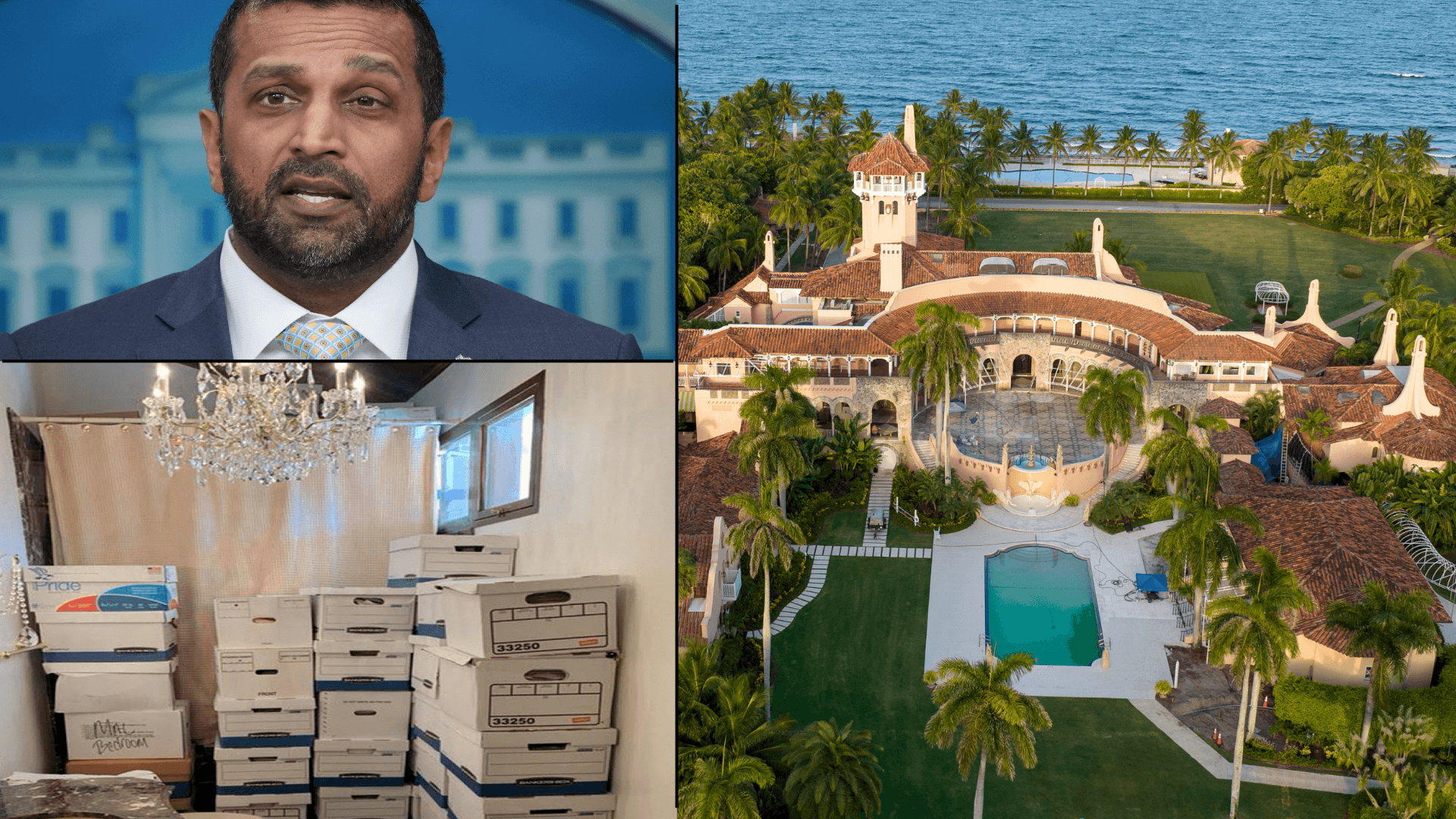

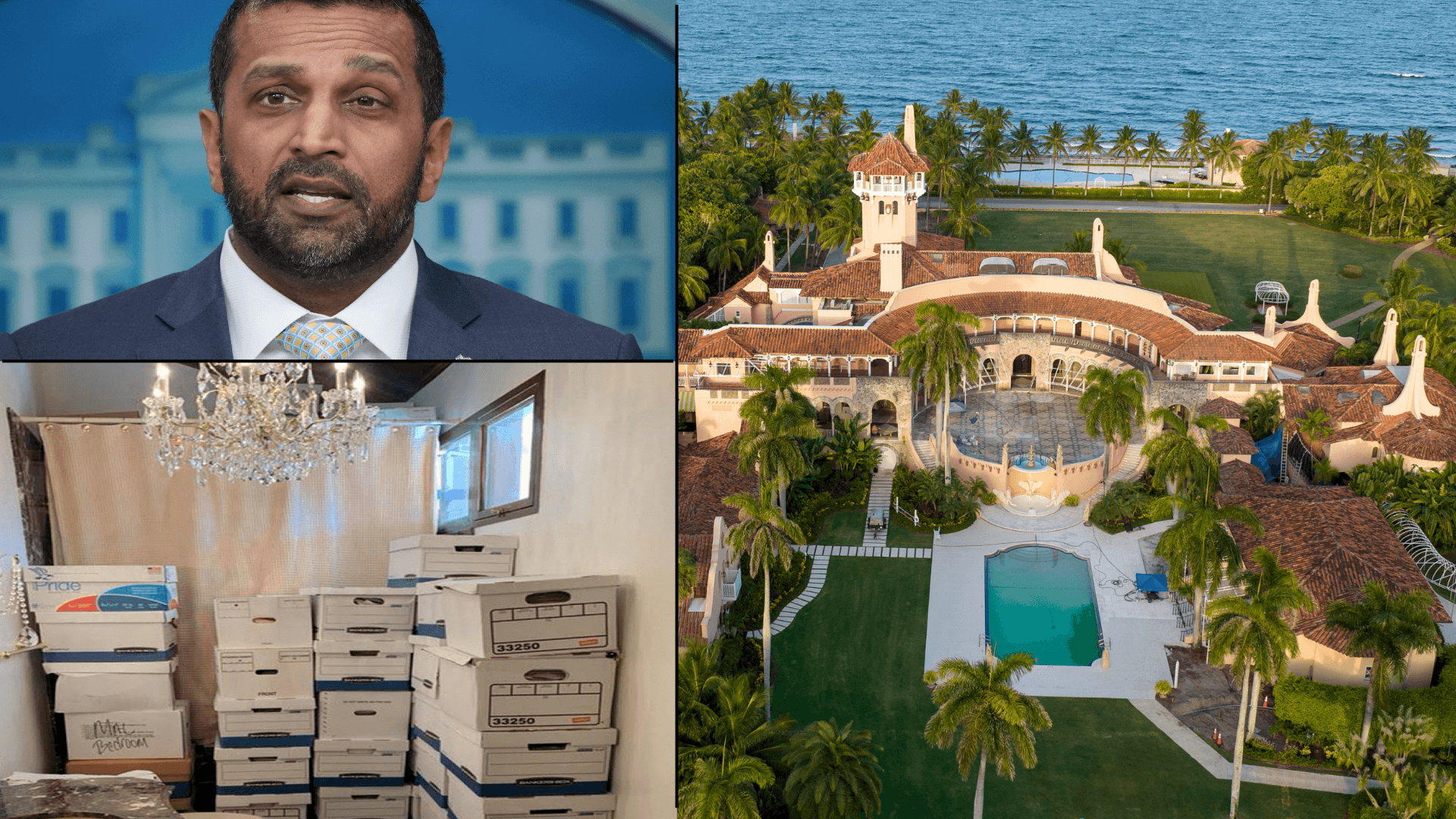

Exclusive: FBI Staffers Fired for Role in Mar-a-Lago Probe Were Assigned to Espionage Unit That Investigated Iranian Threats in America, Sources Say

By DANIEL EDWARD ROSEN

|A rash Israeli statement on Libya and the chaos at Tripoli could hurt not merely the possibility of the two countries’ relations, but also future attempts at widening the Abraham Accords.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By DANIEL EDWARD ROSEN

|

By A.R. HOFFMAN

|

By HOLLIE McKAY

|

By LUKE FUNK

|

By A.R. HOFFMAN

|

By LUKE FUNK

|

By MATTHEW RICE

|

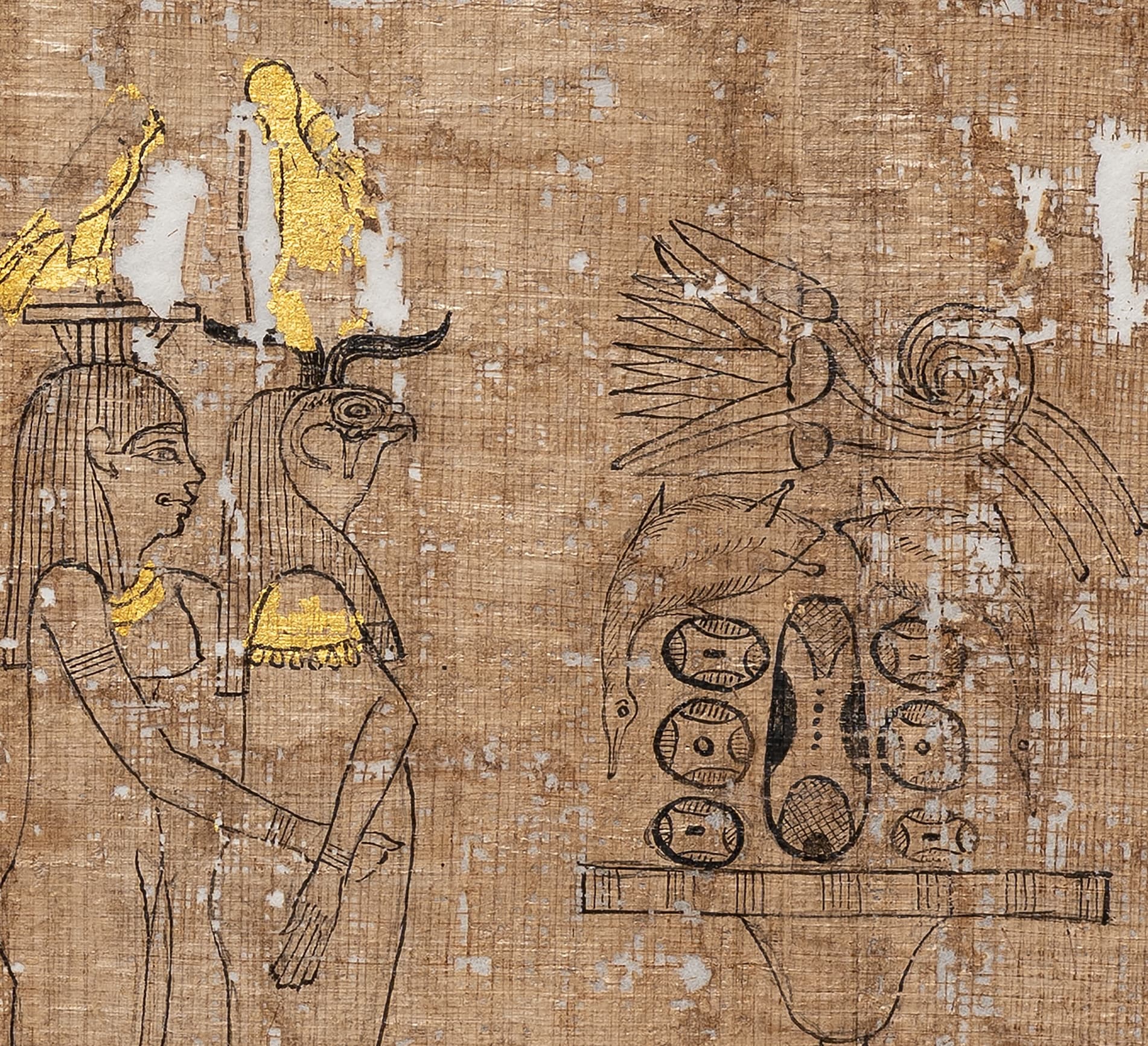

By MARIO NAVES

|