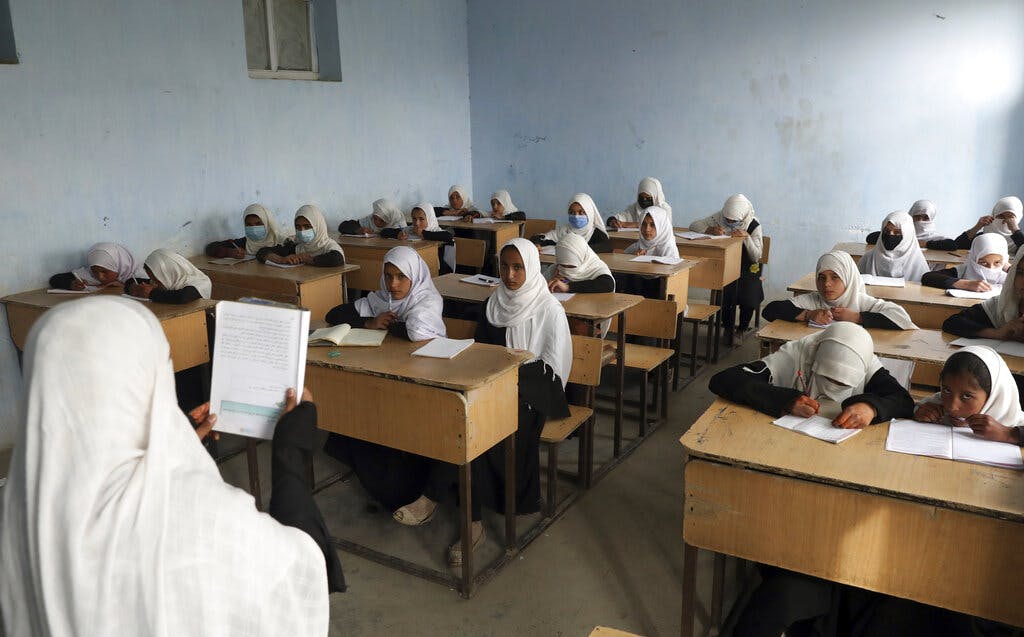

Taliban Reneges on Promise To Allow Girls To Go to School

The reversal bodes ill for America’s interests in South Asia, as it could push Afghanistan further to the arms of America’s enemies.

The news this morning that the Taliban are reneging on a promise to allow girls to go to school bodes ill for America’s interests in South Asia, as it could push Afghanistan further to the arms of America’s enemies.

Just last week the Taliban announced that schools for girls would open in Afghanistan this morning. The British Broadcasting Corporation, however, reports that when girls arrived at their place of learning, they instead saw a note that read, “We inform all girls’ high schools and those schools that [have] female students above class six that they are off until the next order.”

A posting on Twitter by the BBC shows a heartbreaking video of a young girl who, having been turned away from school, is weeping. “Mum, they didn’t let me enter my school. They’re saying girls aren’t allowed,” the posting says.

The BBC reports that this is being met with a major outcry from Afghan girls, their parents, and educators. Not that the Taliban’s abrupt backtrack is at all surprising. The Islamist group includes some members who want to coax foreign aid, and therefore would make gestures to would-be world aid donors.

Others, though, insist on following every iota of their extreme interpretations of Islam, including keeping girls in shackles of ignorance. The Taliban is the group left to rule Afghanistan after President Biden surrendered the country last year. The reversal on girls’ schools, in any event, poses a dilemma for America as to whether to help.

This is particularly true because Afghanistan is a country with no discernible economy, other than foreign donations. Aid dwindled nearly to zero after the Taliban took over, and sanctions were widely imposed. Famine, lack of bare necessities, and general poverty are rampant.

The United Nations, nongovernmental organizations, the World Bank, and the United States Agency for International Development struggle with how to deliver aid without assisting sanctioned Taliban leaders.

As a senior USAID official put it in a recent briefing with reporters, “we are saying that you cannot provide material support to certain sanctioned individuals but we don’t want to cut off the country of Afghanistan, the people of Afghanistan from the resources they need to live and to try and address the economic and humanitarian crisis there.”

That formulation troubles countries, like America, that condition aid on certain measurable human rights matrices. High on that list is equal rights for women, especially the right of education for all, including girls. Then there are countries like Russia and Communist China that care more about their spheres of influence than they do about such issues as girls’ education.

At the United Nations, in a recent vote in the Security Council to renew the mandate of the organization’s mission in Afghanistan, Russia was the only council member to abstain. Moscow’s envoy to the world body, Vasily Nebenzya, warned against pursuing “irrelevant” goals, including, presumably, girls’ education. Beijing’s ambassador, Zhang Jun, voted for renewal, but said he still has “doubts as to whether the tasks laid out in this mandate are appropriate.”

Beijing, meanwhile, is not waiting for the UN to resolve questions on how to deliver aid to a country where schooling-deniers control most of life’s aspects. Later this month, China is scheduled to lead a visiting group of foreign ministers from Afghanistan’s neighbors, including, most prominently, Pakistan, which backs the Taliban. The undeclared aim of the meeting is to bolster the Taliban’s stronghold on the country for the sake of “stability.”

Much was said about the damage from the American surrender of Afghanistan. Leaving behind a country that enslaves women mocks President Biden’s vow to put human rights at the top of his foreign policy agenda. It also allows Beijing and Russia to take over a strategic position in South Asia.