Hamas, Defying Trump, Eyes Keeping Control of Gaza

By THE NEW YORK SUN

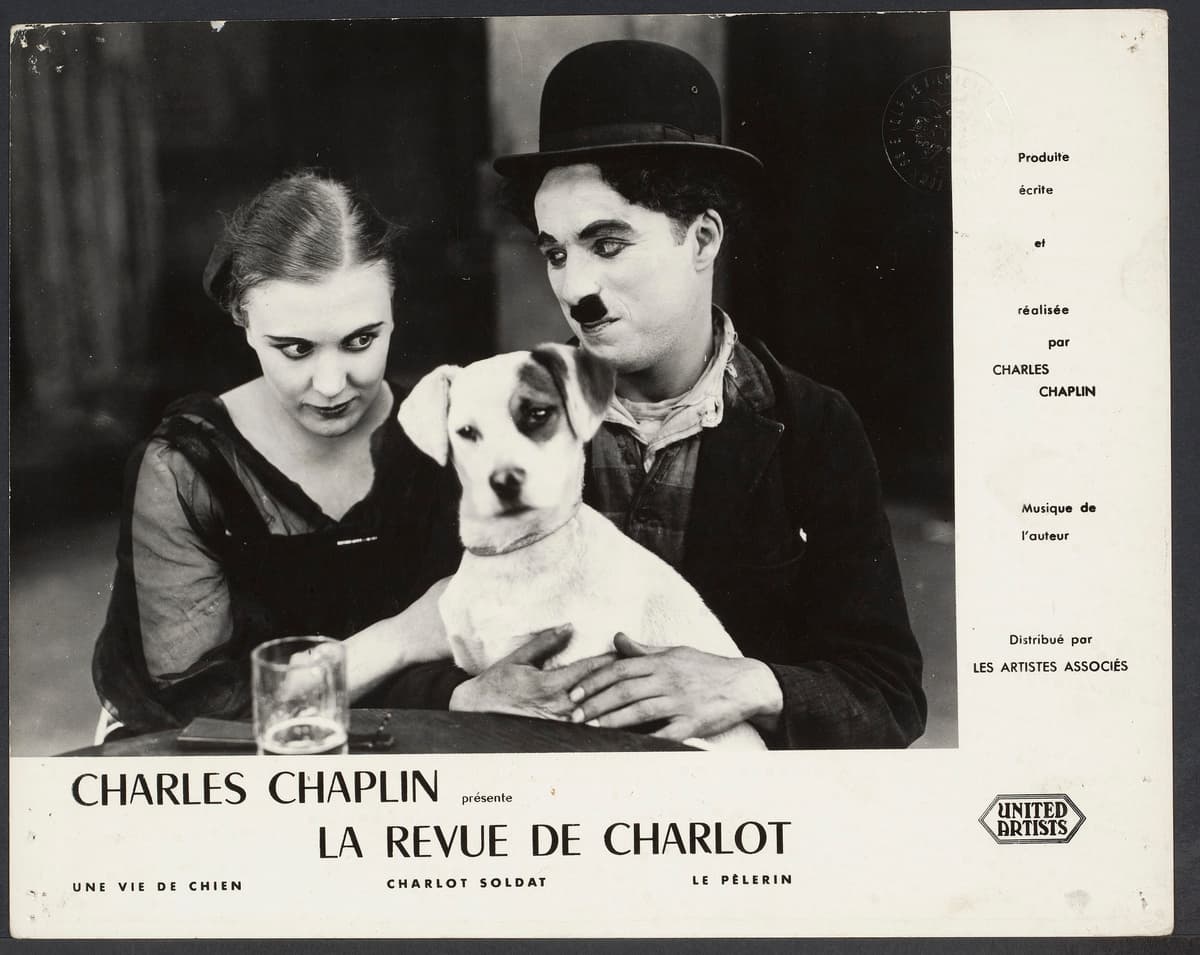

|Gen Zers, in particular, avoid silent movies not so much because they feel them antiquated or boring, but because they engender anxiety. The level of attention required can be too much to ask.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By THE NEW YORK SUN

|

By CAROLINE McCAUGHEY

|

By JOSEPH CURL

|

By MATTHEW RICE

|

By LUKE FUNK

|

By JOTAM CONFINO

|

By NOVI ZHUKOVSKY

|

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|