The Death, Amid a National Crime Wave, of the Father of Three-Strikes Laws Underscores Pendulum Swing to Criminals From Victims

Those suffering violence from career criminals cry out for security, as Michael Reynolds did after his daughter was murdered, and seek the justice they feel prosecutors and judges don’t deliver.

America is weighing the legacy of a California photographer, Michael Reynolds, upon his death at 79, recalling his crusade for the nation’s first three-strikes law amid a crime wave in the 1990s and asking if his blueprint is a solution for safer streets today or too blunt a tool for the job.

In 1992, two men on motorcycles ambushed Reynolds’ daughter, Kimber, an 18-year-old college student, demanding her purse. When she refused, Reynolds told NPR in 2009, “one of the men, without warning, literally without provocation, pulled out a .357 Magnum — which is one of the most powerful handguns in the world — and placed it in her ear and pulled the trigger. Executed her on the spot.”

As Reynolds sat at Kimber’s deathbed during the 26 hours it took for her life to ebb away, he sought to spare others her fate. “I promised her,” he said, “that if I could do anything to prevent this from happening to other kids, I would do everything I could.”

These feelings hardened when Reynolds learned that Joseph Davis, who pulled the trigger, and his accomplice, Douglas Walker, were repeat offenders. “It became apparent,” Reynolds said, “that the system itself was re-releasing the same offenders over and over again.”

Davis later died in a shootout with police, but Walker was arrested and agreed to a plea deal: A nine-year sentence with the possibility of parole after serving half that. Seeing this as insufficient, Reynolds made it his mission to limit repeat offenses, choosing the arbitrary number of three strikes from baseball.

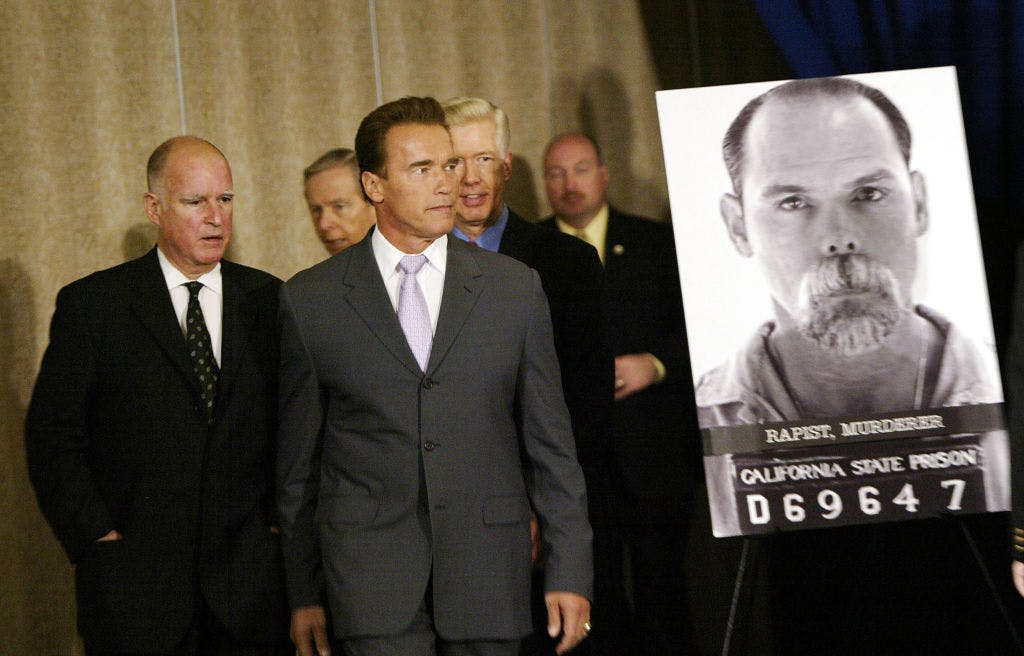

Thanks to Reynolds’ lobbying, California’s legislature passed and its Republican governor, Peter Wilson, signed, the first three-strikes law which doubled the penalty for a second conviction and carried a mandatory prison sentence of 25 years to life for a third.

In the years that followed, 28 other states adopted three-strikes laws, but only California allowed a non-violent or low-level felony to count as strikes two and three if strike one was for a violent or serious offense. This drew criticism from those who felt the penalties were too harsh and would overcrowd prisons.

“In 1994,” according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office, “analysts predicted that Three Strikes would result in over 100,000 additional inmates in state prison by 2003. Clearly, that rate of growth has not occurred,” but “strikers” accounted for about a quarter of California’s prisoners.

California’s violent crime rate, already on a downward trajectory, declined by 43 percent in the decade after the law went into effect, but this reflected a national trajectory. Just how much was because criminals avoided a third strike and how much is due to other factors is hard to quantify.

Three strikes did deliver a measure of justice for Kimber Reynolds. In April 2009, Walker was convicted of domestic violence and sentenced to life. “In announcing the punishment,” the Fresno Bee reported that Judge W. Kent Hamlin “noted that Walker has three prior strikes for robbery and attempted robbery and four prior prison commitments.”

However, when another repeat offender, Jerry Williams, was convicted of his fifth felony in 1995, he energized the opposition, since his crime was stealing a single slice of pepperoni pizza from a group dining at an ice cream shop, a petty theft misdemeanor increased to a felony due to his rap sheet.

In 2012, Californians passed Proposition 36, limiting strikes to violent offenses and giving judges the flexibility to eliminate previous offenses from the total. This brought the state in line with others, giving the justice system the flexibility to apply mercy rather than tying its hands.

Those suffering violence from career criminals cry out for security, and in places like California with the power to pass ballot initiatives, they may seek the justice they feel district attorneys and judges don’t deliver, choosing one-size-fits-all solutions to prioritize victims over those who prey upon them.

In recent years, with crime surging again, it seems the pendulum has swung too far in the other direction — toward leniency for violent criminals — as seen in measures like New York’s experiment in “bail reform,” which has turned the justice system into a revolving door for offenders.

For many of today’s lawbreakers, it’s a far cry from three strikes, as the New York Post reported last summer, with one career criminal, Harold Gooding, having been arrested 88 times since the bail changes went into effect.

Gooding is one of “a small group of just 10 career criminals,” the Post added, who have been “allowed to run amok across the Big Apple and rack up nearly 500 arrests after New York enacted its controversial bail reform law.” This soft-on-crime approach has fomented a sense of rising disorder across the city.

“Time and time again,” Mayor Adams has observed, “our police officers make an arrest, and then the person who is arrested for assault, felonious assaults, robberies and gun possessions, they’re finding themselves back on the street within days — if not hours — after the arrest.”

Illinois, too, is turning against bail in keeping with the tenets of the “anti-incarceration” movement, under the misleadingly-named Safety, Accountability, Fairness and Equity-Today Act of 2022. “Crimes including aggravated battery, arson, burglary, drug-induced homicide or kidnapping,” I wrote of the SAFE-T Act in the Sun last year, as well as second-degree murder, or even “threatening a public official such as a judge,” will no longer automatically require pre-trial detention.

The debate over how to achieve a fair balance — so victims aren’t reduced to statistics or criminals to inmate numbers — survives Reynolds’ death and keeps us talking about how best to achieve the Constitution’s goal to “insure domestic tranquility.” It’s this conversation, not three-strikes laws themselves, that could prove to be Reynolds’ most enduring legacy.