Can Trump ‘Nationalize’ Elections?

By THE NEW YORK SUN

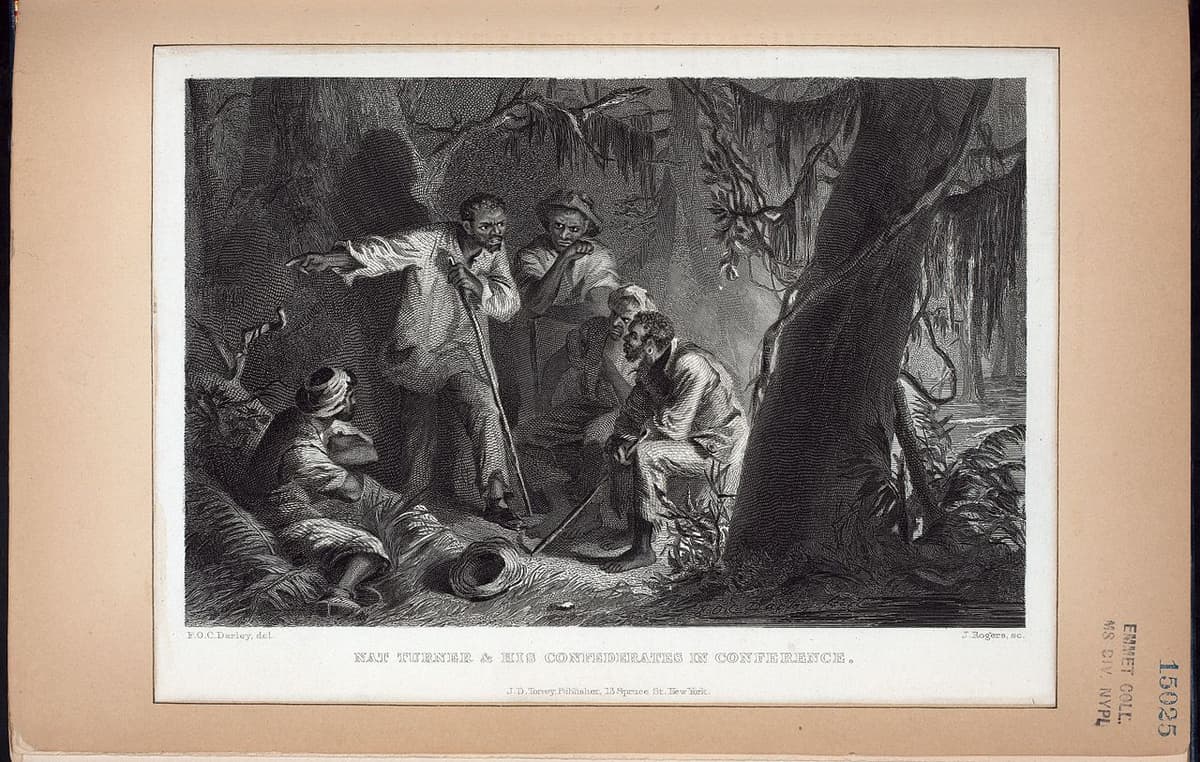

|The power of this ‘visionary history’ is its determination to re-create what Nat Turner experienced: apparitions of a white/Black conflict that he believed were divinely inspired.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|