At Dizzy’s Club, Singing So Vivid It Feels as If You’re Part of the Action

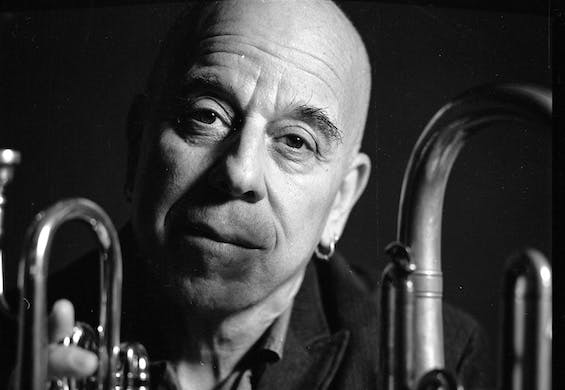

The formidable Catherine Russell is but one of the highlights of the latest run by the prolific Steven Bernstein and two of his many different ensembles.

Steven Bernstein’s Millennial Territory Orchestra & Sex Mob

Dizzy’s Club, Jazz at Lincoln Center

Through October 5

Last night, I went to my girlfriend’s house and she started singing as soon as she opened the door:

“Looka here, Daddy, I want to tell you, please get out of my sight

I’m playin’ quits now, right from this very night

You’ve had your day, don’t sit around and frown

You’ve been a good old wagon, Daddy, but you done broke down.”

Needless to say, I was surprised — stunned even — but before I could respond, she continued:

“When the sun is shinin’, it’s time to make hay

Automobiles operate, you can’t make that wagon pay

When you were in your prime, you love to run around

You’ve been a good old wagon, honey, but you done broke down.”

It was at about this time that I snapped out of it and remembered I was actually in Dizzy’s Club, listening to Catherine Russell singing with Steven Bernstein and his Millennial Territory Orchestra. “Good Ole Wagon” is a 1925 song by Bessie Smith that I know very well. Still, Ms. Russell sings it so vividly that she places you in the middle of the action — especially when surrounded by the vivid musical colors of the MTO. That particular combination is a kind of “augmented reality” unto itself.

I grew up with that record, as well as Dinah Washington’s 1957 version, and even a vaudeville song from 1910 with the same title and sentiment, recorded by phonograph pioneer Len Spencer. Yet hearing Ms. Russell sing it on Tuesday evening made me notice certain aspects I had never thought about before, starting with the notion that it’s a song about technical transition. By the 1920s, wagons were yesterday’s news. The changeover to cars and trucks was already complete; everybody in 1925 would have known what it meant to describe a man as an “old wagon.”

Then, too, it was also a sly reference to the process of aging; on Tuesday, Mr. Bernstein launched a three-night run at Dizzy’s in celebration of his 62nd birthday. (There’s a lot of that going around.) Mr. Bernstein is so prolific and has so many different ensembles, two of which are performing during this run, that every time he plays a major New York venue, he customarily has a new album to launch. This time, though, he was content to play music from the four sets that he released during the nadir of the pandemic in 2021 and 2022, which he has categorized as his “Community Music” series.

On Tuesday, the Millennial Territory Orchestra began with a piece that might be described as a blues overture, encompassing three different themes. He started with the venerable “St. Louis Blues,” more than 110 years old and counting, and then moved on to blues numbers from two different but closely related musical genres, “Rusty Dusty Blues,” from the songbook of R&B legend Louis Jordan, and a sparsely titled melody that he announced as “Blues #1,” which he attributed to a modern jazz pianist, Herbie Nichols.

Fifteen minutes or so in, after his solo on slide trumpet and others by clarinetist Doug Wieselman, violinist Charlie Burnham, and tenor saxophonist Peter Apfelbaum, he closed this sequence with a reprise of W.C. Handy’s iconic tune.

For the rest of the first set, Mr. Bernstein focused on the six tunes that comprise “Good Time Music,” and they all spotlight the formidable Catherine Russell. Having already written about this album at length, let me add that it remains one of my favorites of the 21st century, a masterful statement about the nature of blues drawing on songs from across the decades and subgenres of American music.

It’ll take more time and more columns to delineate the value of the other three “Community Music” albums, but the entry in this quartet that stands out as most different is “Manifesto Of Henryisms.” Recorded shortly before the pandemic, the band here is the Hot 9, which Mr. Bernstein co-led for roughly 10 years with a late New Orleans keyboard avatar, Henry Butler. Whereas the MTO at times seems to be trying — and succeeding — in addressing the whole of jazz, the Hot 9 is somewhat more generationally and geographically specific.

In honor of the much-missed Butler, the music here is slanted toward Crescent City piano, with John Medeski, who previously teamed with Mr. Bernstein’s quartet Sex Mob for a memorable album, guesting throughout on keyboards. The Hot 9 start with Jelly Roll Morton’s “Black Bottom Stomp” in a vigorous twobeat, and move on to “Booker Time,” Butler’s homage to James Booker, as well as Fats Domino in “Josephine.”

“Henryisms” ends with another piece by a great pianist, a very thorough rewrite of Duke Ellington classic, “Diminuendo & Crescendo in Blue.” At Dizzy’s and on “Good Time Music,” Mr. Bernstein also nodded in the direction of Dr. John with Earl King’s “Come On,” a.k.a., “Let the Good Times Roll,” which boasts a highly affirmative vocal by Ms. Russell.

This brings us to a somewhat curious point: It’s clear that pianists were and are a key part of the New Orleans jazz experience, but the street parade also remains one of the most important venues for the music. Pianists in a parade? How’s that going to work? Aha, I guess us old wagons are still good for something.