Tenure of Special Master in Mar-a-Lago Case Is Over, and Trump’s Troubles Could Be Just Beginning

An appellate panel strikes down a major obstacle to indictment.

The decision by a panel of three riders of the 11th United States appeals circuit to nix the special master appointed by Judge Aileen Cannon is a repudiation of President Trump’s theory of the case that could put him behind bars.

The possibility of criminal charges for Mr. Trump harboring documents at Mar-a-Lago comes into focus as the panel ruled that Judge Cannon overstepped her authority in appointing another judge, Raymond Dearie, to superintend the case.

In a 21-page, unsigned opinion, the panel of riders — all nominated to the bench by Republican presidents — articulated fear of a precipitous slippery slope. They fretted that allowing the special master in this case would open the door to such an appointment for every aggrieved subject of a search warrant.

Even as the riders worried about a criminal system grown lousy with special masters, they refused to make a distinction for the former president. Mr. Trump’s lawyers had insisted that his status as a one-time chief executive warranted a special master to chaperone the government’s use of evidence.

The appellate panel displayed special sensitivity to separation of powers. The members reasoned that allowing the special master to continue his work — a final report was due December 16 — would “violate” that constitutional “bedrock.” Once a warrant is secured, the Department of Justice generally has free rein to build its case.

The special master’s remit was to evaluate the documents seized to detect executive or attorney-client privilege. If Mr. Trump wants to make those claims, he will now have to do so after a potential criminal indictment, in anticipation of, or during, trial.

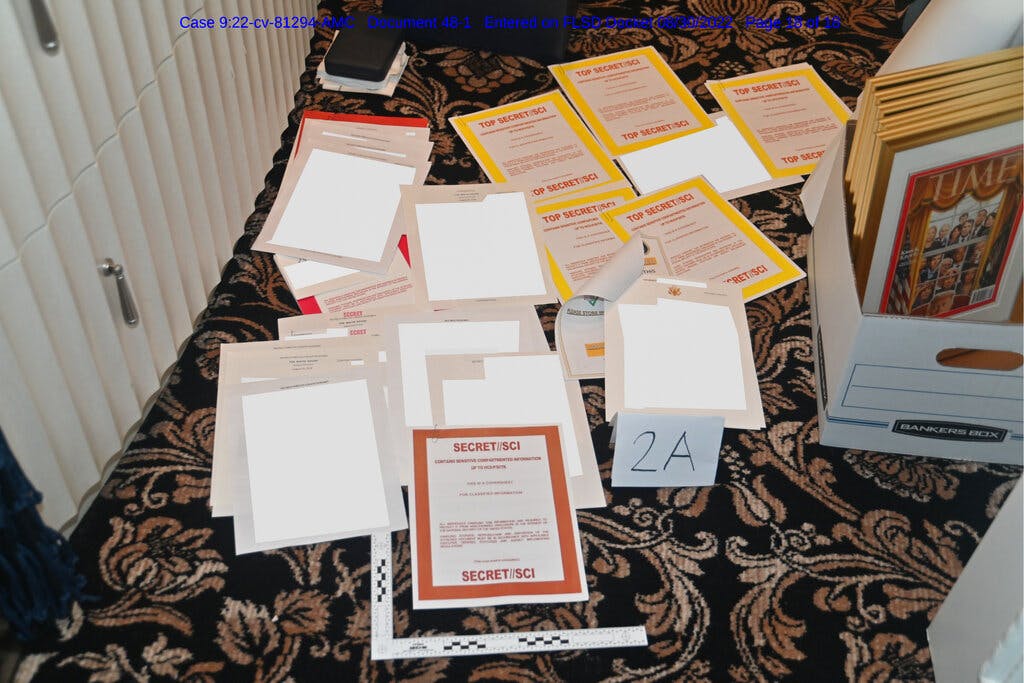

In declining to “carve out an unprecedented exception in our law for former presidents,” the 11th Circuit frees up the DOJ to scour the 13,000 documents and more than 22,000 pages that it recovered from Mar-a-Lago for evidence of criminality on the part of Mr. Trump.

The riders detected in Mr. Trump’s argument a “recurring theme” that troubled them; his arguments would “allow any subject of a search warrant” to move for a special master. Such recourse, they insist, must exist only when a “callous disregard of constitutional rights” has already marred the government’s actions.

The decision states that this “callous disregard standard has not been met here, and no one argues otherwise,” meaning that Mr. Trump’s team has not shown that the government’s behavior was out of the ordinary, let alone egregious enough to call for such an unusual remedy as a special master.

In the absence of such a demonstration by Mr. Trump’s attorneys, the panel lands on the kind of “restraint” that “guards against needless judicial intrusion into the course of criminal investigations — a sphere of power committed to the executive branch.” In other words, the brief era of the special master in this case is over.

Quickly disposing of Mr. Trump’s argument that the records found at Mar-a-Lago are his personal property, the judges note that “any subject of a search warrant would like all of his property back before the government has a chance to use it,” meaning that Mr. Trump, as opposed to being a unique litigant by dint of his former office, is a judicial everyman.

Mr. Trump’s arguments amount to what the riders call a “sideshow.” They elaborate that it is “indeed extraordinary for a warrant to be executed at the home of a former president — but not in a way that affects our legal analysis.”

Pending appeal, that analysis spells the end of Judge Dearie’s work. In refusing to grant a “special exception” to Mr. Trump, the 11th circuit has cleared the way for the government to indict. All eyes are now on the DOJ.