Will Friday Diplomacy With the Islamic Republic Lead to a Military Strike?

By BENNY AVNI

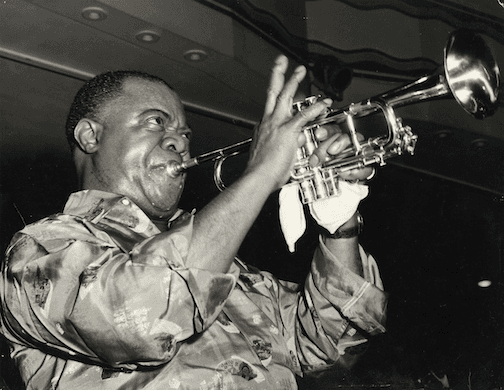

|‘Stomp Off, Let’s Go’ could easily be two volumes, which would bring to four the total of Ricky Riccardi’s series on one of the central figures of 20th century culture.

Already have a subscription? Sign in to continue reading

By BENNY AVNI

|

By BRADLEY CORTRIGHT

|

By CARLOS SOUSA

|$0.01/day for 60 days

Cancel anytime

By continuing you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.