Under Those Trademark Fashionable Hats Was a Woman Both Diplomatic and Tough

Anna Rosenberg was a big deal, usually working behind the scenes until George C. Marshall insisted on her appointment as the Department of Defense’s first female high-ranking official.

‘The Confidante: The Untold Story of the Woman Who Helped Win WWII and Shape Modern America’

By Christopher C. Gorham

Citadel, 384 pages

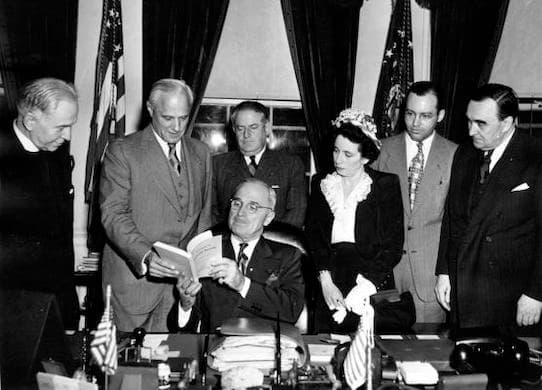

Begin with this biography’s photographs: Anna Rosenberg with Fiorello LaGuardia and Eleanor Roosevelt; in a light tank during her mission in 1944 as FDR’s special representative to the European Theater of Operations; with Generals Omar Bradley and George Patton; with President Truman pinning her with the Presidential Medal of Freedom; staring head-to-head with Senator Lyndon Johnson; with George C. Marshall being sworn in as assistant secretary of defense; in Korea with James A. Van Fleet, commanding general of the U.S. Eighth Army and UN forces; with John F. Kennedy after his Madison Square Garden birthday party.

You get the picture: Anna Rosenberg was a big deal, usually working behind the scenes until George C. Marshall insisted on her appointment as the Department of Defense’s first female high-ranking official. “What can I do?” she asked Marshall. “Everything I do,” he replied, even as he made sure she had an office next to his because he knew the all-male regime would give her a hard time.

Rosenberg had been reluctant to accept Marshall’s offer — not because she feared male chauvinism or the opposition of Senator Joseph McCarthy, who failed to link her with those other Rosenbergs, Julius and Ethel (there was no connection, political or familial), but because she had already sacrificed lucrative business opportunities for low-paying government work and did not crave public attention for her achievements.

This biography contains no photograph of Rosenberg and FDR, even though, as Mr. Gorham amply demonstrates, she was in fact his confidential operative, turning her work in the LaGuardia administration into the model of how to roll out the new Social Security program.

Neither FDR nor Rosenberg ever wanted their closeness to be made public. How close? Late in the biography, we learn that in private she said she had burned FDR’s love letters. Mr. Gorham has worked diligently to uncover what Anna Rosenberg wanted to hide. She left behind no diary and refused to publish a memoir.

It is doubtful that Rosenberg — except for that startling comment about FDR’s love letters — confided in anyone, and even that admission was to a gentleman far from the centers of power, one who did not have the slightest interest in publicizing what she told him.

Rosenberg was a child of Hungarian immigrants with a high school education that equipped her well enough to succeed in the worlds of business and government. Yet like many high achievers without a prestigious degree or family, she was wary of competing at the highest levels with the likes of women such as Francis Perkins, FDR’s secretary of labor and a University of Pennsylvania graduate.

Aside from FDR, Rosenberg’s favorite was Lyndon Johnson — also wary of those “Harvards,” as he called them. Rosenberg and Johnson bonded and battled over defense appropriations, with Johnson calling her the most effective public servant he had ever worked with.

Why was Rosenberg so successful? The short answer is that she was smart and she knew how to be both diplomatic and tough, while wearing her trademark fashionable hats — seeing no contradiction between feminine charm and her prowess as an administrator.

Rosenberg got her start working for local New York City politicians, and then as a mediator between unions and employers, earning the trust of both sides as she worked out solutions they could accept. Nelson Rockefeller counted on her for that negotiating ability on building projects as well as his successful New York gubernatorial campaign in 1958.

Even though John F. Kennedy showed virtually no interest in women’s issues or in employing many women while president, the loyal Democrat Rosenberg campaigned and raised money on his behalf. Mr. Gorham does not say so, but I have to wonder if Kennedy’s keen interest in women as bedmates did not have political repercussions that resulted in a retrograde record in employing women compared to FDR, Truman, and Johnson.

Judging by Mr. Gorham’s biography, Rosenberg never called herself a feminist. She just worked hard to make women and minorities fully employable in the administrations she served. She never gave up on her equal opportunity efforts, or on those flamboyant hats that were her props of power as she made herself the prow of effective government programs.

Mr. Rollyson’s work in progress is “Making the American Presidency: How Biographers Shape History.”