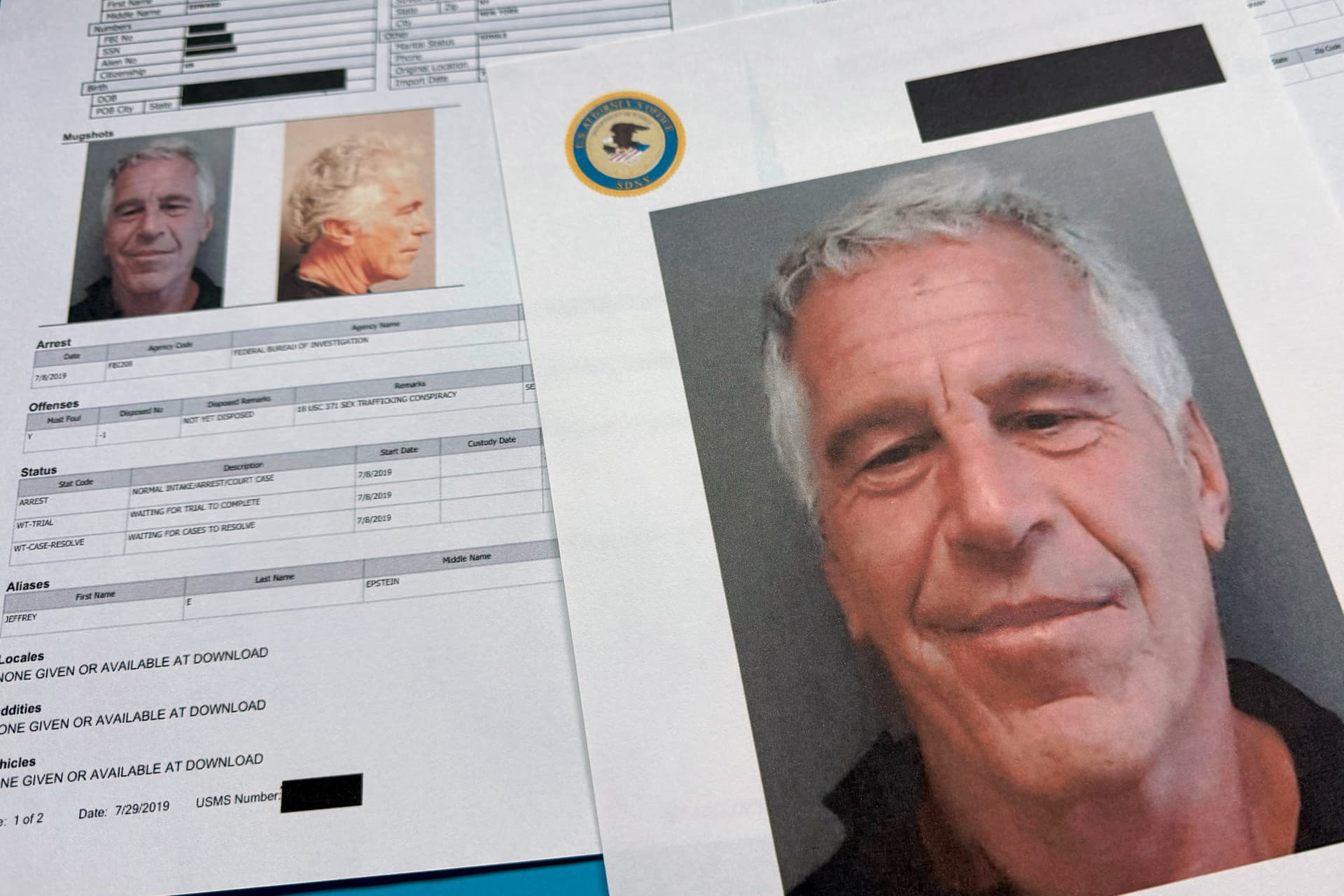

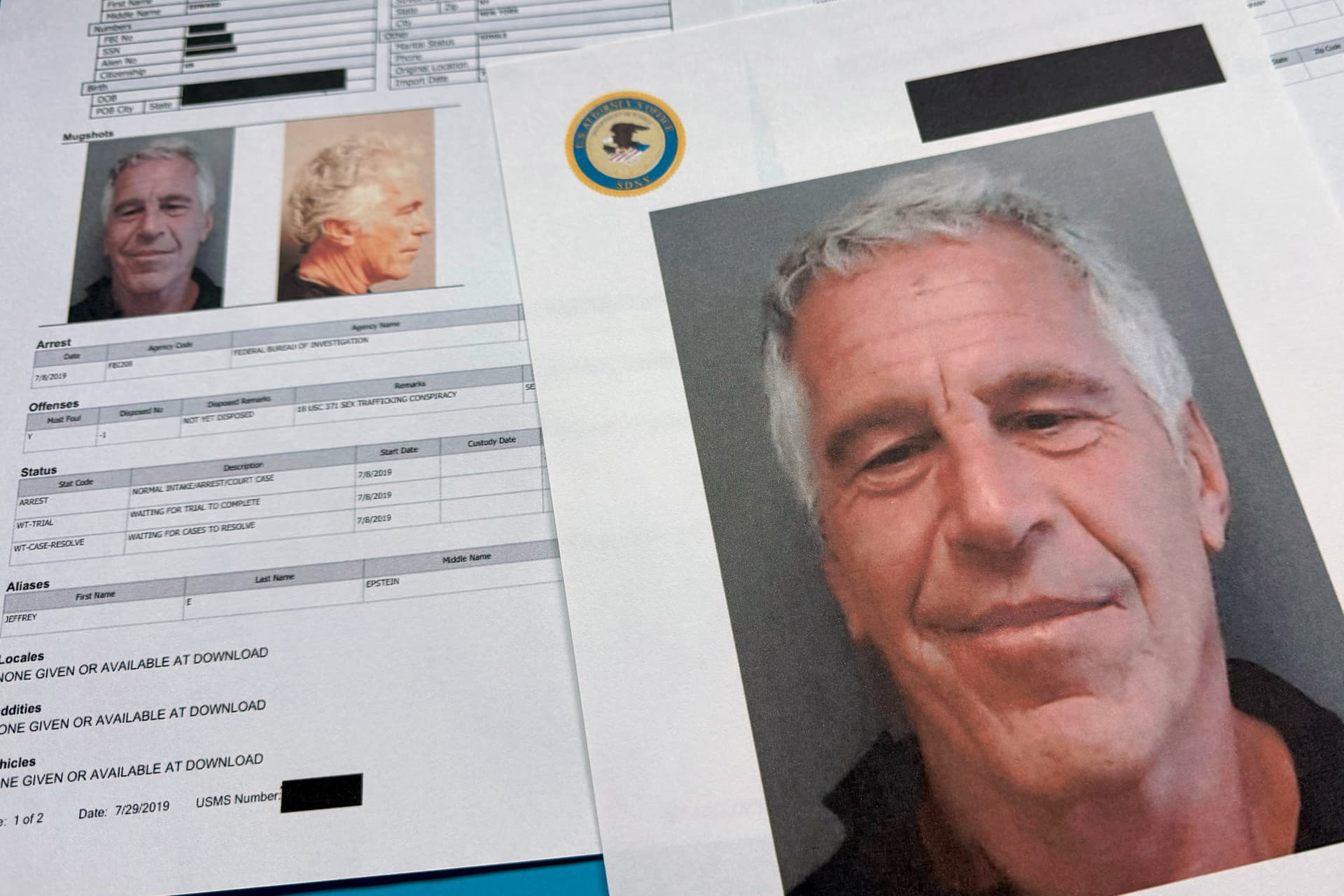

Final Release of Epstein Files Details Ties to Tech Titans and Top Officials but Fails To Satisfy Critics

By JOSEPH CURL

|After having some of the grape’s confusing distinctions explained to her, a client was grateful for the added context and jumped at the chance to explore some new avenues of wine.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By JOSEPH CURL

|

By JAMES BROOKE

|

By CAROLINE McCAUGHEY

|$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.