While Hollywood and Utah May Not Sound Like Much of a Match, the Two Have a Long History in Film

The author of ‘When Hollywood Came to Utah’ is a genial guide through terrain that is bumpy both geologically and artistically. He posits the arrival of moviemakers as the fourth ‘invasion’ by forces outside the Mormon enclave.

‘When Hollywood Came to Utah’

By James V. D’arc

Gibbs Smith

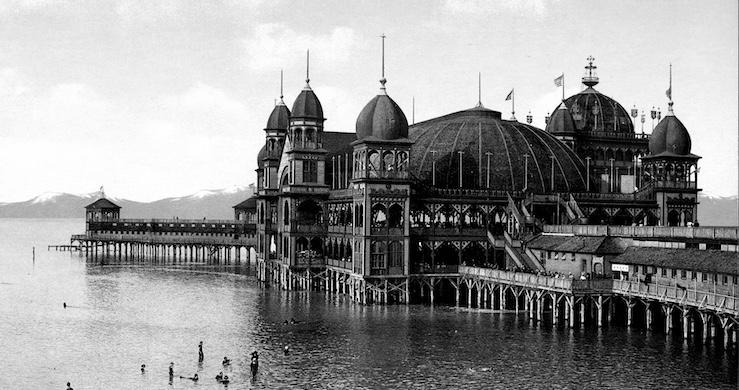

Among the unintended consequences of the cinematic arts is that people, places, and things can be recorded and, as such, immortalized independent of historical initiative. Take, for instance, Saltair, the ill-fated resort situated on the southern shore of the Great Salt Lake.

As proposed, the Saltair Pavilion — a joint venture of the Mormon Church and the Salt Lake, Garfield and Western Railway constructed in 1893 — was the Mountain West’s answer to Coney Island. Over the years, repeated fires, demographic shifts, and the ebb-and-flow of the surrounding water proved antithetical to its sustained success as a commercial venture.

“The Great Saltair” is extant to this day — a bevy of DJs and heavy metal bands will be playing there this summer — but during the time I was growing up at Salt Lake City the site was an abandoned hulk whose grandiose promises of fun and leisure had bitten the dust, making it a veritable ghost town. A maker of educational and industrial films, Herk Harvey, thought along the same lines when driving through Utah sometime in the early 1960s. He went on to make a decrepit Saltair the centerpiece of his one and only feature film, “Carnival of Souls” (1962).

That cult horror favorite is but one of the hundreds of entertainments that have been filmed in the Beehive State. Toward the end of the book “When Hollywood Came to Utah,” you’ll find a daunting list of theatrical films and television programs that have employed the state’s distinctive topography and, perhaps as important, its distance from meddlesome studio execs.

A television writer and producer of the hit series “Touched By An Angel,” Martha Williamson, extolled filming in-and-around Utah’s state capitol because “nobody wanted to fly to Salt Lake on a whim … no one ever came to fix a problem.”

“When Hollywood Came to Utah” was originally published in 2010 and now appears in a new edition as a means of celebrating the centennial of movie-making within the state. A former curator of the Motion Picture Archive at the Harold B. Lee Library at Brigham Young University, James V. D’Arc, has updated his text with additional chapters covering recent Disney productions, “High School Musical” (2019), the television series “Yellowstone” (2018-), and a yet-to-be-released Kevin Costner feature, “Horizon: An American Saga” (2024).

Mr. Costner contributes the book’s introduction, but I daresay the celebrity who is most associated with Utah is Robert Redford, who had a home at Provo Canyon a good decade-and-a-half before establishing the Sundance Film Festival at Park City in 1978.

Taking regular jaunts through the state’s southern reaches during the 1960s, Mr. Redford “always liked the area very much … and saw early on that it had great potential for filmmaking.” It was because of his pull that much of “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969) was filmed at Zion National Park. Other Utah-based Redford vehicles included “Jeremiah Johnson” (1972) and “The Electric Horseman” (1979).

The first picture filmed in Utah, a Tom Mix vehicle titled “The Deadwood Coach” (1924), has been lost to history. Other movies filmed in Utah are better lost to memory, like “The Conqueror” (1956), the infamous outing in which John Wayne portrayed Genghis “I conquer like a barbarian” Khan.

The same year saw the release of one of Wayne’s best pictures, John Ford’s “The Searchers.” San Juan County, the home of Monument Valley, is the locale for more than a few classic Ford Westerns, including “Stagecoach” (1939), “My Darling Clementine” (1946), “Fort Apache” (1948), and “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon” (1949).

Mr. D’Arc is a genial guide through terrain that is bumpy both geologically and artistically. He posits the arrival of moviemakers to Utah as the fourth “invasion” by forces outside the Mormon enclave, the first three being interlopers prompted by the Gold Rush; the U.S. Army as ordered by President Buchanan to quell a nonexistent rebellion; and the merging of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads.

On the whole, the good people of Utah have proved amenable to the incursion of Left Coast wheelers-and-dealers. Mr. D’Arc quotes a Moab farmer regarding these out-of-state creative types: “They don’t take anything but pictures and don’t leave anything except money.” The history of this take-and-leave is diligently set out in this handsomely mounted trove of statist pride.