George Condo, Known for His Impertinent and Cheeky Deconstructions of Modernism, Proves Staunchly Resistant to Depth

Condo has long been adept at taking the visual vocabulary of high modernism and straining them, violently or hilariously, through a contemporary lens.

‘George Condo – Pastels’

Sprüth Magers Gallery, 22 East 80th Street, 2nd Floor, New York, NY

Through March 1, 2025

Hauser & Wirth, 134 Wooster Street, New York, NY

Through April 12, 2025

George Condo’s double opening at the uptown Sprüth Magers Gallery and the SoHo location of Hauser & Wirth establishes him as a known, if not always celebrated, quantity in the contemporary art world. Known for his impertinent and cheeky deconstructions of modernism, a cubist portraiture referred to in some corners as “cutism,” he now occupies both galleries with large, handsome pastels.

It doesn’t take more than a glance to recognize a Condo. He has long been adept at taking the visual vocabulary of high modernism — Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Klee et al — and straining them, violently or hilariously, through a contemporary lens. The results are always visually adept and eye catching. They are also so practiced as to nearly be slick.

Mr. Condo has been doing this routine and selling it briskly for more than three decades now. He’s found a way to explode modernism as a visual joke, and this is the joke that is continuously on display.

Mr. Condo is largely known for his portraits of imaginary subjects taken apart and involuted to such extremes they often border on abstraction. Yet they manage to insistently maintain their own, albeit anxiety-saturated, presence. The pieces at Sprüth Magers are largely imposing affairs that carry on the Condo tradition of exploded heads and faces.

“Mask” for example, features a bright turquoise pseudopodal eye. The other eye, green, is extended on a grey amorphous trunk. There are geometric shards between and beneath them that arrange themselves into a cubist bouquet of lavender and ochre, powder blue and brick red. A row of teeth, possibly attached to a jaw, protrudes to the side.

Mr. Condo relies heavily on the human eye’s well-trained tendencies to unify and anthropomorphize. That his scrambled twists of abstraction read as faces at all is, in fact, a bit of a marvel. “Frantic Circus Figure” and “Red Spatial Figure” both have this pleasing disjuncture between kinetic imbalance and judiciously placed pictorial and geometric elements. Mr. Condo knows how to smartly arrange a visual space, and the eye always has places to travel.

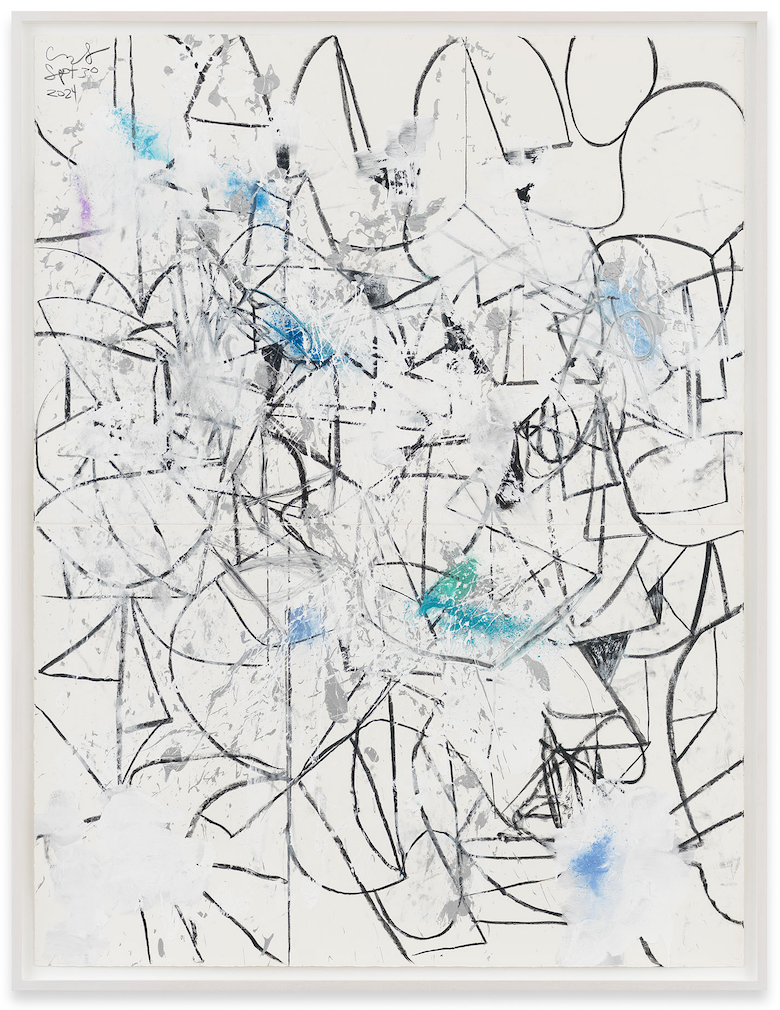

He’s a bit better when he addresses a purer abstraction, as he does in two of the Sprüth Mager paintings. Take “Chaotic Combustion,” which appears to be riffing off Picasso’s famed black and white abstraction “The Kitchen,” or one of Paul Klee’s seductively spare drawings.

Mr. Condo takes the serene musical composition of its inspiration and rattles it towards the bottom, as if he took the original and shook it a bit. There are pleasing traces of cadmium yellow and powder blue added to the broken lines. Mr. Condo is a very competent colorist, and he has a talent for finding the breaking point between harmony and anarchy.

You just have to ask yourself if it’s too much of the same. Mr. Condo’s long-standing modernist mash-ups are not highbrow, lowbrow, or even middlebrow, but unibrow, a weirdly consistent uniformity that belies a surface evenness. Hugely skillful, but staunchly resistant to depth.

The 12 large pastels that grace the enormous space of Wirth’s Wooster Street address radiate this sameness. Inventive, sure, and well-rehearsed, but haven’t we seen it before?

Other critics tend to speak about Mr. Condo in purely formalistic terms, because formalism seems to be the thing he is arguing with, if not outright lampooning and skewering. Mr. Condo has a longstanding beef with modernism. Watching him trot out his tricks is almost like watching him try to fight his way out of a wet paper bag.

As for the talk about the “psychological states” that Mr. Condo addresses in his subjects. They are imaginary, so what states, exactly? If anything, they radiate an anxiety of being trapped in a pleasing but ultimately sterile cul-de-sac.

Mr. Condo is fastidiously clever, and visually he is preternaturally astute. His main emotional component, however, appears to be snark. For me Mr. Condo’s work has always operated on a current of impish, if not perverse, humor bordering on nastiness.

He carries on his work very cheerfully and successfully, but there is an undercurrent of despair. Could it reflect the angst that comes about from being trapped in the end of art history, doomed to repeat its machinations with no end in sight?