Democrats Push Companies To Pass Tariff Refunds Along to Consumers, but Trump Administration Balks at Starting the Process

By LUKE FUNK

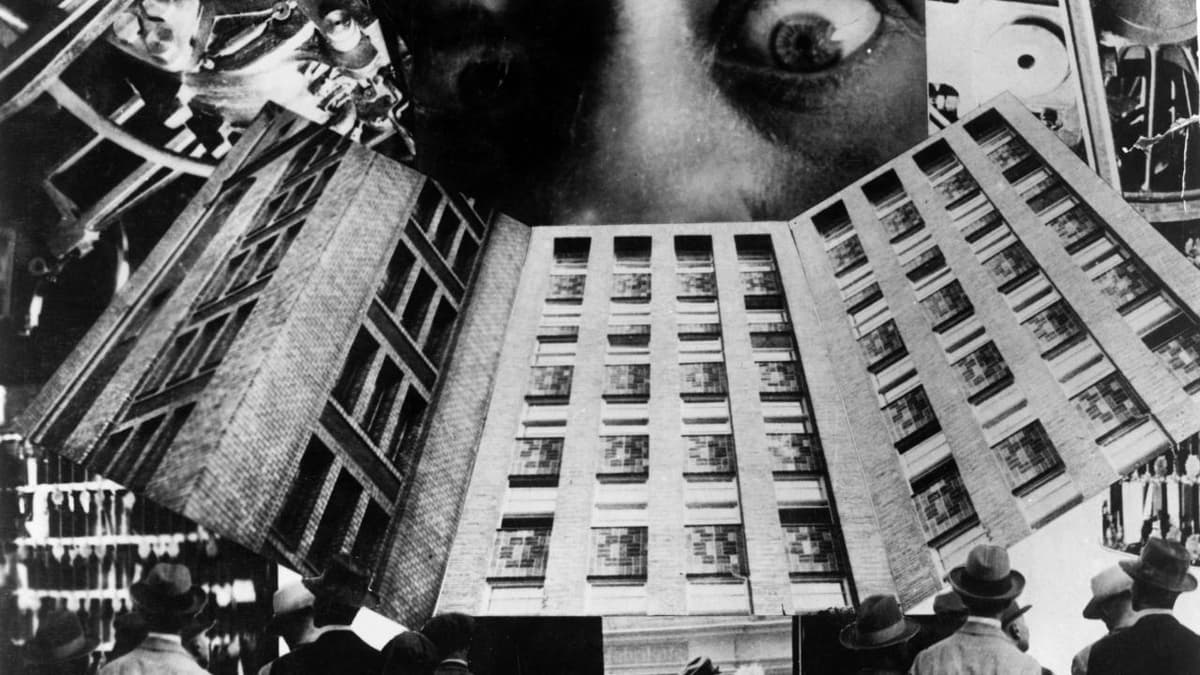

|Trained as a painter, Ruttmann brought the heady innovations of early Modernism into his cinematic efforts, including the scurried momentum of Futurist painting and the spooky sonorities of Surrealism.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By LUKE FUNK

|

By JOTAM CONFINO

|

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By M.L. NESTEL

|