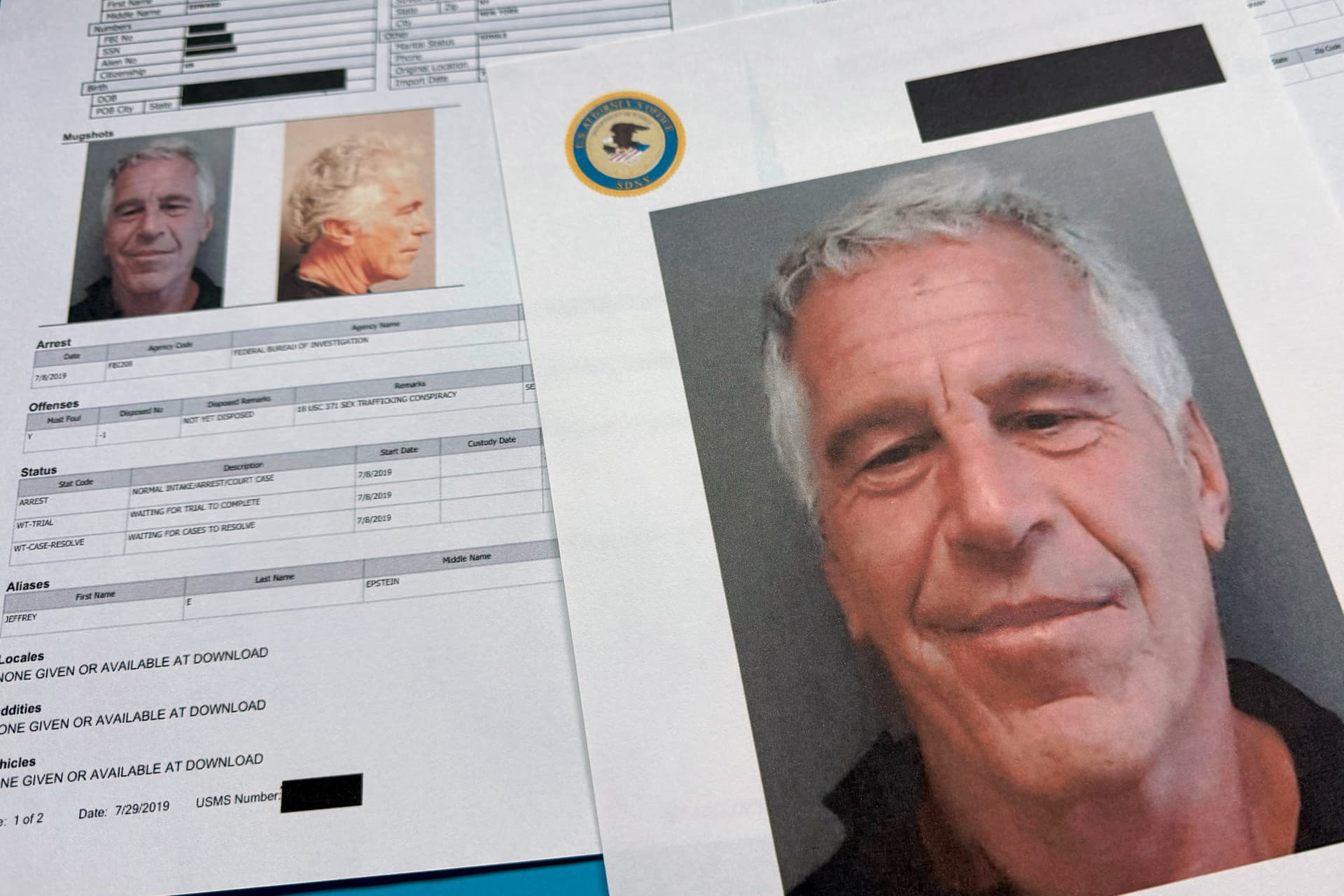

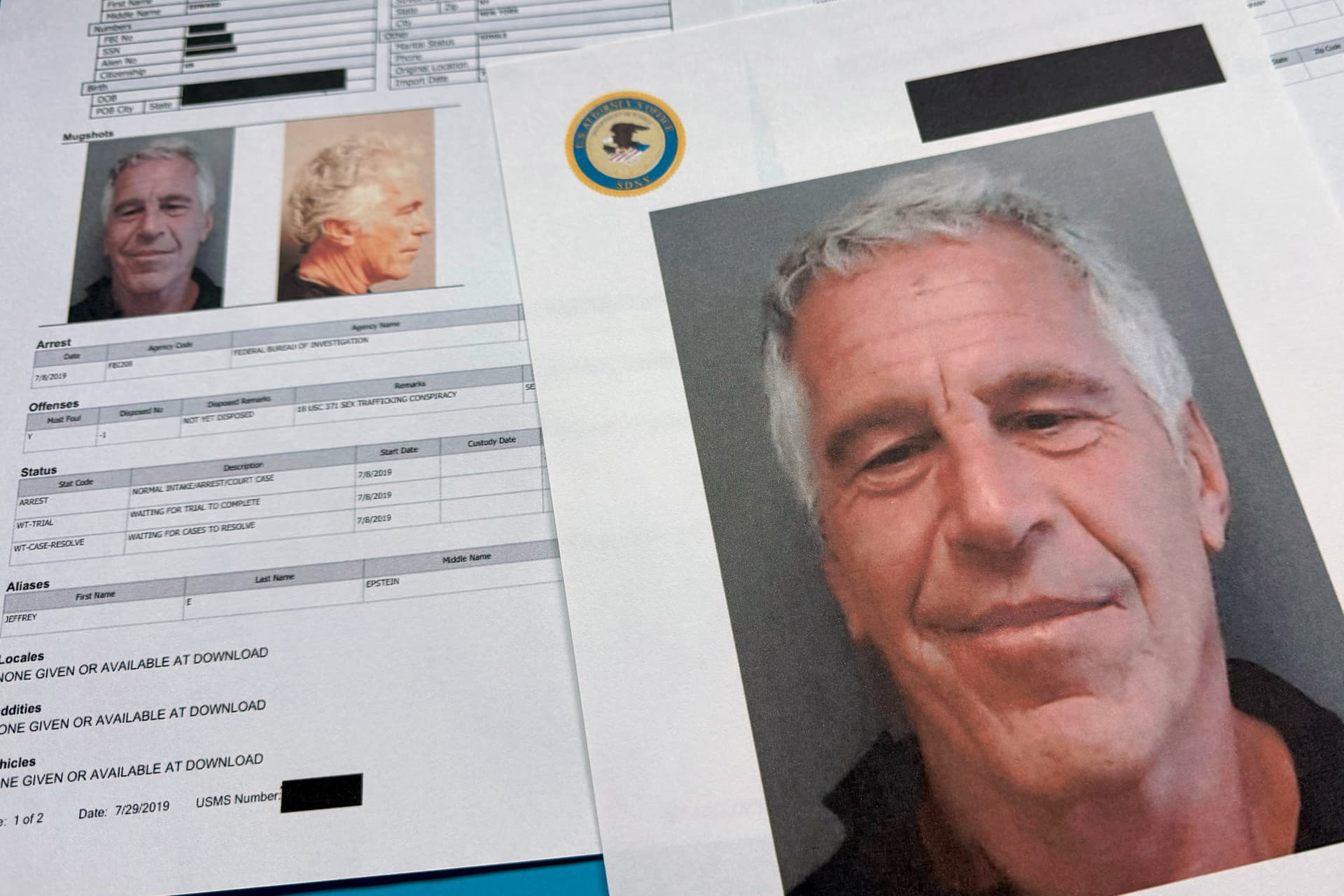

Final Release of Epstein Files Details Ties to Tech Titans and Top Officials but Fails To Satisfy Critics

By JOSEPH CURL

|Accomplished biographer Paul Alexander concentrates on an artist capable of sublime performances even in physical and mental extremity. It is not too much to say that Holiday lived to sing.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By JOSEPH CURL

|

By JAMES BROOKE

|

By CAROLINE McCAUGHEY

|

By LUKE FUNK

|

By A.R. HOFFMAN

|

By NOVI ZHUKOVSKY

|

By SALENA ZITO

|

By MICHAEL BARONE

|