Titanic Submarine Passengers Join Long List of Explorers Who Pushed the Limits … and Perished

A history of risking it all in service of exploration.

Risk is not made equally.

Some risk is flippant and comic — $10 on a racehorse or on two tech billionaires having a cage fight. Other risks are repulsively reckless. To hear stories of families left destitute by a husband’s gambling addiction is heartbreaking but also maddening.

And there’s the kind of risk that matters most: exploration. Astronauts at the edge of physics. Mountaineers beyond the end maps. Divers looking into the black abyss where no person had gone before.

For the last several days, the world’s eyes have been focused on the Titan submersible, which went down to look at the wreck of the RMS Titanic, only to join it. Aboard it was the designer, whose cost-cutting seems to have cost the lives of four other people, including a nineteen-year-old, who just sought a taste of adventure.

It’s a tragic story, but our collective interest serves to remind us how much we value exploration and the risks involved. And so, it’s worth looking back on those other explorers we have lost, who either vanished beyond the outlines of our maps or died in their quests into the unknown.

David Livingstone (1813 – 1873)

A hero of Victorian Britain, son of the Scottish working classes, devout missionary, and passionate abolitionist, Livingstone sought to find the elusive sources of the Nile River and mapped much of central and southern Africa in the process. He would never find that famous font, but his journey was motivated by a higher purpose: not simply spreading Christianity and trade to Africa, but to attain such fame that he could sway his home country, and make it more civilized, through the abolition of the Arab Slave Trade, which he strongly opposed.

In 1866 he would return to Africa, but his following journey — setting off from Zanzibar — was plagued by desertion, theft, and ill-health, and would ultimately end him. Livingstone’s death was first of spirit, then body. In his diary, dated July 15, 1871, he recounts having witnessed Arab slavers massacre 400 Africans at the Nyangwe market by the Lualaba River in present-day Congo. The act shook him so thoroughly that he would abandon his search for the origins of the Nile. He trekked back to the village of Chipundu in the present-day Zambia and died two years later, on May 1, 1873.

Henry Hudson (1565 – 1611)

Henry Hudson is among history’s most influential explorers, having mapped Canada and northeastern America, and thus played a crucial part in the European settlement of the “New World.” And yet, we know little about the man himself. What we do know is that, when searching for the Northwest Passage on the Discovery during his final expedition, he and his crew wintered at James Bay.

With the ice clearing, Hudson wanted to push on but — according to the ship’s navigator, Abacuk Pricket — most of his crew refused, mutinying. They left Hudson, his son, and six crew members adrift on a small open boat, never to be heard from again — but his name lives on in the Hudson Strait, the Hudson Bay, and anyone who calls America home.

John Franklin (1786 – 1843)

Where Livingstone inspired much of his home country, sent by moral purpose and embodying a hero’s journey, Franklin’s was closer to tragedy, as his Arctic exploration ended in brutal tragedy and shook Victorian society. His merchant father had tried to persuade the young Franklin to be a clergyman or a businessman, but John was drawn to the ocean and had his first trial voyage at age 12. After serving in the Napoleonic Wars and War of 1812, he would mount three expeditions into the Arctic, the last of which, seeking to chart the Northwest Passage, departed in 1845.

A large search and rescue mission would follow in the years after, hoping to find HMS Terror, HMS Erebus, and their 129 crew members. In 1854, the Scottish explorer, John Rae, would learn of their fate from the local Inuit hunters. The ships had become icebound in 1847, and the crew succumbed to starvation and cold and ultimately resorted to cannibalism. In 1997, analysis of bone remains would verify Rae’s report. Despite his horrific end, Franklin’s exploration was enormously important for mapping the Arctic.

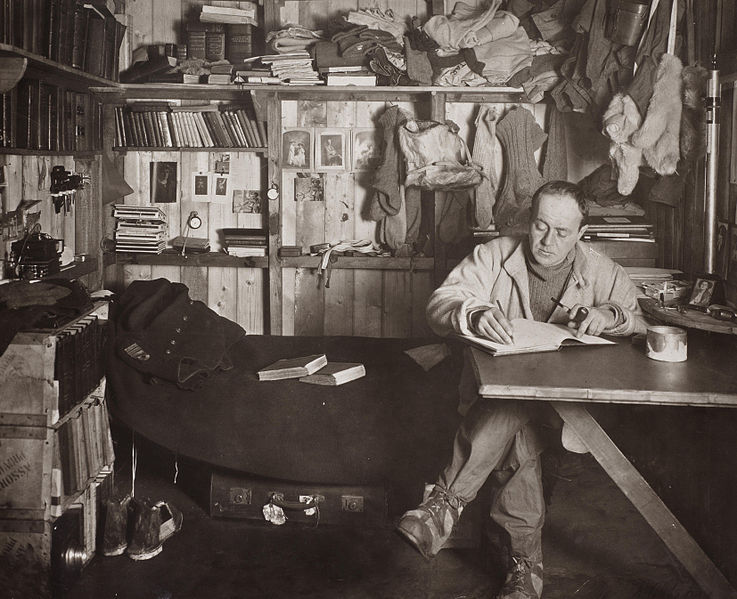

Robert Falcon Scott (1868 – 1912)

A British Royal Navy officer and Antarctic explorer, Scott was among the first to reach the South Pole, arriving on January 17, 1912 — but five weeks after Roald Amundsen’s expedition. However disappointing, the return of his Terra Nova expedition — which he feared, in his diary, would be “dreadfully tiring and monotonous” — proved to be far worse, as poor planning, bad weather, and worse luck led to his death and all of his party.

Though his final diary entries ring with morality and noble purpose — “Last entry. For God’s sake look after our people” — his reputation would become muddied with time, with historians in the mid-20th century decrying him as a “heroic bungler,” and more contemporary historians putting focus on the weather. His legend is bound to the moment’s view of the British Empire, for whom he was a symbol — at one point loved, later hated, and now perhaps reconsidered.

George Mallory (1886 – 1924)

Mallory, an English mountaineer, was part of the first three British expeditions to Mount Everest, and perhaps has the quote that best encapsulates the spirit of adventure. After his second journey, in 1922, breaking the record for the world’s highest climb, a reporter asked why he climbed Everest. His answer: “Because it’s there”

Two years later, the mountain would claim him as he and his climbing partner, Andrew Irvine, disappeared over the Northeast Ridge — all but 800 feet below the summit. His body was finally discovered 75 years later by the 1999 Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition, and it remains unknown whether the two men had reached the summit. If they had, they were the first to do so, some 29 years before Edmund Hillary.

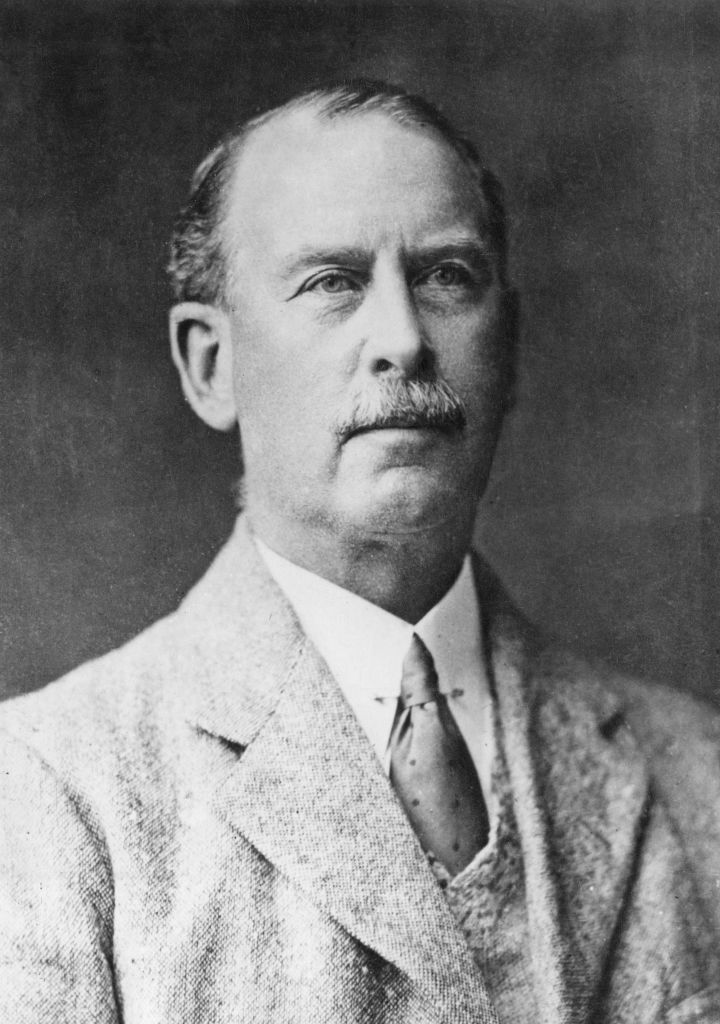

Percy Fawcett (1867 – 1925)

Among the most famous of vanished explorers, Percy Fawcett — along with his eldest son, Jack, and his friend, Raleigh Rimell — traveled deep into Brazil, hoping to find the mythical “Lost City of Z,” believed to be situated in the Amazon rainforest. He had spent the years 1906 to 1914 mapping much of Brazil and Bolivia, before returning to Britain to serve in World War I, but “Z” became a fascination to him, and after a failed solo expedition in 1920, he would set off on his final journey on April 20, 1925.

His last message was sent to his wife on May 29, and the three men vanished into the unknown. His journey became the topic of David Grann’s 2009 bestselling book, “The Lost City of Z,” which was then adapted in 2016 by auteur filmmaker, James Gray, into a film starring Charlie Hunnam and “Spider-Man” star, Tom Holland.

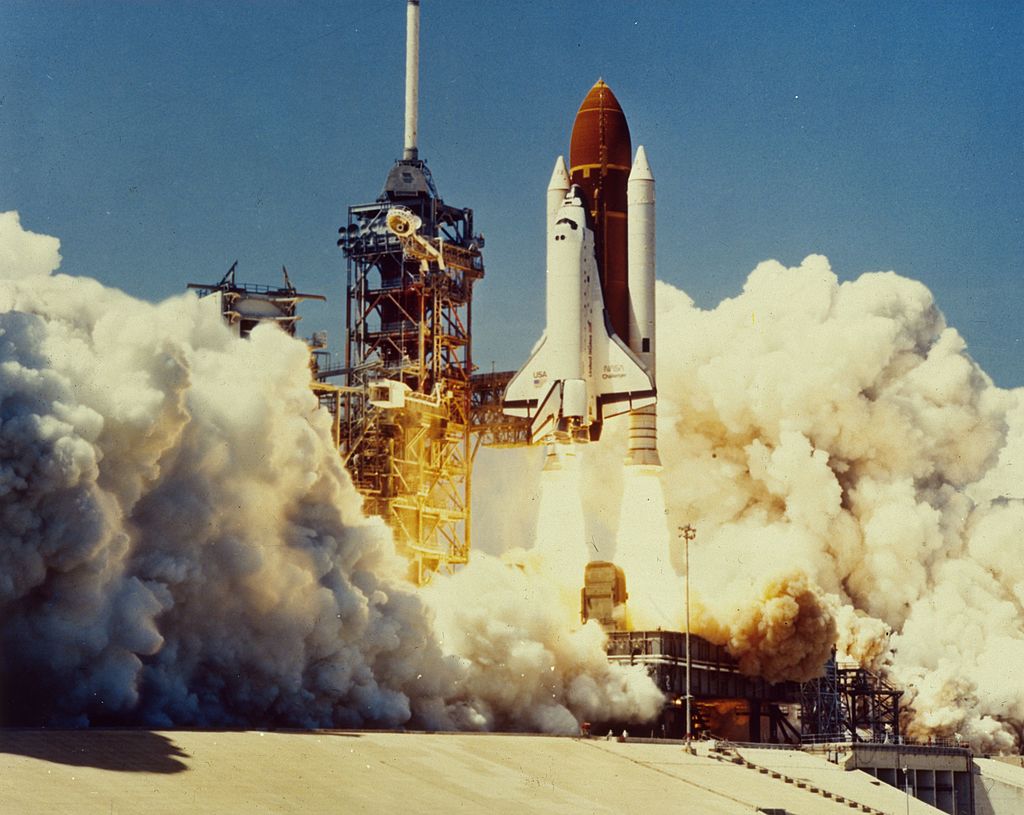

Challenger Disaster (1986)

Having mapped the globe and reached every mountain peak, the mid-20th century saw the spirit of exploration turn to that black infinite. To get man into space remains an immense challenge, and the space race brought America to the edge of technical innovation and human bravery. As depicted in Damien Chazelle’s 2018 masterpiece, “First Man,” each launch was the equivalent of welding people to a bomb and firing them into the atmosphere. Eventually, the bomb goes off.

That happened on the 25th Space Shuttle launch, on January 28, 1986, when the Challenger tore apart but 73 seconds after takeoff, as the O-ring seals in the shuttle’s right rocket booster failed. All seven crew members were killed.

In the aftermath, President Reagan created the Rogers Commission to investigate the accident, and ultimately, despite the difficulties of space, it proved to be very mundane, bureaucratic communication issues that had led to the disaster. Seal leakages had become acceptable at NASA, so long as the flight was successful, and NASA’s management had reported the risk of an explosion was only one in 100,000. Engineers, on the other hand, had put it a thousand times higher, at a worrying 1 percent.

Richard Feynman ends his addendum to the commission’s final report by writing: “For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled.”

It’s a message that rings all the truer today.

1996 Everest Disaster

Everest’s appeal has always, in part, been in its lethal risk. Even so, the 1996 season changed the public’s attitude towards the mountain, as between May 10 and 11, eight people died on its slopes, seemingly because of a rivalry between the leaders of two different climbing teams, who ignored avalanche risks to their peril. Four of the “Adventure Consultants” team died, including its leader, Rob Hall; the leader of the competing “Mountain Madness” team, Scott Fischer, also died; and the final three casualties were police officers of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police.

This story was brought to particular attention through Jon Krakauer’s best-selling 1997 book, “Into Thin Air,” which recounted his experience as a survivor of the “Adventure Consultants” team. This later became the focus of the 2015 film “Everest.” Hall’s wedding ring was brought back for his widow, but on her request, he was left on the mountain, “where he’d liked to have stayed.” The bodies of Doug Hansen and Andy Harris were never recovered.