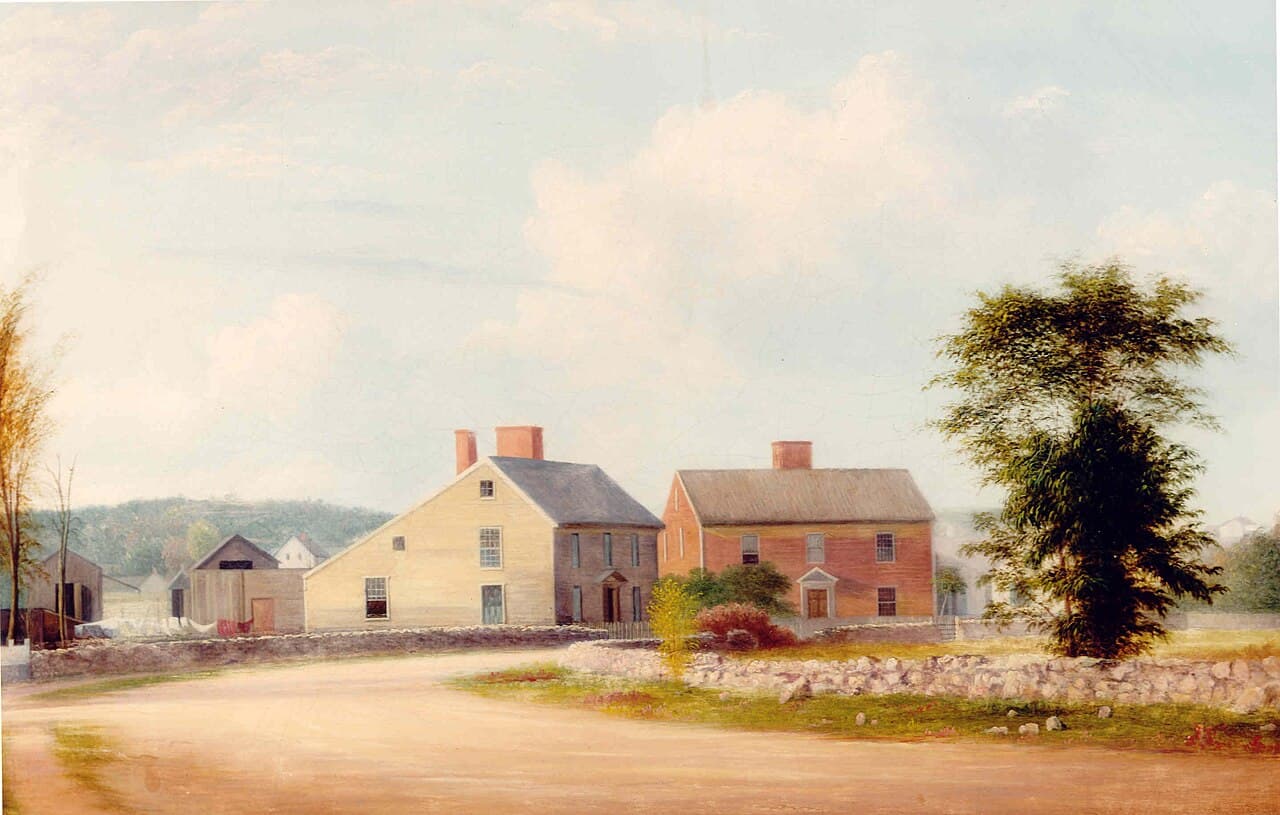

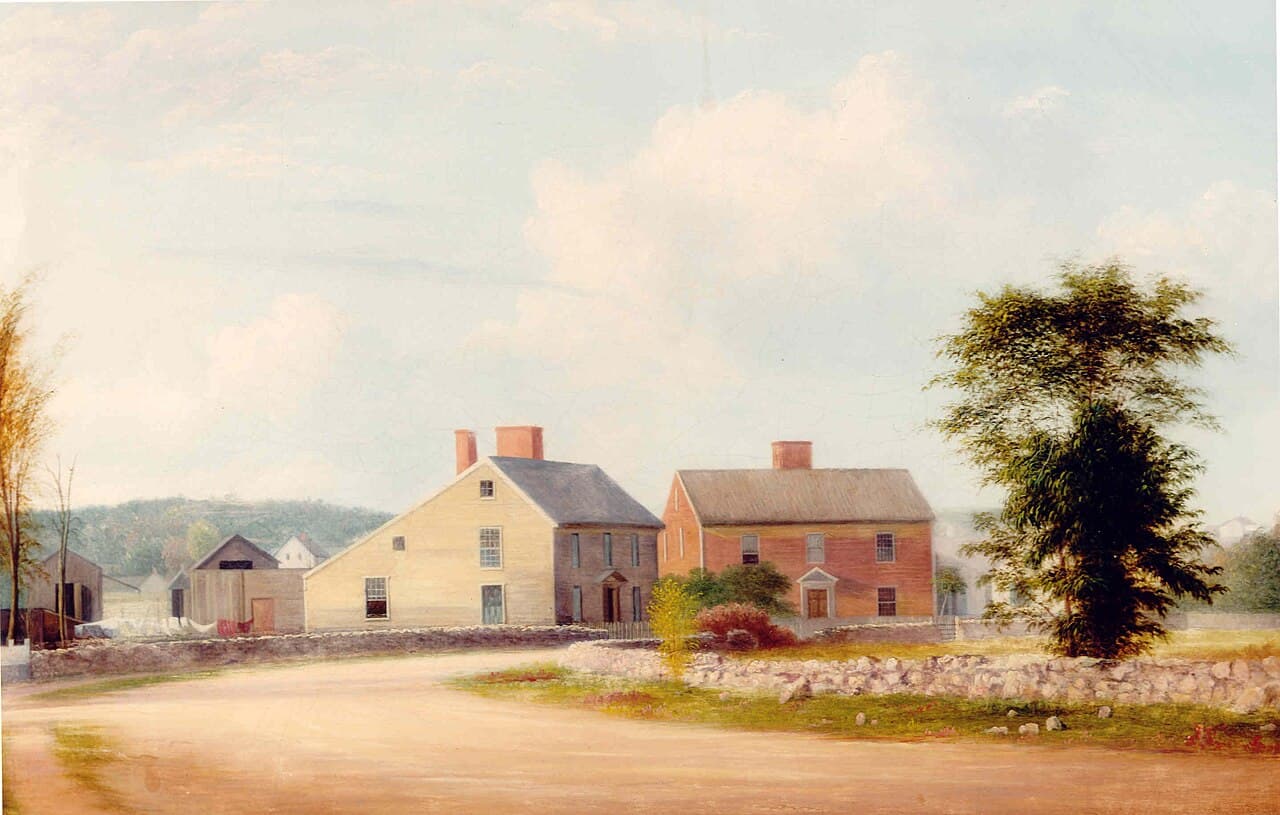

From Log Cabins and Empty Lots, Presidential Origins Manifest America’s Destiny

By DEAN KARAYANIS

|This set proves that there are no lesser periods in the career of an artist of her stature. She sings so quietly and subtly that, as Truman Capote wrote, a bee could lie sleeping in the palm of her hand and never wake up.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By DEAN KARAYANIS

|

By CONRAD BLACK

|

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By JOTAM CONFINO