Viewers Beware: Jem Cohen’s New Film, ‘Little, Big, and Far,’ Is Not What It First May Seem

Once an artist trades in duplicity, the trick — and, potentially, the magic — is to sustain the illusion. Here is a lovely film flawed, not fatally but decisively, by its maker’s hubris.

Not long ago in these pages, Carl Rollyson wrote about biographical fiction, a literary genre that allows for wiggle-room between hard-and-fast facts and varying degrees of speculation. A by-product of such ventures is, as Mr. Rollyson noted, incredulousness: “What am I supposed to believe? What is true, what is not?” A new film by Jem Cohen, “Little, Big, and Far,” will likely prompt similar responses from audiences who haven’t read the fine print before sitting down with their tubs of popcorn.

Truth to tell, Mr. Cohen’s film took me aback when the final credits began their roll. Having spent two hours with an Austrian astronomer, his American physicist wife, a British naturalist in Manhattan and her colleague, a young Ecuadorian captivated by the whys-and-wherefores of the heavens, I was flummoxed to learn that these experts in their fields were, to a person, actors. Although the director did tip his hand a few times during the film, his cinematic fudgings weren’t any more egregious than those seen in a typical documentary.

What kind of creature is “Little, Big, and Far?” A fiction that cruises on the conventions of cinéma vérité. Although Mr. Cohen is prone to arty longueurs, his massaging of genres is less contrived than one might fear. He’s an experimental filmmaker of gently stated means who doesn’t begrudge the niceties of character, contradiction, and empathy. “My work has always been based on close observation … [being] a celebration of curiosity and wonder as primal human impulses.” Mr. Cohen does pretty well on realizing his ambitions.

The events in the film center on Frank (Franz Schwartz), a 70-something astronomer, academic, and museum consultant. He’s something of a contrarian, our hero: When we first meet Frank, he’s hard at work on a laptop, but fielding phone calls on an answering machine or, as a frustrated co-worker has it, “this ancient device.”

Frank is bedraggled in appearance, philosophical in mien, and over-the-hill in terms of his professional life. In a voiceover narration, we listen to him repeatedly extol the grandeur of the universe as well as its attendant mysteries. A free jazz album by John and Alice Coltrane, “Cosmic Music,” is a touchstone that exemplifies Frank’s notion of the universe: “chaos that really isn’t chaos.” All the while, Mr. Cohen’s camera scans Frank’s Viennese apartment with its clatter of photos, books, posters, and other souvenirs of a life long-lived.

“Little, Big, and Far” doesn’t unfold so much as accumulate — at least during its first hour. The rhythm of the film is meditative, having the cadence of a conversation that has been thoroughly mulled, if not altogether resolved. We meet Sarah (Jessica Sarah Rinland), a pensive young woman whose study of biology leads her to wander the galleries of Manhattan’s Museum of Natural History. In a letter sent to Frank, she muses about the “currency and maybe necessity” of melancholy upon considering the institution’s museological imperative. It’s an incisive bit of writing on Mr. Cohen’s part.

As is a story related by Frank’s wife, Eleanor (Leslie Thornton), a professor at an unnamed Texas university — a gig that is, presumably, plummy enough to warrant a bi-continental marriage. With her dry wit and unaffected tone, Ms. Thornton relates stories of the recent eclipse as we watch a raft of curiosity seekers setting up their folding chairs in a shopping mall parking lot. Later, Eleanor recounts a conversation with a cocktail waitress about how “something unseen keeps the galaxy together.” The waitress responds in a manner that has the tang of real life. Mr. Cohen has an appreciative ear for the vernacular.

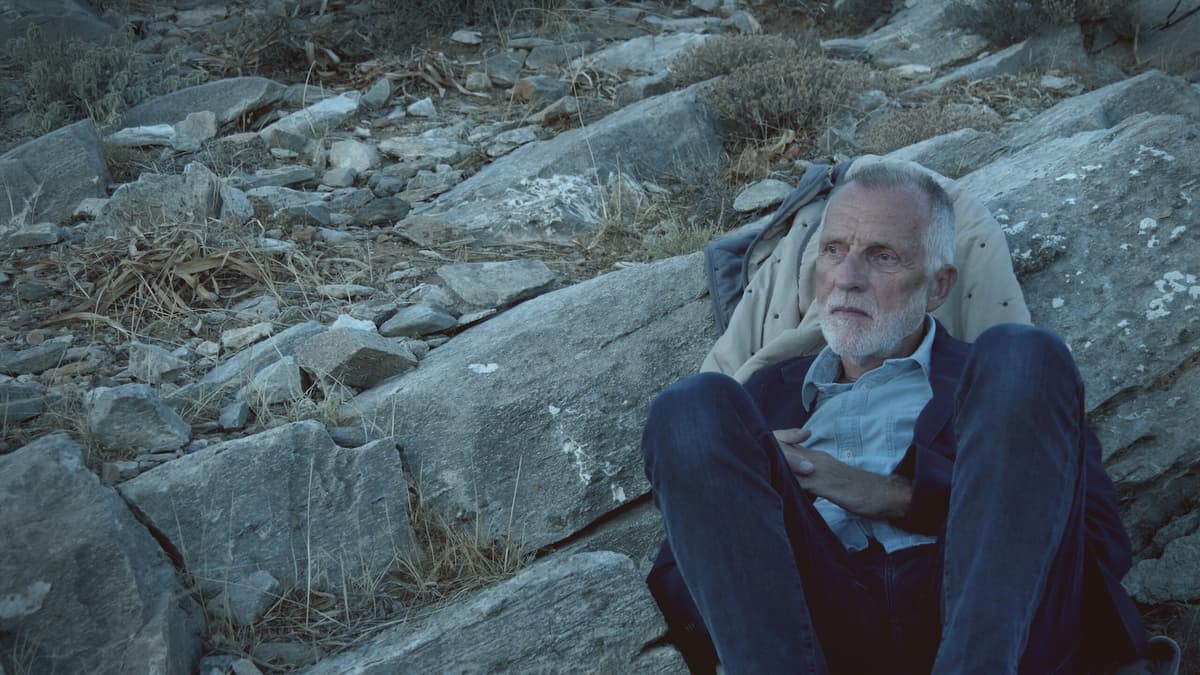

We follow Frank as he travels to Greece, meets up with Sarah, and then goes on an off-the-cuff trip to the island of Tinos. Mr. Cohen takes a similar byway when he forsakes a multiplicity of characters to concentrate on an increasingly discursive Frank. There are lovely moments in this Grecian sojourn — we meet a helpful pharmacist and an old man with peculiar notions about the movement of the stars — but then Mr. Cohen the polemicist up-and-takes precedence over the Austrian eccentric he’s tenderly put into shape. As a result, “Little, Big, and Far” loses momentum and, to some extent, purpose.

Once an artist trades in duplicity, the trick — and, potentially, the magic — is to sustain the illusion. Here is a lovely film flawed, not fatally but decisively, by its maker’s hubris.