Can Trump ‘Nationalize’ Elections?

By THE NEW YORK SUN

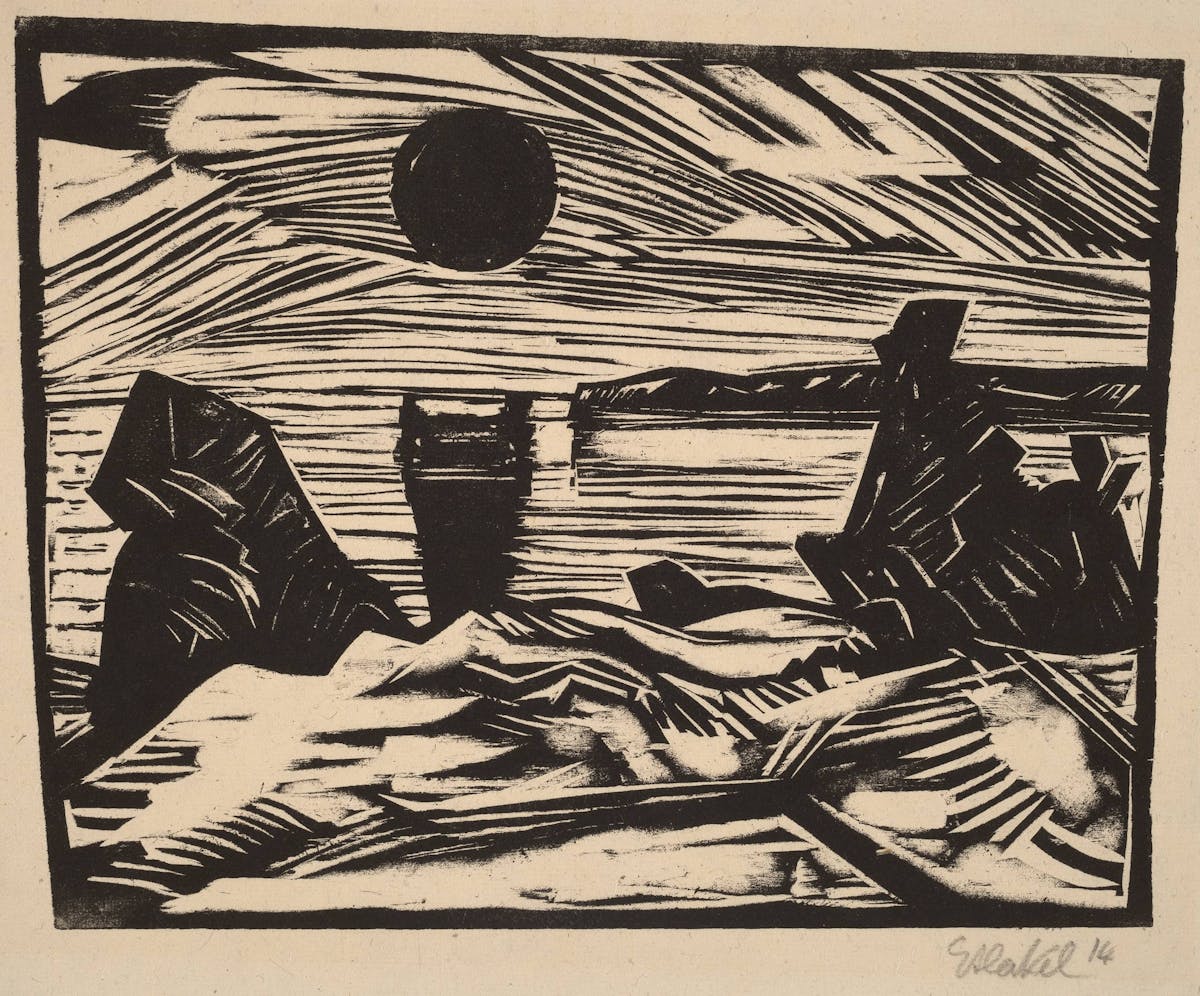

|The movement is embedded into our visual vernacular, particularly in our collective understanding of horror, pain, isolation and anxiety.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By THE NEW YORK SUN

|

By JOSEPH CURL

|

By LAWRENCE KUDLOW

|

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|

By MATTHEW RICE

|

By LUKE FUNK

|

By BENNY AVNI

|

By JOSEPH CURL

|