The Rimbaud of Rock

‘Roadhouse Blues’ is true to its subtitle: This is biography as cultural history. Jim Morrison’s outrageous behavior only makes sense in the context of his time.

‘Roadhouse Blues: Morrison, The Doors, and the Death Days of the Sixties’

By Bob Batchelor

Hamilcar Publications, 256 pages

Jim Morrison (1943-71) cast himself in the tradition of a French poet, Arthur Rimbaud (1854-91), who in 1871 wrote as a 16-year-old: “I’m now making myself as scummy as I can. Why? I want to be a poet, and I’m working at turning myself into a seer.”

Four years later, Rimbaud was done, having managed to create a worldwide impact as poet and persona while standing aside from society, dooming himself to a solitary but glorious place on Parnassus.

Morrison died at Paris at 27 in occluded circumstances that preserve the mystery of a figure firmly on William Blake’s road to excess. In Bob Batchelor’s account, the drinking and drugged-out Morrison nonetheless provided a sobering diagnosis of his society’s complacency and conformity.

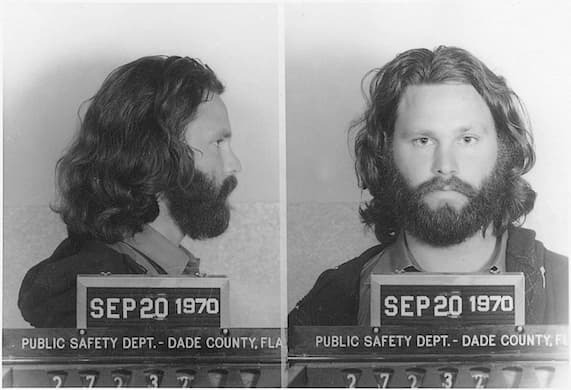

Like Rimbaud, Morrison held back nothing and did not seem to worry that he might use himself up — not only in the frenzy of his stage performances but in brutal clashes with the police, taunting them into beating him up. (Although, as Mr. Batchelor recounts, the cops did not require much prodding from this long-haired hippie-looking provocateur.)

If you are of a certain age, or are a Doors fan, you likely already have the lyrics of “Light My Fire” in mind as you’re reading. Sing along as I tell you how Ed Sullivan’s producer asked the band to change the line, “Girl we couldn’t get much higher.” The band agreed to make adjustments, but then Morrison sang the original line during the live performance, outraging the impresario of American wholesomeness.

Mr. Batchelor shows how improbable the Morrison/Doors story is. It begins with the young Morrison adrift on a beach, where he meets a musician friend who decides to take a chance on the untrained and untested singer. Morrison then did not have much of a voice: It took him a good year or more to sound like a seer, one who came out of the depths, on the band’s debut album.

Exactly what happened on that beach and what to make of the origin story of The Doors — their name taken from Aldous Huxley’s mescaline-inspired book, “The Doors of Perception” — becomes an account of how biographies of mythic figures are made, with Mr. Batchelor coming at the creation legend from as many camera angles as you can imagine being used in a movie.

“Roadhouse Blues” is true to its subtitle: This is biography as cultural history. Morrison’s outrageous behavior only makes sense in the context of the Vietnam protests, and the transgressive record albums of bands like the Rolling Stones. Before “Let It Bleed” was released on November 28, 1969, what pop group would have dreamed up such a hemorrhage of tumultuous feelings? Except for The Doors.

Morrison, in Mr. Batchelor’s telling, needed the orchestration of the times for his poetry to be heard. Although his words did make it to the page and to publication, they cannot compete with his voice backed up by a band who believed they were all equal and took credit together for their creations.

One of the best features of “Roadhouse Blues” is how it ends — not with Morrison’s death and not with the demise of The Doors. (Their music lives on, of course, helped by the release of seemingly endless takes.) Instead, the biographer concludes with a chapter on the burgeoning literature about the band, which serves as an introduction to why it matters.

Yet more is accomplished in that last chapter. Biographers are in the habit of citing their sources without saying that much about what really matters about them and how a reader and biographer can make the best use of them. Too many biographers simply tout their access to primary sources, giving only glancing acknowledgments to their predecessors.

Mr. Batchelor, on the contrary, shows how biography and history are made through memoirs, profiles, and other biographies that are in dialogue with one another — or, better yet, part of a dialectic out of which books like “Roadhouse Blues” emerge. Biography itself, like its subjects, has a provenance, an origin story that few biographers illustrate as well as this one.

Mr. Rollyson deals with the origins and development of biographies in his podcast, “A Life in Biography” https://anchor.fm/carl-rollyson