This Independence Day, New York’s World War I Heroes Are Forgotten in a Transit Museum Office

A memorial to New York City subway employees killed in the Great War was removed from its place of honor at Grand Central Terminal and now languishes in an appointment-only research facility.

As Americans celebrate Independence Day by reflecting on the contributions of past generations, a bronze memorial to New York City subway employees killed in World War I languishes in a Transit Museum office, removed from its place of honor in Grand Central Terminal.

The American Legion and Interborough Rapid Transit Company erected the plaque in June 1939 at the Times Square Station, later moving it near a Lexington Avenue passage. In 2019, the MTA told a licensed tour guide with the city, Kevin Fitzpatrick, that it had been stored in the Transit Museum during renovations.

The memorial plaque is currently situated in the Transit Museum’s Gabrielle Shubert Research Center, which is accessible to the public by appointment only, the MTA told the Sun. Appointments, the Transit Museum notes, “must be scheduled at least two weeks prior to the date of the visit and confirmed at least 48 hours in advance.”

“Independence Day means to me more than what the Founders did in Philadelphia,” Mr. Fitzpatrick, a Marine veteran, told me. “It’s about the whole expanse of our country’s history across 247 years. This small sliver of City history, of 35 IRT workers serving and dying for our country, needs to be remembered.”

Since the renovations were completed, there has been no news on when the plaque might be returned to its place of honor where commuters can see it, though the MTA, tells the Sun that it intends to restore it to public view.

“There are aviators and Harlem Hellfighters named on this plaque,” Mr. Fitzpatrick said. “It’s the only memorial these men have, and the fact that the MTA is doing nothing to get this history brought back is a sad case,” not least because it runs the risk of being lost to thieves hungry for scrap metal.

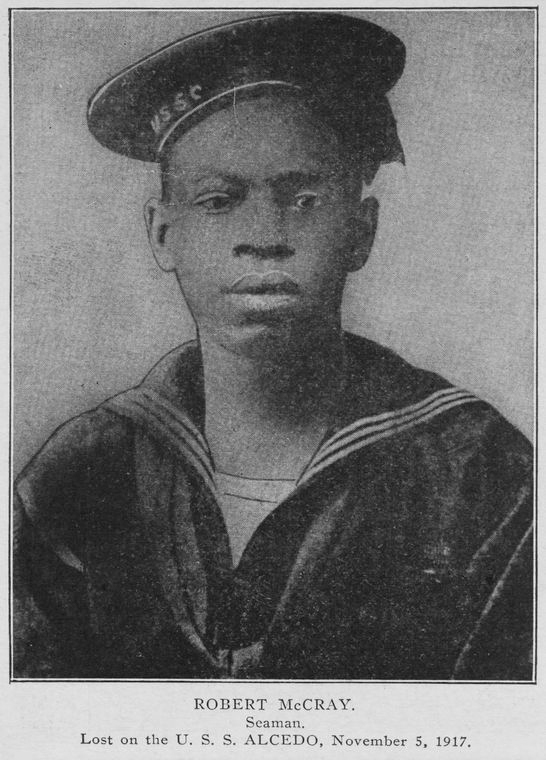

The names on the plaque tell stories of America. A private with the Harlem Hellfighters, James Hamilton, was killed in battle near Romagne. An airman, Wayles B. Bradley, burned to death during training. A Black clerk aboard the U.S.S. Alcedo, Robert McCray, was lost when a U-boat struck.

A seaman, Walter D. O’Connell, died on the U.S.S. Gypsum Queen off Brest. “It is ironic,” Mr. Fitzpatrick says, “that men and women who are subway workers removed a memorial to subway workers killed in WWI. To them, it was just another sign to move, nothing else.”

Sixteen of the fallen, Mr. Fitzpatrick says, remain buried in France, while “their memorial plaque is buried” in an office at “the Transit Museum. That bronze plaque needs to be seen by the public on Independence Day, and every day, inside Grand Central Terminal.”

“We will remember them,” Lawrence Binyon wrote in his poem saluting the war’s fallen. “They went with songs to the battle,” it reads. “They were young, straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow. They were staunch to the end against odds uncounted; they fell with their faces to the foe.”

In this spirit, New York City erected more monuments for World War I than for any other event, as Mr. Fitzpatrick described in our “History Author Show” interview about his book, “WWI New York: A Guide to the City’s Enduring Ties to the Great War.”

When the Americans arrived in France a century ago, they were mindful not only of vanquishing the Central Powers, but of repaying the debt their forefathers owed the nation’s first ally, whose fleet proved crucial to President Washington’s victory at the Battle of Yorktown.

France’s commitment was embodied in their officer, Marquis de Lafayette, on Washington’s staff. In May 1917, the Sun reported on “the wave of enthusiasm for France” a month after America’s entry into the war, describing 200,000 turning out to dedicate a memorial to the marquis in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park.

On July 2, 1917, the Americans marched to Lafayette’s grave in Paris where Colonel Charles Stanton declared, “Lafayette, we are here!” Next came the horrors of the Western Front where the doughboys — refusing to be dispersed to Allied units that doubted their ability to fight alone — announced the nation’s arrival as a world power.

Each generation has had to match the sacrifices of those who fought to secure America’s independence. This July 4th, spare a moment to salute them all, including the Grand Central 35, who died to “make the world safe for democracy,” and earning an honored place in our city.

_______

Correction: The World War I memorial plaque is currently located inside an appointment-only research facility within the Transit Museum’s offices at Brooklyn. An earlier version misstated the current location of the plaque.