What Was Blaxploitation? New Book Charts the Influential Genre’s Highs and Lows

Like Impressionism, Cubism, and, to a certain extent, jazz, Blaxploitation was a calumny that its practitioners took on as a badge of honor. Who doesn’t enjoy thumbing one’s nose at presumed arbiters of moral virtue?

‘Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras: A History of Blaxploitation Cinema’

By Odie Henderson

Abrams Press

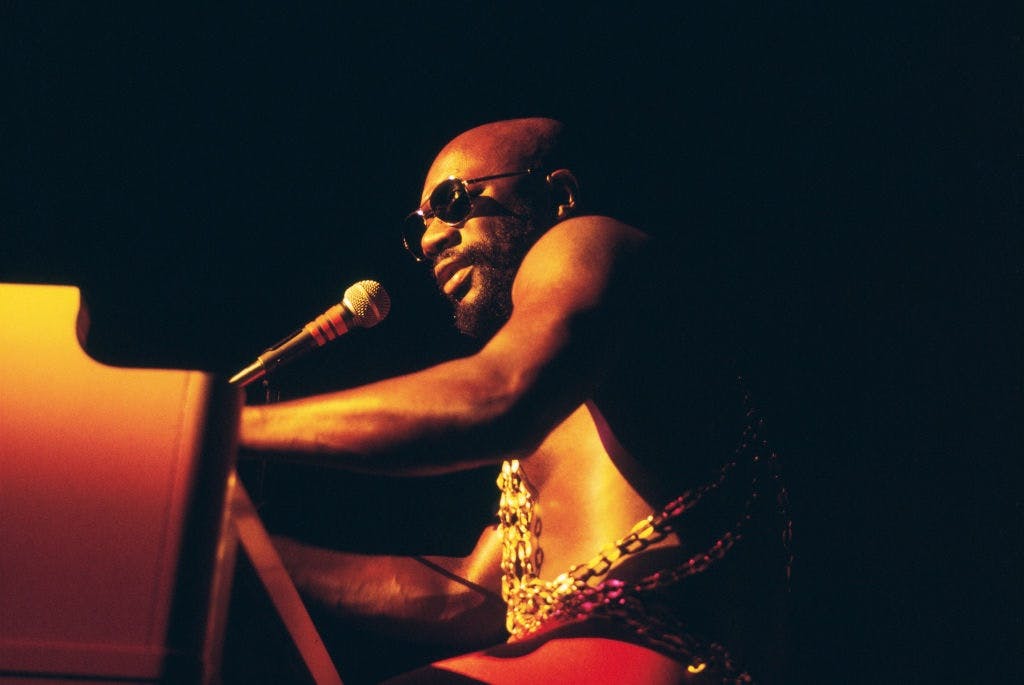

Toward the back of “Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras: A History of Blaxploitation Cinema,” a new book by a Boston Globe film critic, Odie Henderson, there is a list of the 10 best songs associated with the genre. The performers responsible for them are a veritable who’s-who of post-war popular music: Levi Stubbs of the Four Tops, Marvin Gaye, James Brown, Martha Reeves, Curtis Mayfield, and Isaac Hayes.

The latter’s “Theme From Shaft” is among the most distinctive earworms extant, an inescapable cultural landmark on the scale of Humphrey Bogart’s lisp, Marilyn Monroe’s airborne dress, and the Statue of Liberty’s torch. “Oh, come on,” Mr. Henderson writes, “you knew this was number one.” Whereupon he mentions its status as winner of the 1972 Oscar for Best Original Song. It also won a Grammy for Best Original Score and was later paid homage to on “Sesame Street” by, of all muppets, Cookie Monster.

That funky paean to the pleasures of macaroons, “Cookie Disco,” occurred just at the cusp at which the era of Blaxploitation was drawing to a close. What brought about the end of this “freewheeling, often shameless, and wildly influential cinema genre?”

Mr. Odie notes that Elvis Mitchell, a former film critic at the New York Times, places blame for the demise on the poor box office response to the pricey re-envisioning of “The Wizard of Oz,” “The Wiz” (1978). It’s not an unreasonable thesis: “Hollywood,” director Melvin Van Peebles noted, “has an Achilles’ pocketbook.”

Could it have been television, though? Some of the highest-rated television shows of the time featured African-American casts, including “Good Times,” “Sanford and Son,” and “The Jeffersons.” Then there was the game-changing mini-series “Roots”: “a ratings blockbuster so potent that its viewing numbers … have never been repeated.” Why pay good money to attend the local movie palace when one can stay at home and be entertained for free?

Standards of culture evolve and historical trends peter out. A change of societal mores can account for the deviation in the predilections of various audiences. Blaxploitation pictures had become “very cheap cash grabs” and were reaching a terminus of energy and inspiration. Yet the marketplace is nothing if not absorbent. The genre faded, but its influence runs deep. Rap music is inconceivable without Blaxploitation, as are talents as notable as Spike Lee, John Singleton, and Quentin Tarantino.

What was Blaxploitation? The term originated from circumstances that were far from commendatory. In 1972, a former head of the Hollywood branch of the NAACP, Junius Griffin, formed the “Coalition Against Blaxploitation” in response to the success of movies like “Cotton Comes to Harlem” (1970), “Shaft” (1971), and “Superfly” (1972). He claimed that such films, with their emphasis on sex, sensationalism, drugs, and violence, were a “form of cultural genocide.”

Like Impressionism, Cubism, and, to a certain extent, jazz, Blaxploitation was a calumny that its practitioners took on as a badge of honor. There are few things more validating than thumbing one’s nose at presumed arbiters of moral virtue.

This is, in significant part, Mr. Odie’s rationale for putting a spotlight on what “many consider a disreputable series of films.” By keying into the country’s troubled history on racial matters, as well as the imperatives of popular culture, he locates the sociological worth of the films as markers of Black autonomy, as a forum for how marginalized people can “win at the end.”

If that all sounds heady, rest assured that Mr. Henderson may be a cineaste, but he’s also a fan. One of the pleasures of “Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras” is how deftly he navigates between matters of cinematic quality and the wiles of personal taste: “For better and for worse, Black people were front and center in Blaxploitation, playing the heroes and starring in their own tales.”

As he wends his way through the bumpy history of Blaxploitation, Mr. Henderson is upfront about the limitations of many of the films under discussion. When writing about the infamous “Mandingo” (1975), he states that it “should be evaluated only for what it is: TRASH!” Whereupon the author pauses, takes a beat, and exclaims “And it’s good trash, too!” We can disagree about Mr. Henderson’s opinion even while admiring his candor and enthusiasm.

“A History of Blaxploitation” isn’t encyclopedic in its focus, but Mr. Henderson is thorough in delineating how the films were made, the stories they tell, and their subsequent reception by audiences, critics, and whoever else put in their two cents.

My lone complaint is that the author is prone to identitarian nostrums that are, alas, the lingua franca of a generation. Still, I have to thank him for mentioning grindhouse favorites from my misspent adolescence — those would be “The Twilight People” (1972), “Sssssss” (1973), and “The Beast Must Die” (1974) — and for providing a resource that is as unaffected as it is informed.

Odie Henderson will be at the IFC Center February 5 for a conversation and book-signing after the 7 p.m. screening of ‘Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song.’