Reading Goethe With the Barbarians at the Gate

A timely reminder that art is no defense against brutality, that civilization is a thin skein easily shredded once tanks and troops start enforcing their rough rule.

‘Pollak’s Arm’

By Hans von Trotha, translation by Elisabeth Lauffer

New Vessel Press, 160 pages

While Hans von Trotha’s historical novel “Pollak’s Arm” takes place in just two rooms and features only three characters, it spans all the gorgeousness and grotesqueness of Europe’s history since the Renaissance. For those with ears to hear, this quiet, murmuring work of art yelps a howl of rage.

At a moment when war has once again come to Europe and the relationship between culture and conflict is headline news, “Pollak’s Arm” is a timely reminder that art is no defense against brutality, that civilization is a thin skein easily shredded once tanks and troops start enforcing their rough rule.

Translated from German by Elisabeth Lauffer, “Pollak’s Arm” is a love letter to art and an indictment of the barbarism that all the beauty in the world was powerless to stop. It centers on a conversation between Antica Ludwig Pollak and a German narrator tasked with ushering him to safety.

Archaeologist, art dealer, and director of the Museo Barracco di Scultura, Pollak was born in Prague and died in Auschwitz. In 1906 he discovered the long lost right arm of “Laocoön and His Sons,” one of the most extraordinary statues of the ancient world.

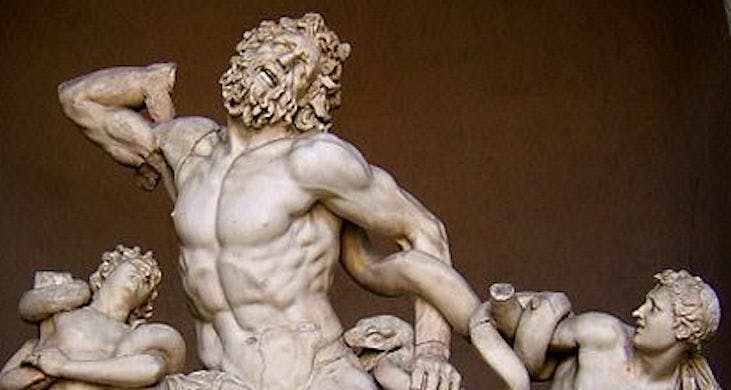

The near-lifesize Roman sculpture depicts an ancient myth told most memorably by Virgil, of a priest and his sons consumed by writhing serpents for trying to expose the Trojan Horse against the will of the gods who wanted Troy to burn.

The statue was discovered mostly intact in 1506 in Rome, with the Renaissance running at full bore. The missing pieces included the right arm that Pollak found in a builder’s yard almost exactly 400 years later. His find not only helped to complete an iconic work of art, it settled an argument — decisively showing that the arm was bent in agony, not outstretched in triumph.

“Pollak’s Arm” translates this historical material into fiction by imagining two conversations. The first is between the narrator, known only as “K.,” and an unnamed monsignor in the Vatican about an earlier conversation K. had with Pollak in the latter’s apartment, urging the art dealer to take the Roman Curia up on its offer of refuge for him and his family in the face of an imminent roundup of Jews by the SS.

While K. urges Pollak to rouse his family and flee behind the high walls of the Vatican, Pollak refuses to leave. Instead, he embarks on a string of disquisitions on Jewish and European history and the beautiful things that they made together and apart.

In a “melodic German, fetching and warm with a faint quaver that recalls old Austria and Prague,” Pollak tells K. about his life and work. Pollak was never an academic despite his vast erudition. Instead, he advised collectors. As K. explains, “the catalog is his calling. It’s his medium, his way of leaving a tangible legacy of answers, not just questions.” For Pollak, “both building a collection and cataloging it are forms of art.”

Pollak is the kind of man who says “museums are wonderful, but they pale in comparison to private collections,” who sees “truly extraordinary things hidden in plain sight among the ordinary.” He is a fixer and a counselor, a man whose internal weather is simultaneously set to Weimar and Roman skies. As both a Jew and a connoisseur, he can “never afford to make a mistake.”

Pollak is also the perfected product of the long experiment in fusing Judaism and European culture that began with the Enlightenment and ended on Kristallnacht. As he explains, “Goethe is culture, Prague is home, and Judaism is my destiny.” In his papers, tucked under sheafs of drawings and letters, is a scrap of a Torah scroll, shaped in the rough form of a Star of David.

All of this reflection is backlit with foreboding, the long shadow of Auschwitz casting a macabre light over Pollak’s musing on coins and tapestries, old Baedeakers and long ago chit chat with minor aristocracy. Pollak attended a Zionist Congress, curated ancient art, and worshipped Goethe to such an extent that he collected the poet’s letters, and emerges as an exquisite metonymy for the tragedy of Europe’s Jews.

Pollak’s belief that “we’re safe as long as we keep reading Goethe” is why the Israel Defense Forces exist. We don’t know why Pollak refused the offer of sanctuary. It could be because he saw clearly that a Rome in the process of answering the Jewish question had already betrayed everything on which Ludwig Pollak had staked his life.

Exactly 1,021 Jews boarded a train with Pollak at the Roma Tiburtina train station on Monday, October 18, 1943, at 2:05 p.m. The next day, 184 of them were selected by Josef Mengele for slave labor, with the rest sent to the gas chambers at Birkenau.

In all, a scant 16 of Pollak’s fellow passengers survived. Like the man who discovered Laocoön’s arm, it is certain that many of them loved Europe so much that it killed them.