Toast the Erie Canal, Celebrating 200th Anniversary, for Transforming America and Making New York City a Financial Hub

A triumph of human ingenuity, the waterway demonstrates ‘what could be done by an involved government,’ one historian avers.

Americans’ pockets hold digital devices delivering oceans of information and distractions. Yet another technology that dramatically shaped the nation’s life, and had revolutionary consequences abroad, was a ditch. Raise a glass as the 200th birthday of the Erie Canal is celebrated on Sunday.

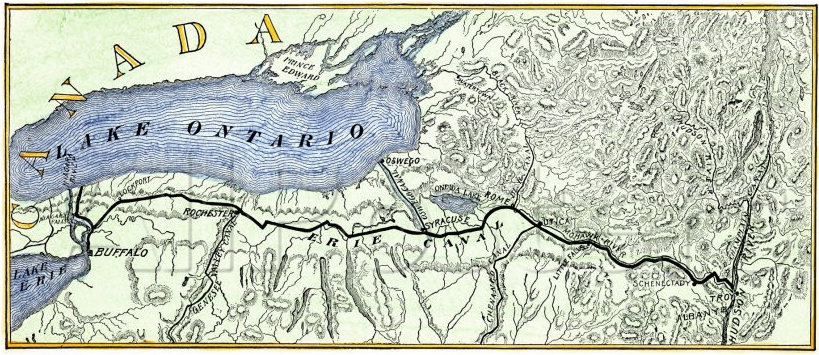

Its 363 miles — the longest previous U.S. canal extended 27 miles — were dug by human muscle in the service of improvised cleverness. Improvised because America had few engineers to create 18 aqueducts, and 83 locks, “to overcome changes in elevation totaling 675 feet.” So writes Daniel Walker Howe in “What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848” in the Oxford History of the United States.

Mr. Howe notes that the canal, “one of the most important achievements of national economic integration,” was wrought — two years ahead of schedule and under budget — not by the national government, but by one state, which the canal would transform into the Empire State.

Work began on July Fourth, 1817. That year, the New York Stock Exchange’s forerunner was founded. The canal “exemplified a ‘second creation’ by human ingenuity perfecting the original divine creation and carrying out its potential for human betterment.”

Soon it was carrying twice the value of goods floating down the Mississippi to New Orleans. Horses or mules that could pull a wagon weighing two tons could, walking on the canal’s towpath, pull a barge weighing 50 tons.

Between Buffalo and Albany, where it met the Hudson River, the canal, 40 feet wide and 4 feet deep, carried traffic at 4 miles per hour. Yet it radically accelerated social change, discomfiting some along its route. The sudden disorienting growth of cities — e.g., Rochester, Syracuse, Utica — stirred religious intensity in what was called a “burned-over” region.

Many New England farms were among the economic, cultural and emotional casualties of the dynamism unleashed by the Erie Canal’s contribution to globalization. Americans were, however, as Mr. Howe says, “a mobile and venturesome people, empowered by literacy and technological proficiency,” welcoming dynamism.

Headlines announced the arrival of Long Island oysters at Batavia, a town in western New York. By 1850, the price of a wall clock had plunged to $3 from $60. Mr. Howe reports: Largely because of lower transportation costs, “changes from the rustic to the commercial that had taken centuries to unfold in Western civilization were telescoped into a generation in western New York state.”

By lessening the commercial and political isolation of prairie farmers, the canal helped to populate the prairies by connecting them with Eastern markets.

And by linking Americans living west of the Appalachian Mountains to the Hudson River, it created New York City as a financial center. One day in 1824, Mr. Howe writes, there were 324 ships in New York harbor. One day in 1836, there were 1,241. Through the city’s port, America exported grain and revolution.

In 1986, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York, speaking at Buffalo, speculated that America’s 19th-century tsunami of immigration was “in considerable proportion” a result of “the huge wave of agricultural exports that began to reach Europe once the railroads reached our Middle West.”

Moynihan cited a historian’s calculation that at least a third of a million European farms “in a long arc from England and Denmark through Prussia on into Russia” were shut down by competition from the American prairies.

Wheat acreage in England alone was reduced 40 percent between 1869 and 1887. The historian wrote: “The small capitalist farmers of North America hacked away at the economic base of the ruling landed classes in Europe more destructively than all the revolutionaries on the continent.”

To mark the canal’s opening, a keg of Lake Erie water was dumped into New York’s harbor — the “wedding of the waters.” The 100,000 — half the city’s population — who celebrated exceeded all prior American gatherings. As Mr. Howe says, the Erie Canal demonstrated “what could be done by an involved government.” The example is still pertinent.

Railroads soon eclipsed the importance of canals, but before they did, in 1849 the federal government granted patent No. 6469 for an invention that facilitated the passage of canal traffic “over bars, or through shallow water.”

The inventor was a former one-term congressman from Sangamon County, Illinois, who promoted canals for developing central Illinois.

Abraham Lincoln could not have anticipated the importance of the Erie Canal supplanting much Mississippi River commercial traffic, and stimulating the Midwest’s population growth.

This changed the primary axis of American commerce from North-South to West-East, fueling Northern economic dynamism, with consequences seen at Appomattox. Some ditch.

The Washington Post