Release of Black-and-White Version of Julian Schnabel’s ‘Basquiat’ Offers Opportunity To Revisit 1980s New York

While ‘Basquiat’ has something true to say, shamelessness has always been Schnabel’s primary talent and the film is no less showy, blatant, or cluttered than the smashed crockery paintings on which he established his fame.

The cinema — or, at least, fiction films — have rarely served the visual arts in a credible manner. Movies, being an inherently hyperbolic medium, tend to stretch the truth something fierce in order to make cinematic the prosaic, concentrated, and often tedious nature of putting brush to canvas, chisel to marble, or, in some cases, slopping paint on a stack of tires.

Filmmakers are drawn to overbearing or flawed artists: High drama and deep eccentricity suit the medium. All of which means that we shouldn’t hold our breath waiting for a big-budget biopic of the 19th-century American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner.

Tanner bears mentioning because of a line of dialogue in Julian Schanbel’s “Basquiat” (1996), a black-and-white version of which has been released on Blu-Ray by the Criterion Collection. Early on in the film, the poet and critic Rene Ricard (Michael Wincott) tells aspiring artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (Jeffrey Wright) that “there’s never been a Black painter in history who’s been considered really important.”

Is Ricard’s comment an indication of the character’s lack of historical knowledge or that of the film’s screenwriter, Mr. Schnabel? Truth to tell, Tanner, an African-American artist who made his reputation in France, doesn’t have much name recognition in the broader culture. Would that a U.S. museum get its act together, mount a proper retrospective, and rectify the matter. Tanner was a terrific painter.

Forgetting for a moment that there are other important Black artists who preceded “Samo©,” the graffiti tag by which Basquiat initially garnered notoriety, there is another nit to pick with Mr. Schnabel’s picture. As we watch the title character emerge from a cardboard box in Tompkins Square Park, Ricard sits nearby, scribbling in a notebook. We hear his prose in a voiceover: “The idea of the unrecognized genius slaving away in a garret is a deliciously foolish one.”

“The Van Gogh boat,” as the real Ricard noted in an essay on Basquiat, nags at a lot of creative individuals, particularly young artists who aren’t able to distinguish between artistic merit and their own self-involvement. Mr. Schnabel was into middle-age when he made “Basquiat” and knew that “no one wants to be part of a generation that ignores another Van Gogh.” Which didn’t prevent him from making a picture that shamelessly iterates a deliciously foolish idea.

Shamelessness has always been Mr. Schnabel’s primary talent and “Basquiat” is no less showy, blatant, or cluttered than the smashed crockery paintings on which he established his fame. It’s one thing to cast one’s mother, father, and daughter in small roles; it’s another to cast Gary Oldman as a version of yourself, here under the nom de plume Albert Milo. It’s to Mr. Schnabel’s credit, I suppose, that Milo is as venal as every other character in this tale of sex, drugs, and too much, too soon.

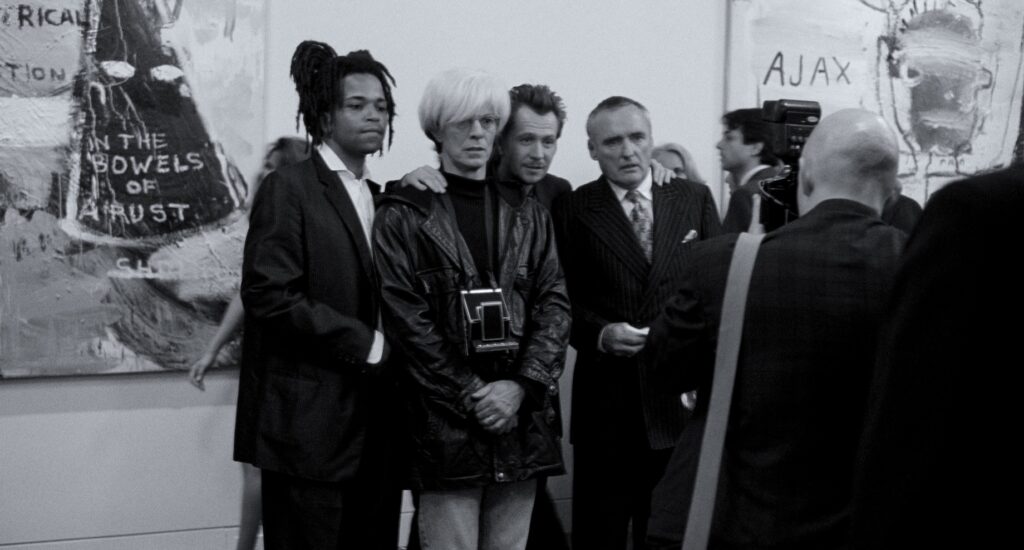

We see the actual Mr. Schnabel later on, albeit in a large portrait by Andy Warhol that serves as a backdrop for a scene in which the platinum-bewigged King of Pop collaborates with Basquiat on a series of mural-sized canvases. Their subsequent exhibition at Tony Shafrazi Gallery is the stuff of legend among downtown scenesters, not least because they’ve never been able to put a finger on just who was exploiting who: an over-the-hill doyenne of the celebrity set or a troubled striver whose star was on the wane?

“Basquiat” glances upon this dilemma, but, then, it glances on most things and to little emotional effect. When Jean-Michel cries upon learning of Warhol’s death, we have a hard time believing it because the script hasn’t done much in the way of creating characters or relationships with any depth or credence. Are most art world grandees creeps, users, sharks, and schmucks? Maybe, but cardboard silhouettes as thin as Mr. Schnabel’s do meagre service to narrative or dramatic intrigue.

Mr. Wright hits all the right buttons in the title role, Parker Posey cuts a suitably avaricious profile as art dealer Mary Boone, and B-movie cult director Paul Bartel camps it up as a one-time Metropolitan Museum of Art curator, Henry Geldzahler. Dennis Hopper is atypically restrained in his portrayal of Swiss art dealer Bruno Bischofberger and David Bowie — well, the less said the better about his performance as Warhol. Mr. Schnabel, it seems, was too starstruck by Ziggy Stardust to offer much directorial guidance.

That “Basquiat” has something true to say about 1980s New York can’t be denied, but there is a better film to be made about a super-charged and over-hyped era.