Kim Jong Un Glorifies North Korean Lives Lost in Ukraine War at Opening of Luxury Apartment Complexes at Pyongyang

By DONALD KIRK

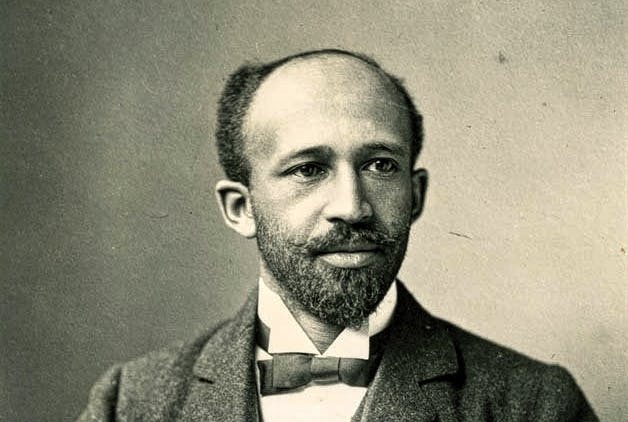

|Faulkner recognized what W.E.B. Du Bois and Frantz Fanon wrote about as an everyday reality for themselves and people of color as they protested the color line that equated being Black with inferiority.

By DONALD KIRK

|

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|

By GEORGE WILLIS

|

By MATTHEW RICE

|

By JOSEPH CURL

|

By MARIO NAVES

|

By BERNARD-HENRI LÉVY

|

By HOLLIE McKAY

|Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.