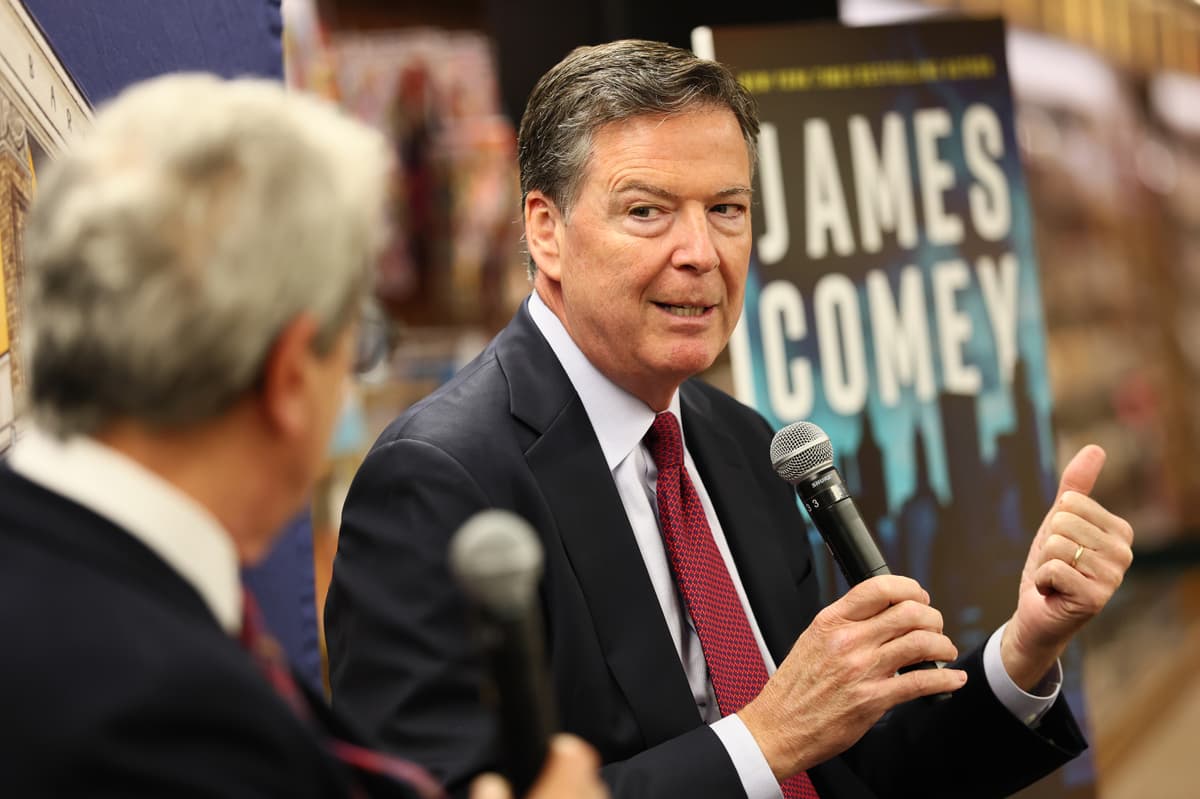

|The former FBI director is also requesting that the case be tossed because what he told Senator Ted Cruz in 2020 was ‘literally true.’

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|