Serious About Film? You May Want To Clear Shelf Space for ‘Bresson on Bresson: Interviews, 1943-83’

‘What men have accomplished up to now in poetry, in literature, Bresson has done with cinema,’ according to Marguerite Duras. Martin Scorcese goes one better: ‘We are still coming to terms with Robert Bresson.’

The nomination of “Eo” (2022) for Best International Film at the 95th Academy Awards likely prompted an uptick in internet searches, if largely as a sidebar, for “Au Hasard Balthazar” (1966), the film from which director Jerzy Skolimowski took inspiration. Let’s hope those curiosity seekers skipped Mr. Skolimowski’s misbegotten homage and went straight to the source. Why bother with self-aggrandizing nihilism when there is grace to be had?

Mr. Skolimowski thinks the world of Robert Bresson, the French “realisateur” who helmed “Au Hasard Balthazar,” as did Andrei Tarkovsky, Jean-Luc Godard, and, of all people, Richard Hell, the punk musician who gave us that indelible paean to the perpetually disaffected, “Blank Generation.”

“Bresson,” Mr. Hell has written, “is astonishing for his utterly uncompromising fidelity to filmic values that forego all audience manipulation, all pandering for any cheap thrills.”

This statement could serve as the summa of Bresson’s aesthetic purview, the complete outlines of which are available in “Bresson on Bresson: Interviews, 1943-83,” recently published by the New York Review of Books. Let me amend that, particularly given Bresson’s insistence on the primacy of art forms: The true outlines of his vision are in the pictures, not a few of which are amongst the pinnacles of the artform. These include “Diary of a Country Priest” (1951), “A Man Escaped” (1956), “Pickpocket” (1959), “L’Argent” (1983), and “Au Hasard Balthazar.”

Edited by the director’s widow, Mylène Bresson, “Bresson on Bresson” is a chronological array of interviews whose chapters are, for the most part, predicated on each of the 12 films. That might seem a small number of pictures as far as oeuvres go, but don’t kid yourself: Their artistic worth is significant.

In the introduction, a French film critic, Pascal Mérigeau, cites a quote by novelist and playwright Marguerite Duras: “What men have accomplished up to now in poetry, in literature, Bresson has done with cinema.” Martin Scorcese, in his cover blurb, goes Duras one better: “We are still coming to terms with Robert Bresson.” Godard compared him to Dostoevsky and Mozart. Ingmar Bergman admitted that “Au Hasard Balthazar” put him to sleep, but held the rest of Bresson’s work in high esteem.

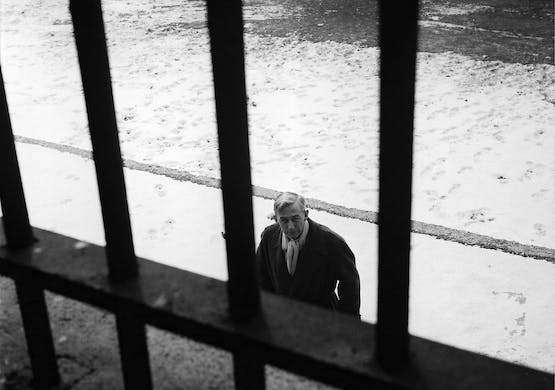

All of which Bresson himself would have likely demurred. The portrait that emerges from “Interviews 1943-83” is, if not a humble man necessarily, then one driven, ineluctably and with consummate understatement, by the prerogatives of his vision. Although trained as a painter, the only visual artist Bresson mentions with any regularity is Edgar Degas. The primary cultural touchstones are men of letters: François-René de Chateaubriand, Paul Valery, E.T.A. Hoffmann, Mallarmé, and, above all, Montaigne. “Every idle word,” Bresson the screenwriter averred, “should be counted.”

Bresson set himself apart from “the other cinema, the ones with stars and starlets.” He didn’t find much to admire in pop culture. “I want to say that we are taught—that radio, magazines, television teach us to look without seeing and to listen without hearing.” Nor was Bresson much of a movie-goer. He admired Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, liked part of “Brief Encounter” (“the half in which the characters’ faces come toward us as they plainly reveal their secrets”), and waxed enthusiastic over Mervyn Le Roy’s “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo” (1944), an MGM potboiler starring Van Johnson and an up-and-coming Robert Mitchum.

Otherwise, you know, meh. Bresson enjoyed a film by Kenzo Mizoguchi, but couldn’t remember its title. Alfred Hitchcock? Bresson knew the name but hadn’t seen any of the pictures. He was adamant that the theatrical, as he saw it, be divorced from the cinematic. Bresson cast his movies largely with nonprofessionals who bore “a moral resemblance” to his characters. Movie-making was, in the end, “a path taken in reverse, a step-by-step retreat, full of choices, puzzles, redactions, interpolations that arrive inevitably at the origins of the composition: that is, at composition itself.”

An anthology such as this one suffers from the repetition that comes from compiling a range of interviews in which similar questions asked over time reiterate similar answers. It’s unlikely, for instance, that there’s another book extant that contains the word “pleonasm” quite as much as this one. Yes, I had to look it up.

That’s a minor complaint given the opportunity to encounter an intellect who created movies like “a good craftsman loves the plank he planes.” Any serious film library should clear room on the shelf for “Bresson on Bresson: Interviews 1943-83.”