Redeeming the Life of Jesus Christ, the Redeemer

In effect, the author is arguing that at several crucial points during Jesus’s lifetime and immediately afterward, faith in him and his message could have been destroyed if not for the efforts of his followers.

‘Miracles and Wonder: The Historical Mystery of Jesus’

By Elaine Pagels

Doubleday, 336 Pages

Jesus was not a family man. He was a bastard, and that is why the legend of the virgin birth had to be concocted. His father, Joseph, is a fiction fomented by those attempting to provide a proper upbringing for him. The resurrection? That was another fable promoted by his followers, who were shocked that he had not brought about the divinely sanctioned kingdom he had promised.

The above would be a profane reading of Elaine Pagels’s provocative new book, more delicately presented than that paragraph. In effect, she is arguing that at several crucial points during Jesus’s lifetime and immediately afterward, faith in him and his message could have been destroyed if his followers had not been forthcoming with emendations, each gospel a rewritten version of its predecessor.

A fascinating example of gospel revisionism is the treatment of Pontius Pilate, the Roman ruler who hesitated to condemn Jesus to the cross and reluctantly acceded to Jewish cries for his crucifixion. Ms. Pagels points out that the historical record does not support accounts of a Pilate with qualms, or Jews demanding his death. As with many other instances of stories that do not seem historically accurate, she seeks to explain why the obvious facts are ignored. In this case, she reminds us that early Christians feared for their lives, and so made it seem as though Roman rule had nothing to do with Jesus’s death.

The inadvertent result, however, is that the authors of the gospels incited antisemitism and the charge that the Jews killed Jesus. This was not the intention of the gospel writers, but then so much of history is about unintended consequences, as Ms. Pagels’s book shows.

Ms. Pagels identifies those parts of the gospels that elide various aspects of Jesus’s upbringing. The gospels say “nearly nothing about his family background.” He seems to have been estranged from the family. Ms. Pagels cites Mark, who reports that Jesus’s relatives were “alarmed,” that “his family went out to seize him saying, ‘He had gone out of his mind!’” (Mark 3:21). Other people in Mark’s gospel also “suspected Jesus of insanity, and that he was possessed of the devil.” Ms. Pagels notes that Jesus declares: “Prophets are honored everywhere, except in their hometown, and among their own relatives and family.”

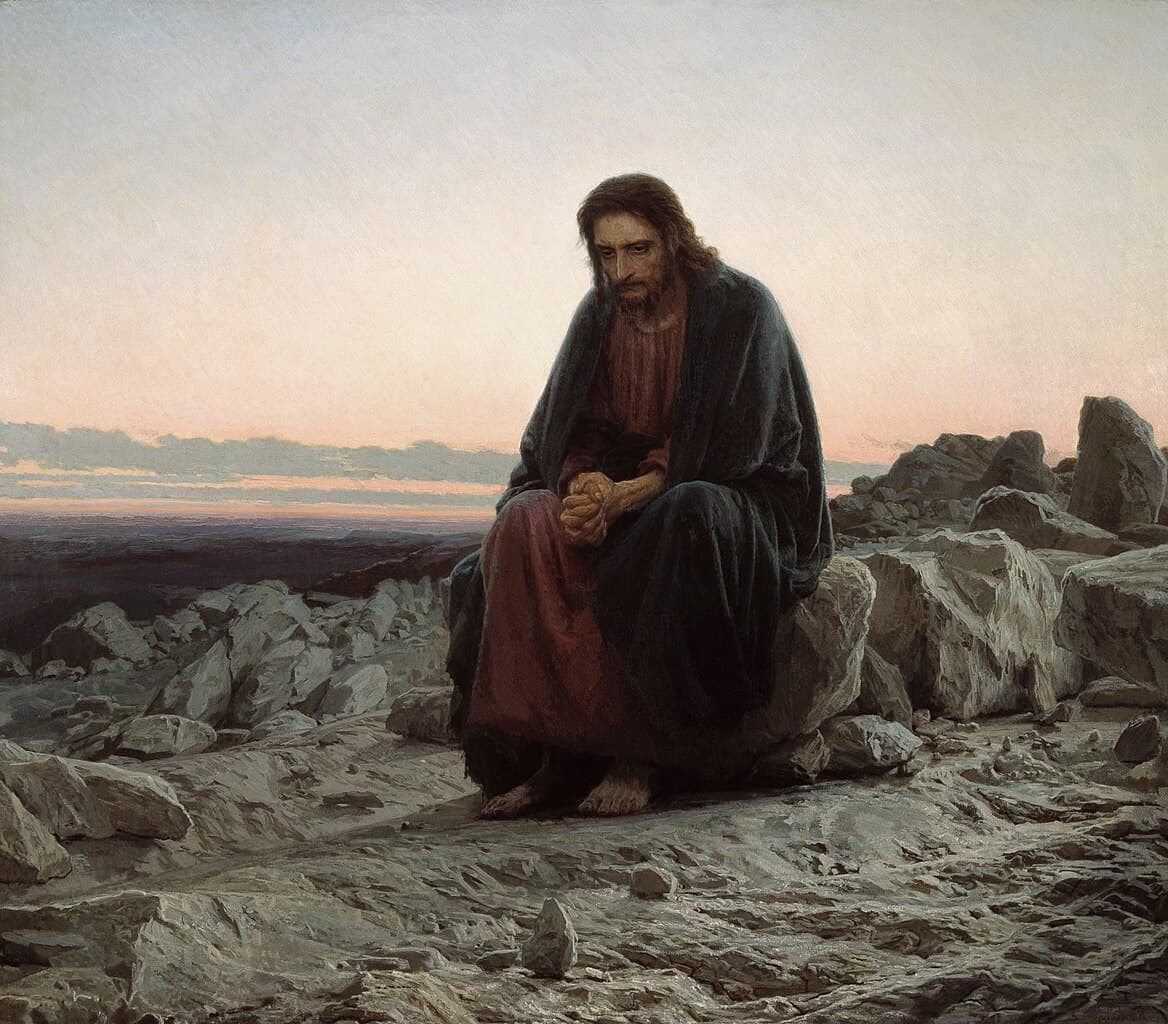

Each Christian generation, it seems, had to rewrite the story of Jesus in order to sustain their faith. But that is the point in “Miracles and Wonder.” His story about himself as redeemer transcends every discrepancy that has been detected in historical and biblical accounts.

Ms. Pagels shows that what still draws people to Christianity, especially the growing number of converts to Roman Catholicism and evangelical Christianity throughout the world, is this notion of a Jesus who looks out for you as a friend who is always there, no matter what, ready to forgive. No one is beyond redemption: This is the powerful message that peoples of all persuasions and cultures have adopted.

Toward the end of her book, Ms. Pagels explains that what she is doing is part of what is called “reception studies” — the exploration of how certain stories are told and how they are received. Ms. Pagels recognizes that she cannot settle arguments about the virgin birth or the resurrection, but she can examine how such beliefs were created and maintained.

Ms. Pagels discloses that she is a believer but not a dogmatist. She relates how as a young woman she was attracted to evangelical Christianity, then rejected it when she encountered a narrowness, bigotry, and anti-intellectual attitude among her evangelical friends.

As to matters like the resurrection, Ms. Pagels has a fascinating section on what St. Paul believed—which was not simply resurrection of the body, but something more mysterious: an afterlife to be sure, but in exactly what form is not clear in St. Paul, or in Ms. Pagels, who admits the dead have appeared as a presence in her life. She is not a mystic, but her stance clearly acknowledges the mystery that St. Paul and the early Christians experienced, and what Ms. Pagels wants to perpetuate.

Mr. Rollyson deals with reception studies in his forthcoming book, “Sappho’s Fire: Kindling the Modern World.”