Pam Bondi Plows Past ‘Paperwork Mistake’ To Revive Criminal Prosecutions Against Letitia James and James Comey

By A.R. HOFFMAN

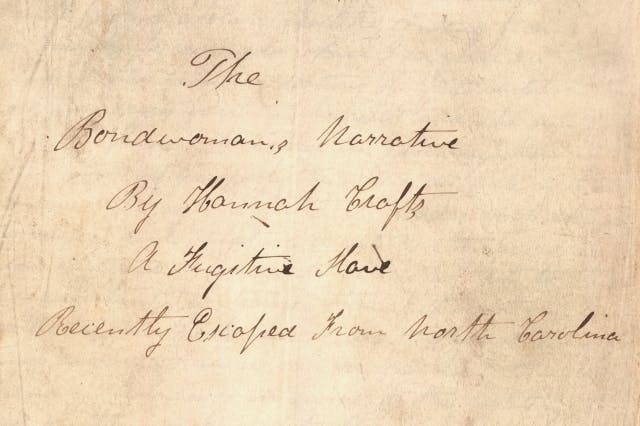

|Certain scholars doubted an ex-slave could have written ‘The Bondwoman’s Narrative,’ a novel that channeled Dickens’s ‘Bleak House’ and evinced familiarity with the genres of gothic and sentimental fiction.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By A.R. HOFFMAN

|

By ADRIAN NGUYEN

|

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT