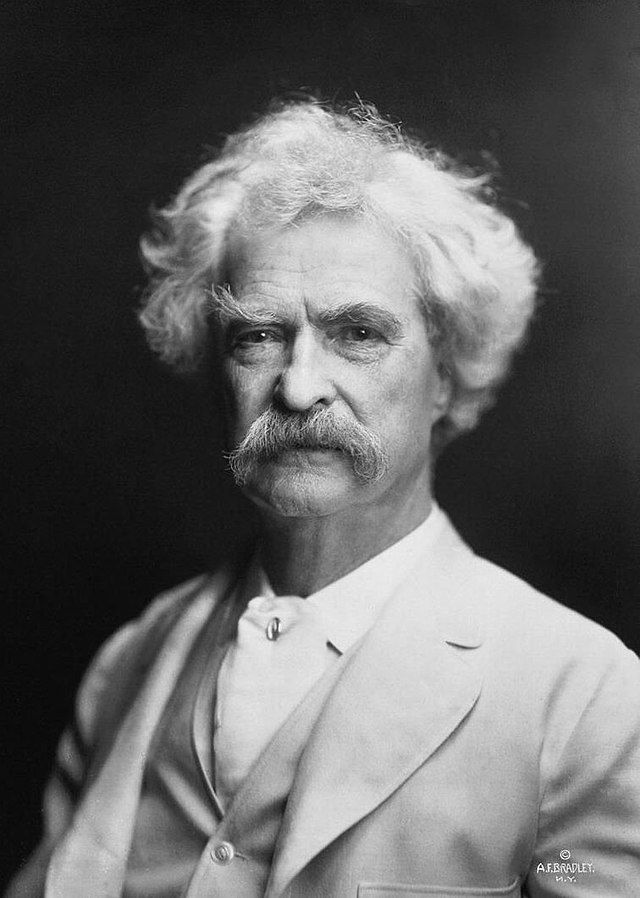

Mark Twain: The ‘Largest Literary Personality’

A new life of the author of ‘Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’ makes the case that he invented our celebrity culture.

‘Mark Twain ’

By Ron Chernow

Penguin Press, 1,200 Pages

Writing a biography of Mark Twain is a little like building a playpen for a lion. Soon enough the big cat will get loose. Biographer Ron Chernow’s 1,200-page “Mark Twain” is as sturdy a cage as can be conceived of — and yet this son of Missouri can hardly be contained. His voice tears through Mr. Chernow’s stately account, reminding readers why he is an incorrigible but unimprovable American original.

Mr. Chernow comes to Twain, born Samuel Clemens, after crafting celebrated lives of, among other worthies, Alexander Hamilton and Presidents Grant and Washington. Exhaustive does not begin to describe Mr. Chernow’s new work, which devotes hundreds of pages to the author’s largely catastrophic business ventures — Mr. Chernow brings the receipts — and tragic family life. The great comic outlived his wife and three of his daughters.

Readers who come to “Mark Twain” to get a sense of the literary acumen of the author of “Life on the Mississippi,” “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” and “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court” are liable to be disappointed. Mr. Chernow is more interested in Twain’s life than his art, and finds more grist in his letters and journals than in the fiction that has secured his reputation for more than a century.

Mr. Chernow, though, argues convincingly that Twain’s greatest fictional creation was his own persona. Much of Twain’s celebrity was manufactured on the lecture circuit, where the author was something like the Taylor Swift of his day — drawing crowds across the globe and performing with the resolve of an endurance athlete. Mr. Chernow judges that “no other American writer projected so vivid a personality when performing as Mark Twain.”

Twain, who honed his craft and developed what he called “dead sure tricks of the platform,” reflected that he “used to play with the pause as other children play with a toy.” His goal was to “vanquish the audience,” and, as with many performers, even his spontaneity was scripted. Another of Twain’s biographers, Justin Kaplan, writes that “it is hard to think of another writer so obsessed in his life and work by the lure, the rustle and chink and heft of money.”

The lecture tours did more than just provide an economic lifeline to Twain. Mr. Chernow explains how they elevated his profile from a frontier journalist at Virginia City, Nevada, to a figure with the “charisma and renown more often associated with politicians and star actors than authors.” He awed a young Winston Churchill though his relations with President Theodore Roosevelt, whom he called “the Tom Sawyer of the political world,” were frosty.

Twain’s barnstorming was always a matter of paying the bills. He not only wrote a book called “The Gilded Age” — he lived its ethos of boom and bust. The allure of being not just a scribbler but also a tycoon was a constant for Twain, who married a coal heiress and made plenty of money from his books and lectures. Twain, though, was reckless, sinking enormous sums into boondoggles like the Paige Compositor, which aimed to replace human typesetters.

Twain sunk some $8 million in today’s dollars into the machine, which never turned a profit. Mr. Chernow provides devastating detail on this folly and finds that Twain “had the worst possible temperament for business” because he was a “chronic worrier” who didn’t “worry enough about the things that mattered.” The biographer laments that the “most original character in American history” was an easy mark.

From Twain’s earliest days as a newspaper correspondent he mingled fact and fiction and honed a voice that was plainspoken, eloquent, and attuned to regional dialects, especially those of the South and West. Twain wrote that a “nation’s language is a very large matter” and that “there is no such thing as the Queen’s English. The property has passed into the hands of a joint stock company & we own the bulk of the shares.”

Twain’s politics form another strain of Mr. Chernow’s life. He evolved on race — his family owned slaves — to become one of the most eloquent defenders of African Americans. Mr. Chernow writes that “it’s hard to think of another white author of his era who felt so warmly toward Blacks or cared more about their plight.” Twain was also a fierce critic of the expanding American empire of the second half of the 19th century.

It is near impossible to find a Gentile writer — or a Gentile, period — who was as staunch a defender of the Jews as was Twain. He reflected that the “Jews have the best average brain of any people in the world” and amount to “the world’s aristocracy.” He called Jews a “marvelous race” and “the greatest people let loose.” He met Theodor Herzl, but worried that a Jewish state in Palestine would amount to a “concentration of the cunningest brains in the world.”

On balance, though, Twain emerges over the course of this long book as nothing less than a national treasure and, as Mr. Chernow puts it, the “largest literary personality that America has produced.” Mr. Chernow credits Twain with “anticipating today’s world of social analysts and influencers,” but the impression one gathers from this biography is of a man who could never put down his pen or still his mind. His stature can hardly be exaggerated.