Kim Jong Un Glorifies North Korean Lives Lost in Ukraine War at Opening of Luxury Apartment Complexes at Pyongyang

By DONALD KIRK

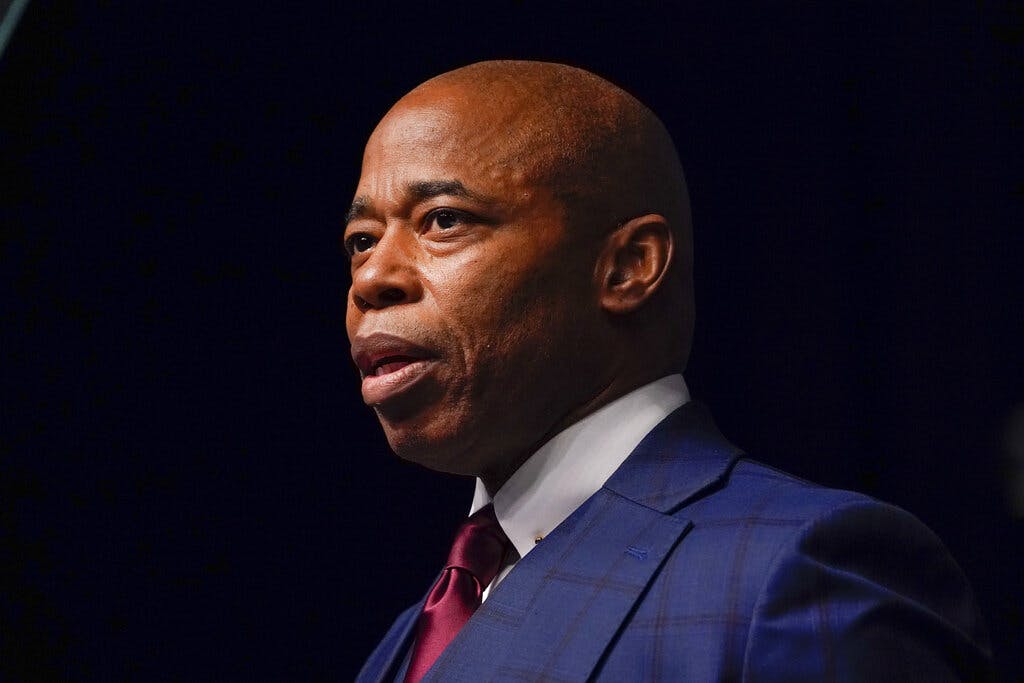

|The approach to subway safety lends key insights into his philosophy for policing in New York City.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By DONALD KIRK

|

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By GEORGE WILLIS

|