Can Trump ‘Nationalize’ Elections?

By THE NEW YORK SUN

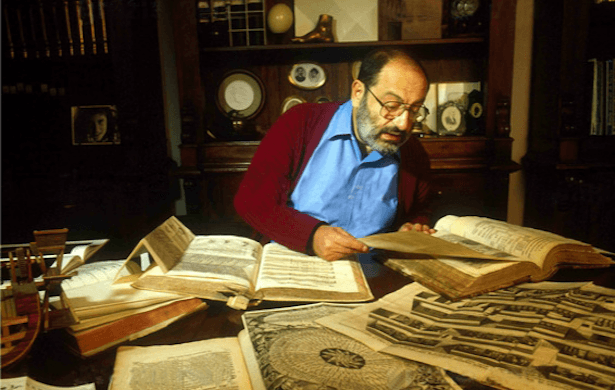

|Best known as the writer of best-sellers, Eco comes across as impish and approachable, a man given as much to extolling the virtues of ‘Peanuts’ as he is to exploring abstruse fields of intellectual endeavor.

By THE NEW YORK SUN

|

By JOSEPH CURL

|

By LAWRENCE KUDLOW

|

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|

By MATTHEW RICE

|

By LUKE FUNK

|

By BENNY AVNI

|

By JOSEPH CURL

|Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.