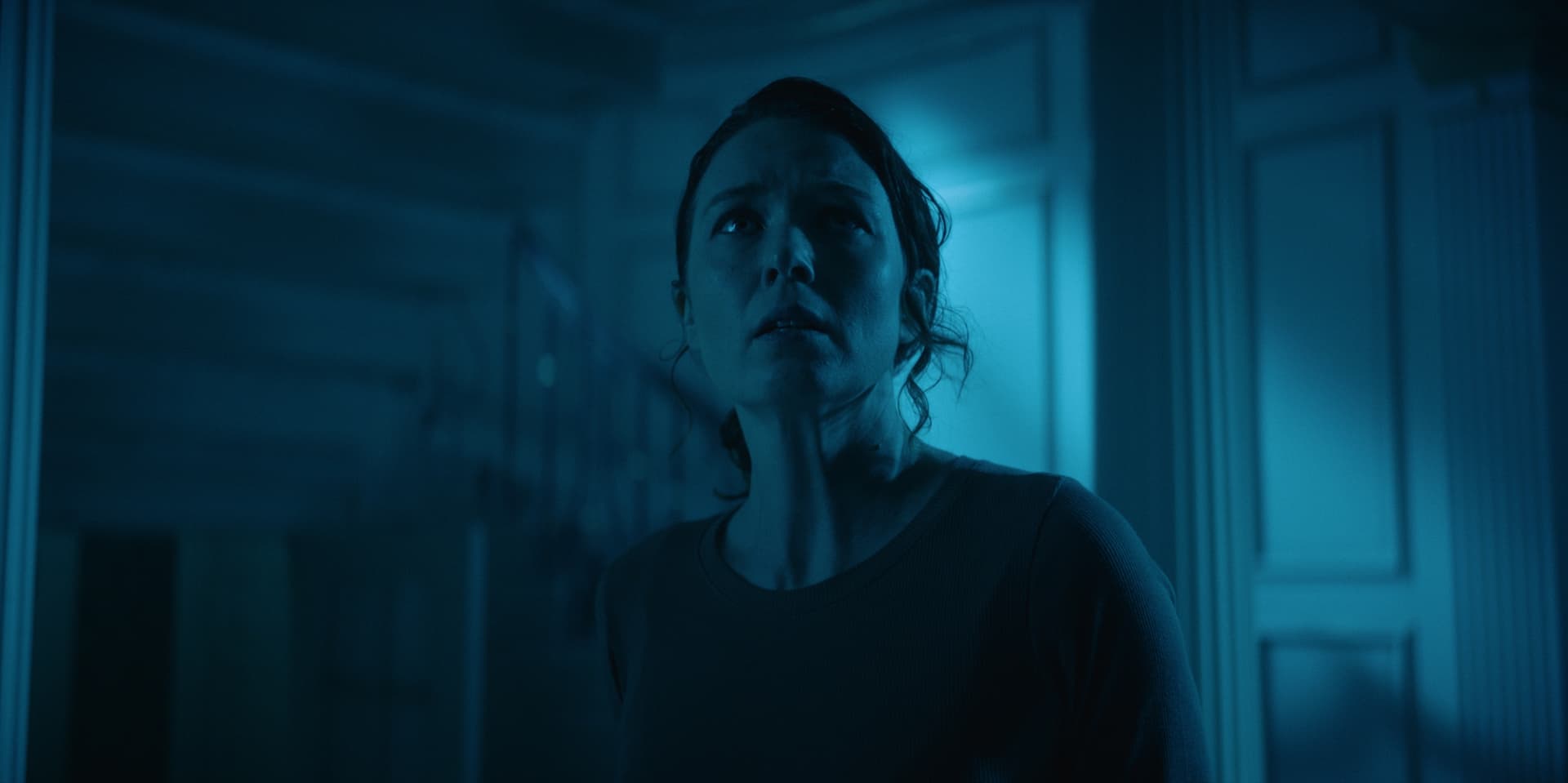

Economical Horror Indie ‘The Arborist’ Outshines Ryan Coogler’s ‘Sinners,’ in Many Respects

By MARIO NAVES

|The paranoid person is assured that he is at least worth persecuting: it lends him an importance of a kind that he would not otherwise have.

By MARIO NAVES

|

By LUKE FUNK

|

By MARIE POHL

|

By DAVID JONES

|

By NOVI ZHUKOVSKY

|

By DONALD KIRK

|

By LUKE FUNK

|

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.