An American Hostage the Taliban Won’t Admit Exists

By HOLLIE McKAY

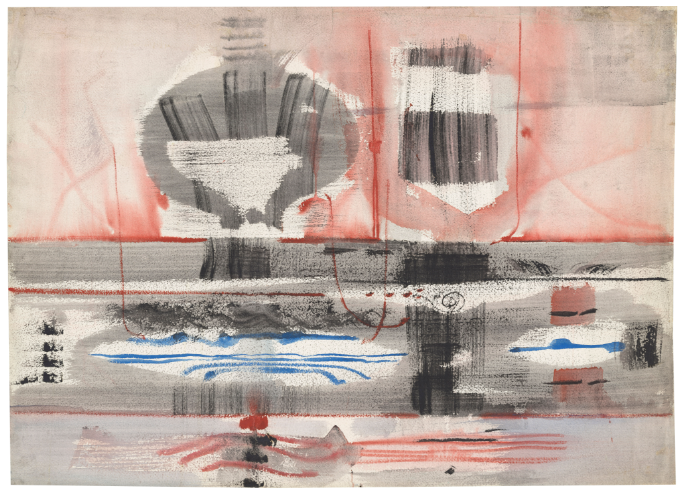

|This is your chance to see Rothko’s paintings on paper as he intended them — many of them are exhibited without the protective intercession of museum glass between your eyes and his paint.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

By HOLLIE McKAY

|

By HOLLIE McKAY

|

By LAWRENCE KUDLOW

|

By HOLLIE McKAY

|

By JOSEPH CURL

|

By THE NEW YORK SUN

|

By A.R. HOFFMAN

|

By JOSEPH CURL

|