Long Buried in a Closet, Early Jazz Treasures Emerge

Luis Russell is probably best remembered as a key collaborator to two extraordinary trumpeter-singers of New Orleans, Louis Armstrong and Henry ‘Red’ Allen.

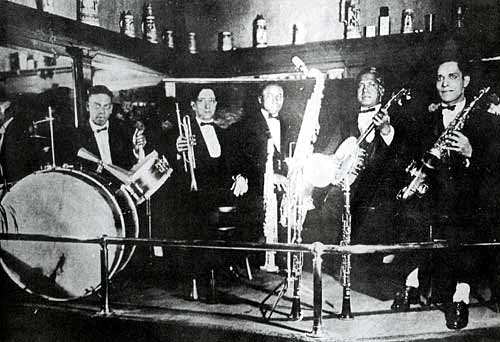

Luis Russell

‘At The Swing Cats’ Ball: Newly Discovered Recordings From The Closet’

Dot-Time Records

In 1953, the great bassist and composer Oscar Pettiford recorded an original tune he titled “Blues in the Closet.” That number has nothing to do with this new Luis Russell release except in the most literal sense: This is a private stash of blues and jazz that was actually in a closet for 85 years.

Pianist and bandleader Russell was born in Panama in 1902 and died in New York in 1963. In between, he grew up and came of age musically in New Orleans, and thus was a part of the all-important flowering of jazz in the Crescent City and then the subsequent diaspora.

Russell is probably best remembered as a key collaborator to two extraordinary trumpeter-singers of New Orleans, Louis Armstrong and Henry “Red” Allen. In recent decades, he’s also known as the founder of a miniature musical dynasty that extends to his wife, Carline Ray (1924-2013), a bassist and pioneering female instrumentalist, and their daughter, Catherine Russell, one of the finest blues-and-jazz vocalists of the 21st century.

Russell recorded roughly three-dozen classic sides in the late 1920s and early ’30s. For most of the late 1930s, he served as musical director for Armstrong, and even though he also continued to play gigs on his own he wasn’t making commercial records at this point. Russell was performing on the radio, though, and had some “airchecks” taken down from live performances at his own expense.

More recently, Catherine Russell unearthed a stack of these live broadcast recordings, and, working with her jazz scholar husband, Paul Kahn, and an audio restoration specialist, Doug Pomeroy, is now releasing them through Dot-Time Records.

This 50-minute disc is worth the price of admission just for the first half, which is all previously unknown performances by Armstrong fronting the Russell band in 1938. The acetates capture Armstrong on jazz standards such as “After You’ve Gone” and “Them There Eyes.” There are also fragments of a novelty riff number, “Mr. Ghost Goes to Town”; alas, Armstrong’s vocal is missing, but we hear the clarinets phrasing in suitably ghostly fashion.

The most interesting piece is Chappie Willet’s “Blue Rhythm Fantasy,” a wild, extended “flag waver” of a swing dance number, ironically featuring the whole band except the frontman. It’s a rather tantalizing example of what the Russell band was up to in this otherwise-undocumented moment.

Then there’s a mini-set of remarkable numbers by the Russell orchestra on its own, which, it’s good to say, were captured by some superior recording technique, as the audio quality here is fantastic. A few numbers feature a vocalist named Sonny Woods who seems to be trying to combine the flamboyant showmanship of Cab Calloway with the high style of the concert baritones of the era. Better, there are two brief but wild, near ecstatically uptempo numbers that further illustrate how solid this otherwise unrecorded orchestra was at the time, “Algier’s Stomp” and “Hot Bricks.”

Two vocal numbers stand out: First, the under-appreciated Midge Williams does a remarkable job of recreating the Boswell Sisters arrangement of “Heebie Jeebies” but as a solo number. Then there’s the premiere of “At The Swing Cats Ball,” a Russell original that, soon in the hands of Louis Jordan, would foreshadow the beginnings of what later became known as rhythm-and-blues. The band and the singers swing mightily on these — we only wish we had several more CDs of these tracks in this sound quality.

The disc ends with some very private performances from 1940, in which Russell tries out his chops as a solo stride pianist. He offers renditions of three pieces by Willie “the Lion” Smith, including the impressionistic “Echo of Spring.” The disc ends with a brief run through of “Ripples of the Nile” composed by Luckey Roberts in 1912 — and which later became the basis of a Glenn Miller hit, “Moonlight Cocktail.”

Catherine Russell and Paul Kahn have promised to share other buried treasures from the family closet; if they’re as good as what we’re hearing here, I can’t wait. These are amazing examples of what great musicians can do in moments when history isn’t looking.