Louise Bourgeois Gets Ready To Ditch the Canvas

Bourgeois is widely acclaimed as one of the vital sculptors of the 20th century, and her life of nearly a century resulted in a rich body of work. Her paintings can seem amateur by comparison, yet they also deliver clues about what is to come.

“Louise Bourgeois: Paintings,” which opened this week at the Metropolitan Museum, profiles an artist en route to her final vocation. Encompassing the years between 1938 and 1949 to a scale not seen in four decades, this exhibit demonstrates that artists do not spring forth fully formed. Their genius often requires gestation. Like a Silicon Valley founder, artists need to iterate before they triumph.

Bourgeois is widely acclaimed as one of the vital sculptors of the 20th century, and her life of nearly a century resulted in a rich body of work, of which the most famous are the strange and menacing spiders of all sizes she began building late in life, both stony and biomorphic at the same time. Her paintings can seem amateur by comparison, yet they also deliver clues about what is to come.

Many of these paintings feel inward, intimate, and curiously biographical, like a young artist who has to see herself clearly before attempting to represent the world. “Paintings” curator, Clare Davies, tells the Sun that Bourgeois began psychoanalysis after completing these works, but they seem touched by the Freudian uncanny, exposure that could have arrived via Bourgeois’s friendships with surrealists.

“Paintings” covers the crucial years of the 20th century, when Hitler rose and Europe fell and the world went to war. Yet a reasonable observer would be hard pressed to detect politics in these paintings. Bourgeois was in her own head, beginning with her early training in Paris to develop a way of looking at the world that would eventually find full expression in three dimensions rather than two.

Bourgeois describes these paintings as “architectural abstractions,” and there are structures littered throughout — door frames and towers, a swimming pool and something that looks almost like a gallows. They hang between abstraction and representation, fractions of a whole scene or story.

The artist studied mathematics and geometry at the Sorbonne, and this early work seems inflected by that training, as if she were trying to prove an elusive theorem or work out a knotty problem that the paint is not ready to name, one that concerns the buoyancy of objects and bodies through space.

In “Red Nights,” that suspension takes on a nightmarish hue as a woman, presumably Bourgeois herself, huddles in bed with her three sons, against a backdrop of swirling and cascading red. “The Runaway Girl,” the first thing visitors see in “Paintings,” feels more hopeful, with a girl decidedly striding through a band of blue and a swimmer in the background, perhaps uncertain of the destiny but sure of the impetus to continue.

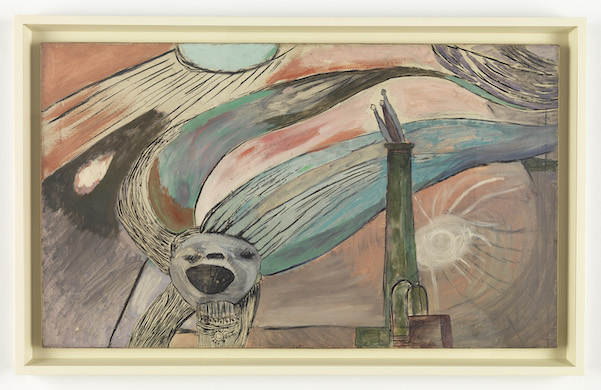

There are also girls, often altered or grotesque, floating against uncertain backgrounds, as if they were lost and looking for their parents to collect them out of the frame. “Untitled” features a vaguely human figure in the midst of an openmouthed scream, the painting swept with a kind of gale force. “Self-Portrait” centers a conventional figure in the foreground, but with a head exploded into simian hirsuteness.

Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: Christopher Burke

It is not only the self-directed gaze of the artist that kept Bourgois from meditating on the European situation. A quotation that adorns the wall of the exhibit describes how Bourgeois saw New York as a clean break with the past, a new chance at the moment when the axis of the art world was in the midst of an irrevocable shift to Gotham from the City of Light.

The quotation reads “Even though I am French, I cannot think of one of these pictures being painted in France. Every one of them is American, from New York. I love this city, its clear-cut look, its sky, its buildings, and its scientific, cruel, romantic quality.” It will be up to the viewer to concur or differ as to the New World quality of the paintings, but her assertion does make them feel more at home at the Met.

While the work as a whole is inchoate, there are bridges to Bourgeois’s fuller flowering, none so delightful as a surprising dagger. The tool appears in a painting, “No Swearing Allowed,” where it holds the center along with a nestlike object and then in one of the two sculptures the show includes, as if it flew out of the painting and adhered itself to Bourgeois’s future medium by way of magnetism or magic.

The most striking work is a series called “Femme Maison,” which Bourgeois completed between 1946 and 1947. They feature female bodies with the head replaced by domestic structures, including an offshoot of Bourgeois’s telltale hair, in an allegorical Frankenstein that plays on the French of both a female house and a housewife — the phrase means both house woman, and woman house.

“Roof Song” is a joyous riff on this overlapping of self and home, with a cheerful red brick house set against a blue sky streaked with a fluffy cloud. On the roof is a woman that reminds of an angel, presumably singing the song that supplies the painting’s title. One only hopes that she doesn’t jump, or soar away. Both seem equally plausible within the spatial logic of “Roof Song,” and for Bourgeois as well.

“Painting: Red on White” features a blue bouquet exploding out of a red vase, layered as if the flowers contained a whole world, a forest of azure pulling the painting skyward. Squint, though, and the bouquet starts to resemble a face, in outline if not detail. We don’t get the full Bourgeois in this show, but we do get the earliest peek of her, ready to ditch the canvas and linen for wood and stone.