Love in the Days Before Same-Sex Marriage

The biographer adds vital context with an epilogue in which he describes a union with his older male companion that his book’s subjects never dared to imagine possible.

‘A Union Like Ours: The Love Story of F.O. Matthiessen and Russell Cheney’

By Scott Bane

Bright Leaf, 288 pages

What biographer can claim to have enjoyed the kind of life that his thwarted subjects wanted for themselves? Scott Bane makes no such explicit declaration, yet in his epilogue he describes a union with his older male companion that his book’s subjects never dared to imagine possible.

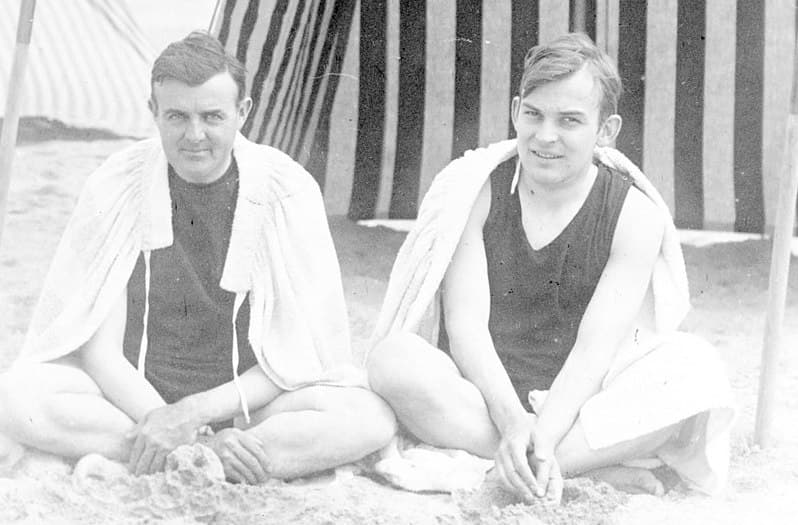

In January 1925, the literary historian/critic Matthiessen wrote to his painter partner Cheney: “We stand in the middle of an uncharted, uninhabited country. That there have been unions like ours is obvious, but we are unable to draw on their experience. We must create everything for ourselves.” The Harvard professor and his artist mate shared a home at Kittery, Maine, and so long as they did not openly appear as a gay couple, the community grew to accept, if not exactly to embrace them.

At Harvard, Matthiessen, author of the classic “American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman,” a pioneering contribution to what became American Studies programs, did not invite Cheney to campus events, and he did not mention him in dedications, even though Cheney’s painting had an important impact on Matthiessen’s understanding of art and literature.

Mr. Bane shows that while Matthiessen was determined to write about literary figures like Sarah Orne Jewett, one of those women in a Boston marriage similar to the one shared by Amy Lowell and Ada Russell, he could never openly discuss the homoerotic nature of writers like Whitman and Henry James.

Many scenes in this moving book illustrate how visitors to Kittery — T. S. Eliot, for one — tacitly accepted Matthiessen and Cheney as a couple but could never have done more than pretend the two men were simply friends who happened to share the same home.

That Matthiessen wished it could have been otherwise — that he may have wanted to marry Cheney, just as Mr. Bane married his partner — seems possible given that Matthiessen carefully preserved his love letters to Cheney.

When Cheney, nearly 20 years older than Matthiessen, died after suffering through many years of alcoholism that his partner made every effort to have treated, Matthiessen was bereft and for much of the time depressed, even as he continued to be productive as an author of several books while becoming engaged in radical politics.

If Cheney had been a worry, he had also been an inspiration — not only because of his art but because of an ebullient personality that had buoyed the workaholic Matthiessen, saving him from writing himself to exhaustion.

Disgusted with Harvard’s increasing Cold War conservatism under the leadership of James Bryant Conant, Matthiessen felt isolated, though he remained protected by a few close friends on the faculty. Toward the end of the 1940s, while working on a biography of Theodore Dreiser, Matthiessen became more strident in his pro-communist views, refusing to acknowledge the tyranny in the Soviet grip on Eastern Europe.

Perhaps if Cheney had lived longer, Matthiessen might have been able to relax, to brake himself. Without a partner, his depression worsened, and he took his life by jumping out of a 12th story hotel window.

Matthiessen had more than once contemplated such a death. The measure of his desperation can be gauged by the absence of a last paragraph in his Dreiser biography. He was so close to the finish and yet could think to do no more than end his own life.

Scott Bane conveys the torment of a defenestrated sensibility — in part by sharing in an epilogue some of what his own life has been like in a same-sex relationship that after 18 years became a marriage. Mr. Bane tells just enough of his own positive story as a contrast to the oppressive social and political conditions that contributed to, if not caused, Matthiessen’s suicide.

Even with these personal and intimate connections between the biographer and his subjects, Mr. Bane’s book does not neglect Cheney’s art and the kinds of books Matthiessen published, so that “A Union Like Ours” can be read as exemplary of the kind of biography worthy of “American Renaissance” — insisting that, when possible, knowing the situations and circumstances of writers’ and artists’ lives contributes vitally to both their aesthetic and historical significance.

Mr. Rollyson is the author of “Amy Lowell Among Her Contemporaries” and “Amy Lowell Anew: A Biography.”