Santa Monica Establishes $3.5 Million Reparations Fund Despite ‘Dire’ Financial Outlook

By LUKE FUNK

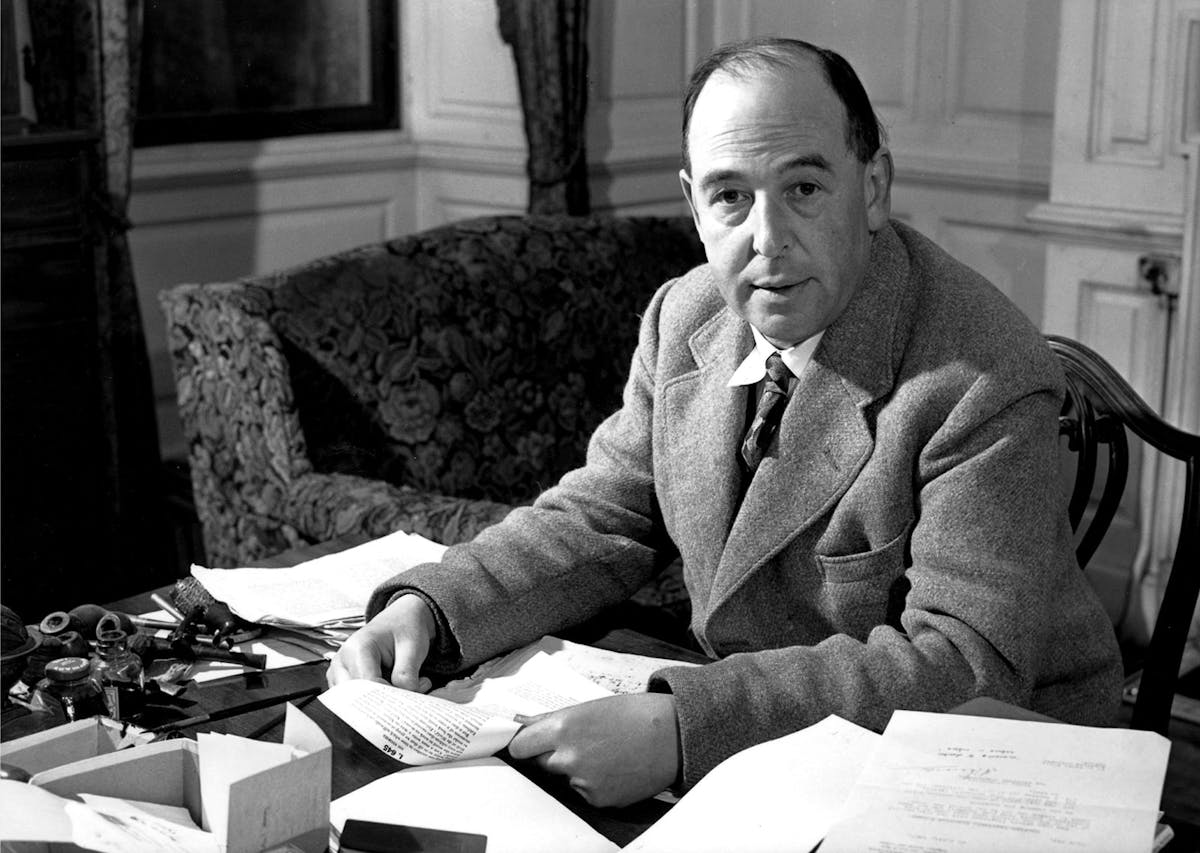

|Jason M. Baxter describes Lewis as a man who ‘read fourteenth-century medieval texts for his spiritual reading, carefully annotating them with a pencil; who summed himself up as chiefly a medievalist.’

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By LUKE FUNK

|

By MATTHEW RICE

|

By DONALD KIRK

|$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.