With Monsters Everywhere in This Age of Biography, What To Do?

Some will cancel the artist, to use the current cant; others will continue looking at the artist and the work, and Claire Dederer tries to understand why.

‘Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma’

By Claire Dederer

Knopf, 288 pages

Alfred Tennyson remarked that he was grateful not to know very much about Shakespeare’s life. Biography, in other words, did not spoil an appreciation of the plays and poetry.

What would Tennyson have done if he had suddenly been presented with a cache of Shakespeare’s letters? Would he have read them? Or would he destroy the correspondence?

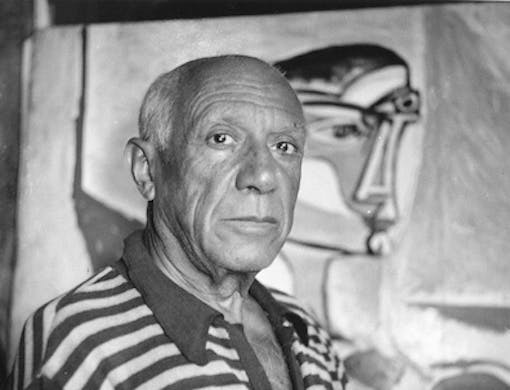

What we learn about an artist, Claire Dederer argues, creates a stain on the artist’s work. If we learn that the artist is a monster — that like Picasso, say, he put out a cigarette on his female lover’s face — can we ever look at the artist’s work without seeing that stain?

Some will cancel Picasso, to use the current cant; others will continue looking at him and his work, and Ms. Dederer tries to understand why.

The author makes her question personal. She adores the films of Roman Polanski, who raped a 13-year-old girl. She has deep reservations about Woody Allen and cannot get Soon-Yi out of her mind.

Ms. Dederer does not try to look away from, or rationalize, Polanski’s monstrous behavior, but she finds so much of value in his films that she has to keep watching. If Woody Allen does not get a full pass from Ms. Dededer, it is because she believes his depravity deforms “Manhattan” but does not disable “Annie Hall.”

Ms. Dederer includes many other examples of artists, such as Doris Lessing and Miles Davis, and canvases the range of reactions others have expressed about these artist/monsters who abandoned children and abused lovers.

I kept copying passages from this supple book that expressed the nuances of the love/hate relationship with artists in this Blake Bailey world where biographers, as much as their subjects, may be canceled for their misdeeds: “We live in a biographical moment, and if you look hard enough at anyone, you can probably find at least a little stain.”

“Why should I be deprived of Chinatown or Sleeper?” Ms. Dederer asks: “This tension—between what I’ve been through as a woman and the fact that I want to experience the freedom and beauty and grandeur and strangeness of great art—this is at the heart of the matter. It’s not a philosophical query; it’s an emotional one.”

“Consuming a piece of art is two biographies meeting: the biography of the artist that might disrupt the viewing of the art; the biography of the audience member that might shape the viewing of art. This occurs in every case.”

And here’s a heartbreaker: “There is a special human thrill—perhaps a female thrill—in locating the tender heart of the brute.” Sylvia Plath said as much.

Gradually, Ms. Dederer’s implicates not only herself in her attachment/avoidance of monsters but the very history of art: “What do we do with the art of monsters from the past? Look for ourselves there—in the monstrousness. Look for mirrors of what we are, rather than of evidence for how wonderful we’ve become.”

In effect, Ms. Dederer argues we have no right to think of ourselves as better than the artists who have been reviled, past or present. We are not, contrary to the liberal dogma she challenges, getting better.

Which is to say Ms. Dederer approaches works of art and artists with great humility, seeing in herself some of the monstrousness that has been projected onto the artists, who may deserve opprobrium but who will continue to have their devotees.

One reviewer has complained that by the end of the book the word monster has become so elastic that it loses all meaning. But that is sort of the point. In the Age of Biography, monsters are everywhere.

Have you seen “The Wife,” a film about the monster a Nobel Prize winner (Jonathan Pryce) and his wife (Glenn Close) are hiding? An irksome biographer asking uncomfortable questions and making upsetting comments exposes the “real” author of the Nobelist’s work.

Clair Dederer’s book is like that movie: It nags at you just as she nags at herself, refusing calls to be “objective,” calls that are — though Ms. Dederer never dares to say so — a little monstrous in themselves.

Mr. Rollyson is the author of “Pablo Picasso: A Biography for Beginners” and “A Higher Form of Cannibalism?: Adventures in the Art and Politics of Biography.”