Team Trump Teases ‘Extortion Defense’ in Stormy Daniels Porn Star Case

As New York County weighs charging the former president, the lines of legal battle are coming into focus.

In 1799, President Washington wrote to John Trumbull from Mount Vernon that “offensive operations, oftentimes, is the surest, if not the only (in some cases) means of defense.” He was warning of the “evil arising from the French getting possession of Louisiana and the Floridas.” Napoleon Bonaparte was making his move.

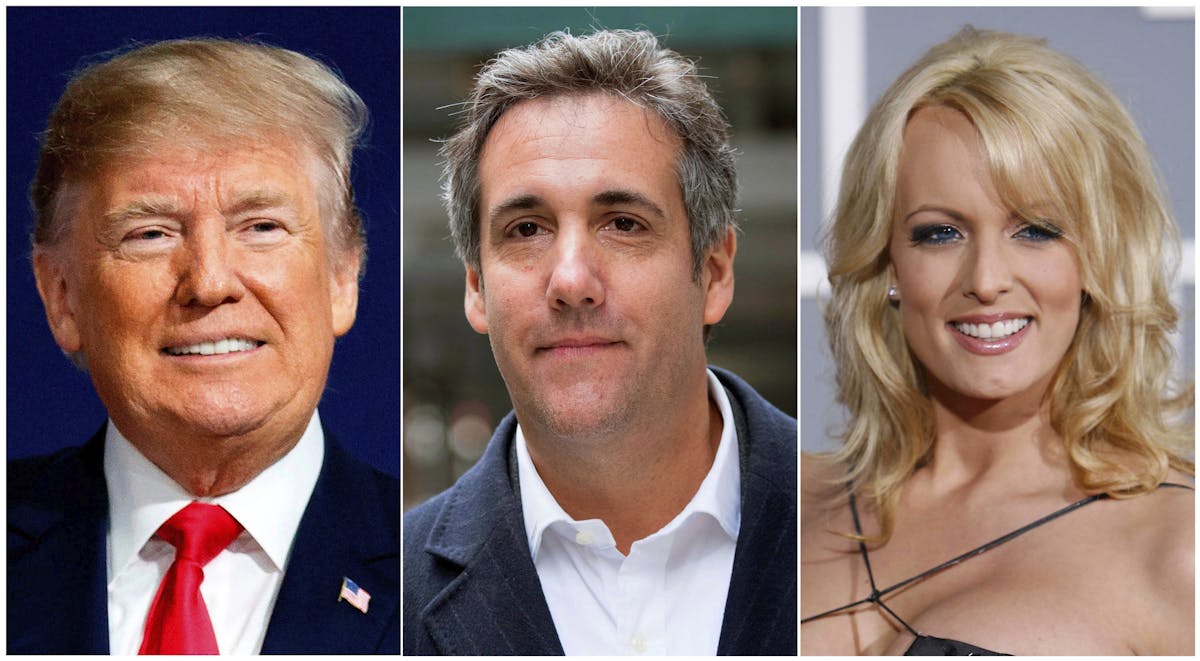

That offense can be the best defense seems to be emerging as a guiding principle of President Trump in the case being readied against him by the Manhattan district attorney. The casus belli is an alleged hush money payment seven years ago to the porn star Stormy Daniels. Mr. Trump’s counter attack — accuse Ms. Daniels of extortion.

That is what is coming into focus, after a circuitous route, as to both the nature of the case against Mr. Trump as well as the possible defense tactics. This is happening as the former president’s latest campaign for the White House picks up speed. Also accelerating are criminal probes in Georgia, Palm Beach, and Washington, D.C.

Prosecutors in New York County are telegraphing that they plan to hand up criminal charges that grow from those payments, which were handled, with commission, by Mr. Trump’s lawyer at the time, Michael Cohen. Building those charges, however, will not be straightforward.

The contours of New York’s criminal code could be one of Mr. Trump’s advantages in trying to beat the government’s rap. In the Empire State, falsification of business records — say, marking a payment to Ms. Daniels as a legal fee or deploying funds from the Trump Organization — is only a misdemeanor, punishable by a maximum fine of $1,000 and/or 364 days in jail. A judge can opt for probation.

To get to a felony, and threat of time in the big house, prosecutors would be required to stitch that misdemeanor together with evidence that Mr. Trump knowingly concealed evidence of a campaign finance violation. In concert, those behaviors would amount to a Class E felony, which in New York carries a minimum prison sentence of a year.

The Sun spoke to a law professor at New York Law School, Anna Cominsky, who cautioned that the potential reliance on campaign finance violations amounts to a “novel theory” untested in a court of law. The government will have to convince jurors that the payments were “a direct donation” to the campaign. This is not necessarily fatal; the law, she observes, “gets made by novel cases.”

The Associated Press is reporting that on Monday, Cohen testified before the grand jury contemplating charges against Mr. Trump. The disgraced lawyer pleaded guilty in 2018 to facilitating payments to Ms. Daniels and another woman, and served some time behind bars and the rest under supervised release. Of his recent testimony, Cohen has asserted that his “goal is to tell the truth.”

Prosecutors will likely point to a sentencing memorandum issued at the time of Cohen’s plea, which found that he “acted in coordination with and at the direction of” Trump, a.k.a., “Individual-1.” That plea has always been controversial, because it would suggest that Mr. Trump was part of a plot when, in fact, it arises not from a proper trial but from Cohen’s account.

Mr. Trump has always denied a plot. In either case, it would take more than that to send away the former president. The government would have to show that Mr. Trump was motivated not by personal shame, but political aspiration. Lawyers call this “scienter,” or a culpable frame of mind. Cohen’s testimony is the lynchpin. The former fixer has said that Mr. Trump “knew about everything” he was doing.

Given Cohen’s history, his credibility could appear tattered before a jury. Mr. Trump’s attorney, Joseph Tacopina, calls him a “convicted perjurer” and a “liar” with “zero credibility” and speculates that he does not think Cohen even ”had a law license, quite frankly.” Expect that argument to be made at length during cross-examination if there is a trial.

The acquittal of a former presidential candidate, John Edwards, stands as a cautionary tale. The Tar Heel State senator was prosecuted for violating federal campaign laws stemming from payments made to his mistress and mother of his daughter. A jury acquitted him on one count and hung on the others, persuaded that the motivation for the payments was not political, but rather to hide the affair from his cancer-stricken wife.

Mr. Tacopina appears to be preparing another defense. He went on Sean Hannity’s Fox News television program on Monday evening and called his client an “extortion victim,” because Ms. Daniels “came out right before the election and said, unless you pay me, I am going to make a public story about something” — that “something” being the allegation of a tryst that Mr. Trump says is “completely untrue.”

A statement from Mr. Trump’s campaign, issued last week, made the same point, claiming that “President Trump was the victim of extortion” and that his potential prosecution is an “embarrassment to the Democrat prosecutors, and it’s an embarrassment to New York City.”

Ms. Cominsky labels an extortion defense as “tricky” because Mr. Trump would have to admit that he knew the payment was going to Ms. Daniels. She would advise him to “distance himself from the payment,” and not admit to being forced into making it. She warns Mr. Trump’s team that the district attorney, Alvin Bragg, is “a smart prosecutor.” She does not “doubt his decision making.”

The New York penal code ordains that a “person obtains property by extortion when he compels or induces another person to deliver such property to himself or to a third person by means of instilling in him a fear that, if the property is not so delivered, the actor or another will expose a secret or publicize an asserted fact, whether true or false, tending to subject some person to hatred, contempt or ridicule.”

In 2018, the publisher of the National Enquirer, American Media Inc., admitted, in the words of the United States Attorney’s Office, that it “made the $150,000 payment in concert with a candidate’s presidential campaign, and in order to ensure that the woman did not publicize damaging allegations about the candidate.”

In the tabloid business, this is known as “catch and kill.” In other words, Ms. Daniels approached the editors of the National Enquirer with her story, and the tabloid mavens, in sync with Cohen, offered to pay for the story only to keep it under wraps. This was the set of facts to which Cohen confessed.

The specter of extortion has long stalked the furore between Ms. Daniels and Mr. Trump. The lawyer she hired to represent her against the former president, Michael Avenatti, was himself convicted for attempting to extort Nike to the tune of $25 million. He has also been convicted of wire fraud and identity theft in connection with his representation of Ms. Daniels.

A more effective, albeit less evocative, defense for Mr. Trump than extortion could be citing the statute of limitations. In New York, misdemeanors must be prosecuted within two years, and Class E felonies — the lowest level — have to be prosecuted within five years. His lawyers will likely contend the clock has hit 00:00.

Befitting a man who next year could both stand trial and stand for president, Mr. Trump, in an effort to solder a bond with voters, writes on Truth Social that “Remember, any indictment of ME is an indictment of YOU. If they can indict ME for paying $130,000 in hush money to a porn star, they can indict YOU for paying $130,000 hush money to a porn star.”