Not Even the Avant-Garde Could Escape the Base Realities of Covid

As the Public Theater’s Under the Radar Festival makes its in-person return, a focus on the challenges and necessity of communication.

What if mankind could reverse all the damage and destruction it has wrought? What insights might lie hidden within the belly of a whale? How much can a group of strangers learn about each other in the course of 70 minutes, most of them spent taking turns reading from a stack of index cards?

These are but a few of the questions raised in the Public Theater’s 18th annual Under the Radar Festival, a 19-day celebration of the avant-garde that runs through January 22. Featuring 36 artists from across the country and spots as far flung as Australia and Venezuela, this year’s lineup offers a predictably wide array of cultural influences, from the Kardashians to Mary Shelley, “Moby Dick,” and the ancient Mesopotamian “Epic of Gilgamesh.”

Based on an early sampling, at least, this year’s lineup is also addressing concerns that have become more pronounced since the festival was last presented in person, in 2020, shortly before the Covid shutdown began. (Due to a spike in cases, the 2022 festival was canceled after it had been announced.) The queries listed at the start of this article arise from three works that deal, in different ways, with the challenges and necessity of communication — something we’ve all had time and reason to reflect on over the past three years.

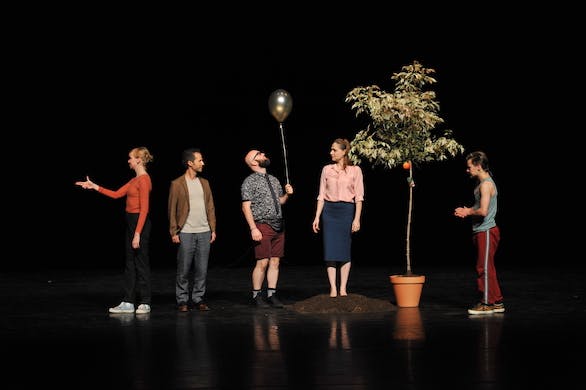

Environmental distress is also explored in all three, most graphically and fancifully in “Are we not drawn onward to new erA,” being performed by the Belgian theater collective Ontroerend Goed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Alexander Devriendt directs a company of six actors, who at first assemble on a stage occupied only by a small tree bearing a single red apple. If you’re sniffing biblical imagery, you’re on the right track, though the spare dialogue that pocks the extended silences offers few clues; it’s spoken in a seemingly nonsensical language that at first may suggest some alien species filling in for Adam and Eve and, well, the others.

Only after Philip Aguirre’s set design has become busier, with colorful plastic bags raining down and a huge statue materializing in parts that are fit together with much grunting and fuss, do the characters’ thoughts and intentions become clear, in accented English. The live recording that allows for that process, in conjunction with Jeroen Wuyts and Seppe Brouckaert’s lush video design and William Basinski’s mournful music, lend a fetching lyricism to the second half of the production, which elucidates the first in ways that are playful and poignant — even if the whole affair, which runs just over an hour, feels longer than it should.

“The Indigo Room,” by the “ritualist” Timothy White Eagle and his collaborators, known as The Violet Triangle, makes its case for healing the planet and its people in a more immersive fashion. Upon arrival at La MaMa’s Ellen Stewart Theatre, audience members collect cards directing them to games in a carnival room. One is a live variation on the battery-operated classic “Operation,” with a wisecracking actor’s head poking out from under a cardboard drawing of a pirate; another involves throwing Barbie dolls at a dart board.

Before entering the larger space in which Mr. White Eagle holds court, attendees listen to a sermon — delivered in mock-preacher style by Paul Budraitis, with whom he co-created the piece — that promotes courage and hope, but includes a fable about a charming, clever stranger who preys on those qualities. Mr. White Eagle, a noted Indigenous artist who advised Taylor Mac on the landmark performance piece “A 24-Decade History of Popular Music,” proves a warmer presence, but he opens his portion just as ominously, with a tale about a beast with an insatiable appetite.

This is the Swallowing Monster, a creature rooted in early mythology, holds “deep resonance for modern people as we consider our current all-powerful macrosystems of capitalism, military-industrial complex and corporate-led politics,” as Mr. White Eagle explains on his official site. Onstage, Mr. White Eagle, who is also the production designer, is more interested in ritual than preaching; for the central part of the show’s journey — through the belly of that whale — he relies on sounds and simple imagery as much as words, chanting, and drawing with chalk under Nic Vincent’s evocative lighting.

Mr. White Eagle can also be an engaging storyteller, particularly when he’s recounting personal experience. I was a little thrown when he shifted suddenly from a memory of nearly drowning as a boy to one of asking his lover to take his shirt off while making pasta, but in the end, his accounts all fed a reassuring, if not quite original, message: that pain and joy are equally inevitable, as much as are life and death.

“A Thousand Ways (Part Three): An Assembly” offers even more of an interactive experience, with the audience essentially performing the piece. It’s the third and final installment in a series by the Obie Award-winning duo of Abigail Browde and Michael Silverstone, whose mission statement declares they’re “aiming at a radical approach to making live art by creating intimacy amongst strangers and illuminating the inherent poignancy of people coming together.”

Here, that entails gathering about 16 people in a room at the New York Public Library’s Main Branch on Fifth Avenue, and handing them a hefty set of index cards containing lines and instructions. The idea, presumably, is that everyone will take turns reading aloud, though there’s no pressure to do so. (I chickened out, I’ll confess.) Attendees are expected — or encouraged, at least — to answer a bunch of mostly yes-or-no questions, some fairly personal, though not gratuitously or distastefully so. References to dirt and dust are sprinkled in, presumably to remind us of our shared vulnerability as earth-dwellers regardless of whether we have children, or are looking for love, or have had an organ removed.

Frankly, on the occasion I took part, I found “A Thousand Ways” less intriguing for its text than for the responses it elicited from some of the more generous or extroverted participants. Perhaps that’s the point: that a sense of community can spark the creative juices in all of us. After a period marked by both isolation and conflict, it’s at least a nice thought.