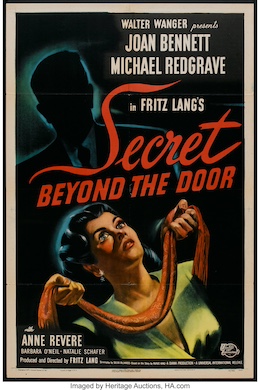

Was Fritz Lang Attempting To Outdo Alfred Hitchcock With ‘Secret Beyond the Door’?

While ‘Secret’ is a fairly blatant riff on Hitchcock’s ‘Rebecca,’ the melodrama inherent in Lang’s picture is, at least for those with a taste for noir at its most flamboyant, irresistible.

While we’re all conversant with the notion that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, did you know that an Irish playwright, George Bernard Shaw, added a postscript to the bromide? Imitation, he also noted, is “the sincerest form of learning.” Shaw’s addendum was brought to mind upon watching “Secret Beyond the Door” (1947), a Blu-Ray edition of which has been released by Kino Lorber.

First, the imitation: “Secret Beyond the Door” is a fairly blatant riff on “Rebecca” (1940), Alfred Hitchcock’s take on the Daphne du Maurier novel. As with the earlier film, a beautiful young woman marries a widower given to moody and morbid reveries. He lives in a palatial manor with rooms in which our heroine is welcome — and one to which she is not. In the end, a consuming blaze brings the proceedings to an end.

Now, about the learning: The obvious takeaway is that a hit movie begets, if not necessarily sequels, then variations on a theme that hope to cash in on its success. Hollywood has rarely thought twice about shameless mercantilism. Another lesson is that each generation, at one point or another, is challenged and sometimes bested by a younger generation.

Granted, the Austrian-born filmmaker behind “Secret,” Fritz Lang (1890-1976), was only nine years older than Hitchock, but, in pop culture terms, a decade might as well be an eternity. Lang could not have helped but notice that his fellow European was making significant inroads on his turf — that is to say, movies canted toward the fatalistic, the fantastic, and the underhanded. Lang, in so many words, might’ve been trying to one-up “Rebecca” when he took on the assignment.

Or maybe he just wanted to go four-for-four with actress Joan Bennett. Lang first worked with Bennett on “Man Hunt” (1941), a ramshackle anti-Nazi thriller, and, later and more memorably, on “The Woman in the Window” and “Scarlet Street” (both 1944). The latter two did well enough at the box office to prompt Bennett and Lang to give it another go with “Secret Beyond the Door.” Bennett had a financial stake, as it was made under the imprimatur of her company, Diana Productions.

“Secret Beyond the Door” met with critical equivocation and disappointing box office receipts, sinking Diana Productions, where things weren’t great before the film hit theaters. Bennett found plenty to bristle about in Lang’s demands, especially that she do her own stunts during the picture’s fiery denouement. Bennett has been quoted as saying that the film was “an unqualified disaster.” She never worked with Lang again.

Bennett was unfair in her estimation. “Secret Beyond the Door” is less disastrous than it is preposterous. Even by the generous standards of disbelief that are often required of movie-goers out for a thrill, the plot takes several wild turns as Celia (Bennett) comes to grips with new husband Mark (Michael Redgrave) and his many secrets. Chief among them is his condescending teenage son David (Mark Dennis). Mark’s cagey sister Caroline (Anne Revere) is relatively straightforward, but not Miss Robey (Barbara O’Neil), the house secretary who skulks around the premises wearing a partial veil.

Then there’s the sizable wing of the Lamphere mansion dedicated to Mark’s recreations of murder scenes. Celia’s husband, you see, has a theory about the psychological pressures that architecture can bring to bear on its occupants. As he shepherds a group of guests through these chambers, Celia becomes increasingly incredulous about Mark’s hobby. When he forbids anyone from entering the final room — well, Celia just can’t let some secrets be, can she?

The melodrama inherent in Lang’s picture is, at least for those with a taste for noir at its most flamboyant, irresistible. Working with cinematographer Stanley Cortez, who had performed similar duties for Orson Welles in “The Magnificent Ambersons” (1942), Lang created a 19th-century dreamscape that is, in equal parts, pure Expressionism and unapologetic fashion shoot. Costume designer Travis Banton brought his A-game to Bennett’s wardrobe: She looks exquisite throughout. Cortez lights her with something approaching reverence.

The Freudian profundities peppering the screenplay will likely occasion titters from contemporary audiences, and the script contains byways, rationales, and conveniences that have, at this date, become predictable. Still, those who give themselves over to “Secret Beyond the Door” will realize that its unremitting extravagance waylays its considerable lapses in logic. Here is an odd creature worth rediscovering.