MoMA Focuses on Fleischer Cartoons, and If It’s Disney You’re After, Keep Scrolling

The films became more virtuosic as they gained in popularity, with spectacular innovations in animation coupled with a sense of humor that was increasingly merciless, phantasmagorical, and ferocious.

‘Fleischer Cartoons: The Art and Inventions of Max Fleischer’

Museum of Modern Art

March 7-14

Observers of pop culture weary of the controversies surrounding Disney’s upcoming live-action remake of “Snow White” can seek some reprieve by going back to the source. No, not the studio’s full-length original “Snow White and the Seven Dwarves” (1937) or, for that matter, the fairy tale that was codified in print by the Brothers Grimm. I’m talking about “Snow-White” (1933), a seven-minute black-and-white cartoon featuring the inimitable Betty Boop.

Whether Boop can be considered a “girl boss” or any such paragon of umpteenth-generation feminism is a distinction I’ll leave to more enlightened minds to determine. Still, it should be noted that the creepoid scion of the patriarchy — you know, Prince Charming — is nowhere to be seen. Instead, this “Snow-White” is graced by the vocal talents of Cab Calloway, who sings the harrowing blues song “St. James Infirmary” in the guise of Betty’s pal, Koko the Clown.

“Snow-White” is one of six “greatest hits” that will be featured at the Museum of Modern Art on the opening night of “Fleischer Cartoons: The Art and Inventions of Max Fleischer.” It won’t be the only opportunity during the series that New Yorkers will get to enjoy Calloway’s music or, for that matter, his moves. “Minnie the Moocher” (1932) and “The Old Man on the Mountain” (1933) also feature Calloway, albeit reinvented through rotoscoping, a manner of animation involving the tracing of live action elements.

There is, then, an element of naturalism informing some of the most unnatural cartoons committed to film. Take “Snow-White,” in which Calloway is transformed into a ghostly figure with looping, elastic legs. The distortions of form are wild; their basis in the real, unimpeachable. The ultimate effect is unnerving. Chills can’t help but go up the spine upon watching this raucously over-the-top entertainment.

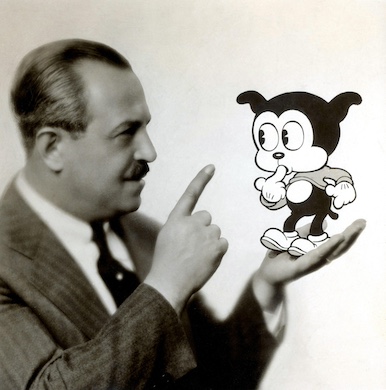

The rotoscope was invented by Max Fleischer, one of six children born to Jewish emigres who made their way to New York City from Kraków. An inveterate tinkerer, Max’s interest in new technologies corresponded with a gift for drawing: He was, for a time, staff cartoonist for the Brooklyn Eagle.

Max’s brother Dave had been working as a filmcutter at a film production and distribution concern, Pathé Exchange. A deal to make cartoons with Pathé fell through, so the brothers went on to work at Bray Studios, a concern headed by an old friend of Max’s, fellow cartoonist John Randolph Bray. The series of resulting short animated films collectively titled “Out of the Inkwell” would prove hugely influential. Their innovations and humor redound to this day.

“The Tantalizing Fly” (1919), among the earliest surviving Bray efforts, gives a good idea of the imaginative scope of the Fleischer Brothers. The picture opens with Max — not animated, but live action — at his drawing board and dipping his pen into the inkwell. As he attempts to draw a clown (in actuality, a rotoscoped Dave), a fly keeps alighting on the page. The resulting contretemps between the three protagonists forms a resolutely modern play on the metaphorical capabilities of illusion, in just under 4 minutes. The movie is dazzling in its virtuosity and very funny.

The films made by the Fleischers would become more virtuosic as they gained in popularity, with spectacular innovations in animation coupled with a sense of humor that was increasingly, to poach adjectives from MoMA’s curator, Dave Kehr, merciless, phantasmagorical, and ferocious. In other words, these ain’t Disney pictures, folks: they’re too manic, too surreal, and, according to some lights, profoundly Jewish.

Whatever else they might be, Fleischer Brothers cartoons are masterpieces of the artform. I’m sorry to report that the nine Superman cartoons Max and Dave put their hands to are nowhere in evidence, and that the adventures of Popeye are limited to a single outing, “Popeye the Sailor Meets Sindbad the Sailor” (1936). Still, this technicolor film is gorgeous, tuneful, and hilarious — indeed, a greatest hit. “Fleischer Cartoons” confirms that Max and Dave were, to quote Sindbad and Popeye, “most remarkable, extraordinary fella[s].”