What Might Be the Consequences If North Korea Tests a Nuclear Weapon?

Kim Jong-un has failed to test an A-Bomb in more than five years.

Tough talk about the punishment that awaits North Korea if Kim Jong-un orders another nuclear test provokes a tough question: What do leaders in Washington, Tokyo, and Seoul have in mind beyond more sanctions and more war games involving American and South Korean troops?

The Pentagon’s “national defense strategy” says “any nuclear attack” by the North would “result in the end of that regime” and “there is no scenario in which the Kim regime could employ nuclear weapons and survive.”

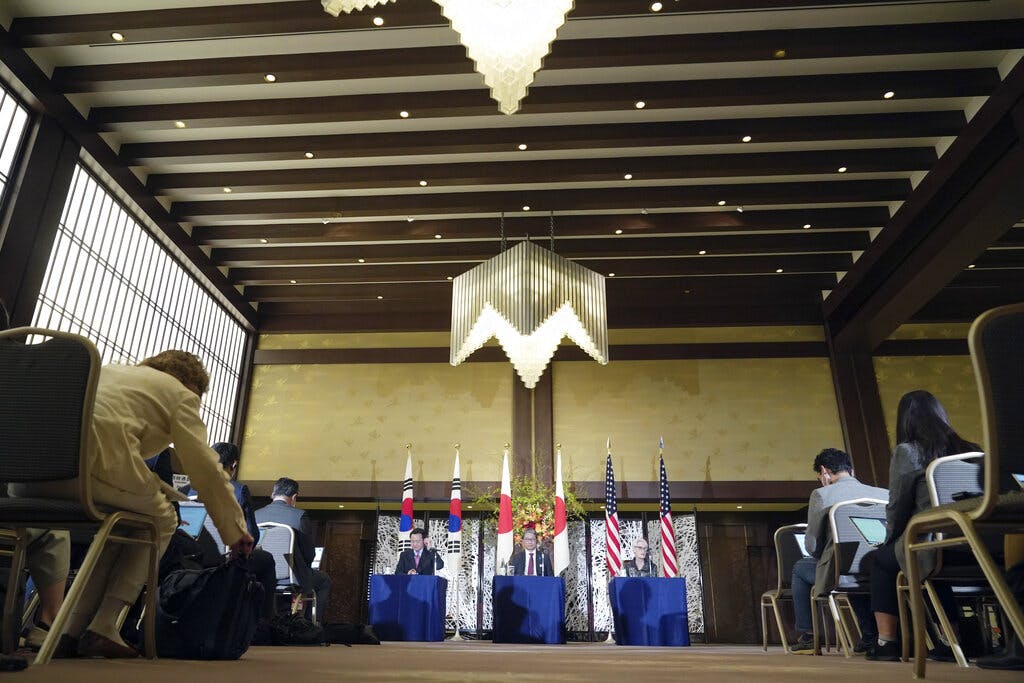

That rhetoric, however, avoids the question of how Washington and its Northeast Asia allies would respond to what would be North Korea’s seventh nuclear test, its first in more than five years. American, Korean, and Japanese policy-makers, meeting in Tokyo, warn of the dangers but offer no clue of what to do.

All our deputy secretary of state, Wendy Sherman, in Tokyo with her counterparts from Japan and Korea, could think of to say is that another North Korean nuclear test would be “reckless and deeply destabilizing.” South Korea’s vice foreign minister, Cho Hyun-dong, said “an unparalleled scale of response would be necessary.”

All agreed on that, he said, while offering no details. Back at the State Department in Washington, spokesman Vedant Patel spoke of “tools at our disposal” to “hold” the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea “accountable.” Great, but what tools?

“That language suggests something important, substantial, painful, and new is in the cards,” says a former senior American diplomat in Seoul, Evans Revere. “The diplomatic, political, and economic toolkit, including the use of covert measures, that we could use to turn up the heat on North Korea is by no means exhausted.”

Short of ordering strikes on North Korea’s nuclear and missile complexes, however, the inventory of possible responses does not appear to go much beyond whatever Washington and its allies have been doing for years.

Among other things, Mr. Revere cited “new military deployments,” “new sanctions,” “new and/or larger-scale military exercises” and “other measures against third-country firms, including banks and other entities that directly or indirectly support North Korea.”

He also suggested encouraging other countries to “consider closing North Korean diplomatic missions and trading firms,” further isolating a regime that is already isolated from most of the rest of the world.

A retired army colonel, David Maxwell, who served five tours in Korea, is no less compromising but takes a somewhat different approach. “The key is to make Kim Jong Un understand his strategy is failing,” said Colonel Maxwell, now a senior fellow with the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

That advice may not be as soft-line as it sounds. In the process, said Mr. Maxwell, you show Mr. Kim that American and South Korean forces are ready for anything. “You do that by continuous training and deployment of strategic assets.” Above all, he added, “There can be no concessions whatsoever” lest Mr. Kim “assesses his strategy a success.”

A former CIA analyst and long-time Korea expert at the Heritage Foundation, Bruce Klingner, noted one significant change that could make a difference. The conservative South Korean president, Yoon Suk-yeol, “has already demonstrated a greater willingness to respond to North Korean provocations, to impose sanctions, and to criticize North Korean human rights violations” than did his predecessor, the leftist Moon Jae-in.

“The change in administration in both Washington and Seoul allowed for a resumption of combined military exercises after a four year hiatus,” he said.

“Another North Korean nuclear test will lead to US rotational deployment of strategic assets, including bombers, dual-capable aircraft, and carrier strike groups; extensive allied military exercises; issuing of new sanctions against North Korean entities; and greater trilateral security cooperation amongst Seoul, Tokyo, and Washington,” he said.

Mr. Klingner was “less certain,” however, as to whether Seoul would “integrate its missile defense system into the more comprehensive allied system, or whether Washington will finally impose significant sanctions on Chinese banks and businesses facilitating North Korean violations of UN resolutions.”

Mr. Maxwell adds one more recommendation – that of emphasis on “human rights atrocities.”

As a matter of policy, he said, both Washington and Seoul when they “mention north Korea nuclear, missile, and military threats” should also “remind the Korean people in the north and the international community that their human rights are being denied because Kim deliberately prioritizes nuclear and missile development over the welfare of the people.”