Will Friday Diplomacy With the Islamic Republic Lead to a Military Strike?

By BENNY AVNI

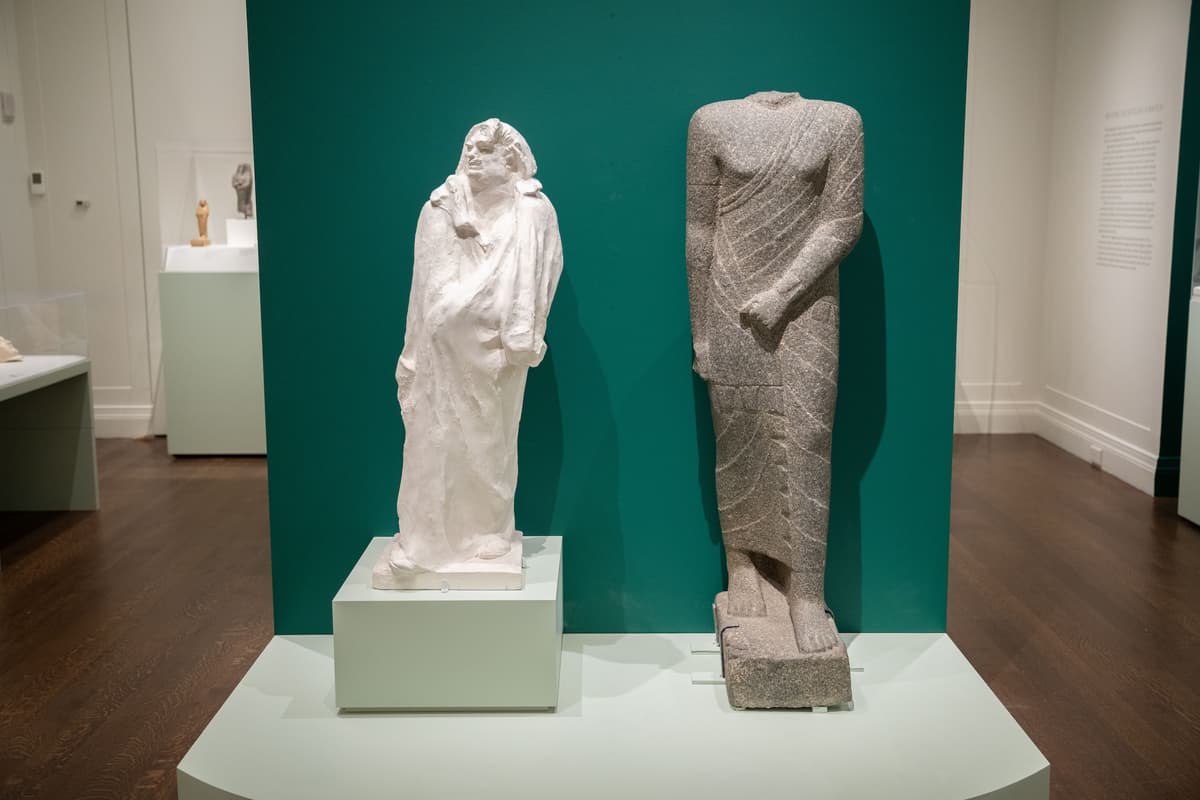

|‘Beyond anything,’ Rodin averred, ‘Egyptian art attracts me; it is pure. An elegance of spirit adorns all its works.’

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By BENNY AVNI

|

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|

By CARLOS SOUSA

|$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.