The Einstein of Early Christendom

Bede believed in a discoverable world, as did Einstein. Divine revelation did not mean, in Bede’s case, simply receiving wisdom but, instead, required human beings to search the visible signs of God’s creation.

‘Bede and the Theory of Everything’

By Michelle P. Brown

Reaktion Books, 312 pages

Michelle Brown places Bede (circa 673-735), often given the honorific of “venerable,” in the company of Albert Einstein, who declared: “I want to know how God created this world. I want to know His thoughts, the rest are just details.”

Like Einstein, Bede believed in a discoverable world. Divine revelation did not mean, in Bede’s case, simply receiving wisdom but, instead, required human beings to search the visible signs of God’s creation — even as he spent decades studying the work of the patristic fathers and explaining, like a modern scholar might, the language of the Bible, deciphering what was literal and what was symbolic or allegorical.

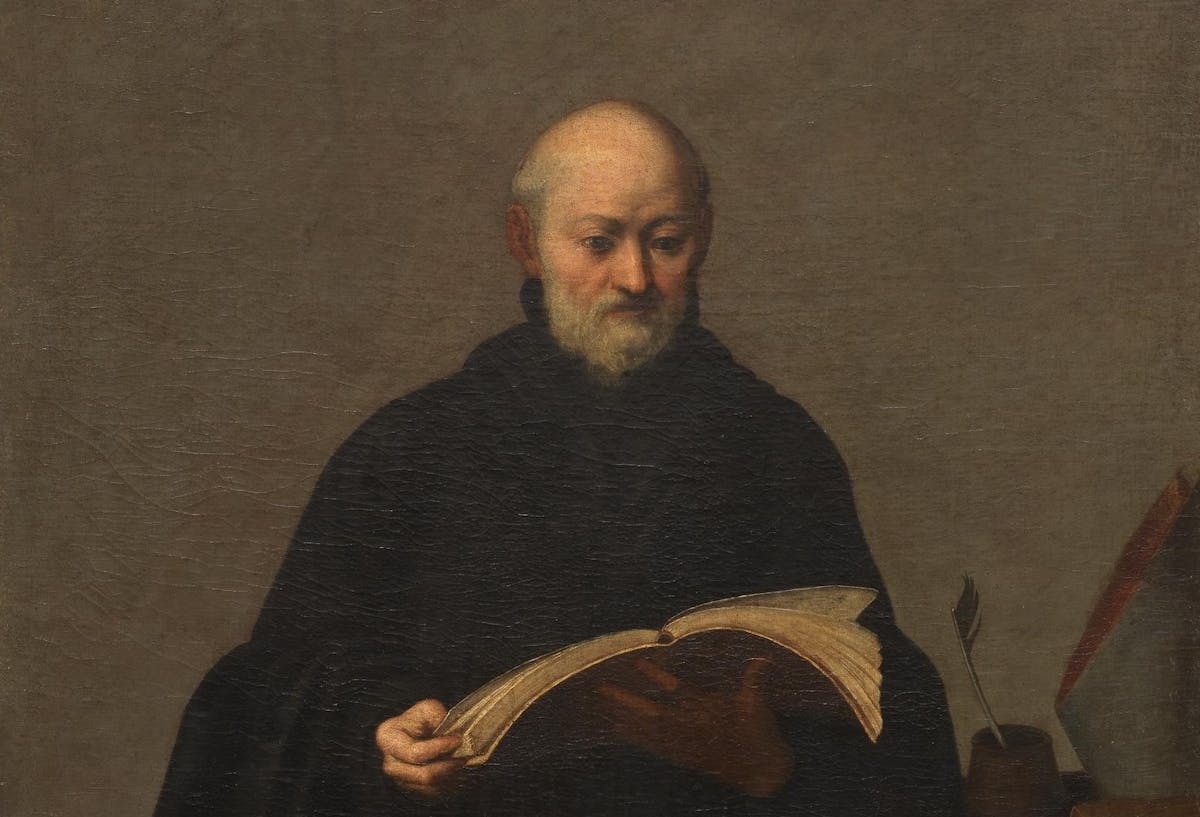

Bede is most famous for his “Ecclesiastical History of the English People,” a work that solidified the English church in the realm of Christendom and made it the site of much contestation about the nature of the true religion. A priest and monastic, Bede impressively engaged with both the institutions of the church and the laity.

Ms. Brown depicts a proto-scientist who by his own reckoning could explain to the flat-earthers why the world was a sphere even as he was the first to calculate tide tables and invent footnotes — his tributes to a world of learning, which he saw as synonymous with his religious faith.

Bede was devoted to the life and teachings of St. Cuthbert (circa 634-687), a Northumbrian like Bede whose example inspired a cult opposed by another Northumbrian, Bishop Wilfred (circa 633-709), in a struggle between Roman and Celtic christianity. In other words, to revere Cuthbert meant taking a stand, acknowledging the worldly values of quarrelsome Wilfred but insisting on an austere, hermetical life as the true sign of devotion to God.

Think of Bede’s biography of St. Cuthbert as addressed not only to his followers but to skeptics, and you have a biographer not so different from one of today dealing with a controversial figure, about whom no consensus has yet formed. In a prose biography of St. Cuthbert (Bede also wrote one in verse), he speaks of his “minute investigation to write … the deeds of so great a man” with the “most accurate examination” of credible witnesses. Bede mentions that he has submitted his work to reverend brothers who have knowledge of Bede and have offered corrections.

St. Cuthbert was said to have performed miracles, and Bede is careful to describe the exact circumstances and eyewitnesses to the saint’s supposedly supernatural acts. For Bede, drawing on oral history and on the scriptures as precedents meant “everything” he had written was “by common consent pronounced worthy to be read without any hesitation.”

Yet Ms. Brown’s Einsteinian Bede sometimes takes as a standard of proof what no modern scientist can accept. To silence critics of his biography of St. Cuthbert, Bede hammers his point at the end of Chapter II: “If any one think it incredible that an angel should appear on horseback, let him read the history of the Maccabees, in which angels are said to have come on horseback to the assistance of Judah Maccabaeus, and to defend God’s own temple.”

Like other medieval Christian scholars, Bede believed in typology, the prefiguration of individuals and events in the Old Testament that led to the advent of the New. In short, Bede believed not only in his own powers of perception but in the scriptural authority of the church fathers. His dependence on authority no longer holds the same sway in our world, where we speak not of authorities but of sources of knowledge — without the reverence that made Bede’s beliefs so powerful but also precarious in a secular world.

As Ms.. Brown ably demonstrates, for Bede there was no discrepancy between his ability to study nature and to study God. They were all part of his theory of everything. She contends that scientists like Stephen Hawking, whom Ms. Brown quotes, remain in Bede’s wheelhouse, declaring: “I’m now glad that our search for understanding will never come to an end and that we will always have the challenge of new discovery. … Without it we would stagnate.”

The “parameters” of Bede’s knowledge “were more limited than ours,” Ms. Brown observes, but like Hawking, she argues convincingly, Bede sought to “expand them.”

Mr. Rollyson includes Bede’s prose life of St. Cuthbert in his anthology, “Biography Before Boswell.”