Poem of the Day: ‘And If I Did, What Then?’

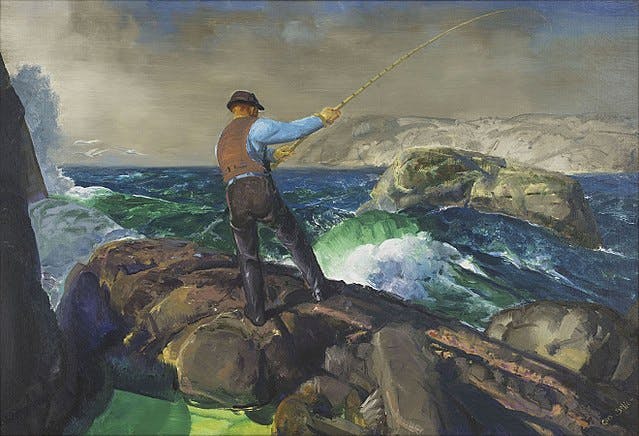

He who fishes long enough, waiting for a bite, will eventually outlast the luckier guys. He who has the sea to himself laughs last.

Today’s lighter Poem of the Day, by the early Elizabethan poet and playwright George Gascoigne (1535–1577), takes the form of a dialogue about sexual fidelity. In ballad-like stanzas, trimeter shifting to tetrameter in the third line, the poem’s speaker explains to his unfaithful mistress how the “many fish in the sea” metaphor actually works. The point, he says, is not that there are lots of fish. The point, darling, is that it’s a pain to have to share the sea with other fishermen, especially when they get lucky and you do not. But he who fishes long enough, waiting for a bite, will eventually outlast the luckier guys. He who has the sea to himself laughs last.

And If I Did, What Then?

by George Gascoigne

“And if I did, what then?

Are you aggriev’d therefore?

The sea hath fish for every man,

And what would you have more?”

Thus did my mistress once,

Amaze my mind with doubt;

And popp’d a question for the nonce

To beat my brains about.

Whereto I thus replied:

“Each fisherman can wish

That all the seas at every tide

Were his alone to fish.

“And so did I (in vain)

But since it may not be,

Let such fish there as find the gain,

And leave the loss for me.

“And with such luck and loss

I will content myself,

Till tides of turning time may toss

Such fishers on the shelf.

“And when they stick on sands,

That every man may see,

Then will I laugh and clap my hands,

As they do now at me.”

___________________________________________

With “Poem of the Day,” The New York Sun offers a daily portion of verse selected by Joseph Bottum with the help of the North Carolina poet Sally Thomas, the Sun’s associate poetry editor. Tied to the day, or the season, or just individual taste, the poems will be typically drawn from the lesser-known portion of the history of English verse. In the coming months we will be reaching out to contemporary poets for examples of current, primarily formalist work, to show that poetry can still serve as a delight to the ear, an instruction to the mind, and a tonic for the soul.